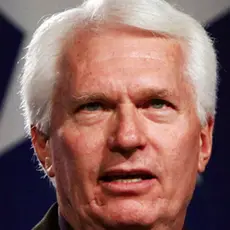

Saturday morning’s speech by Bryan Fischer of the American Family Association may be the most valuable moment of this conference. It’s not often that Americans get an unambiguous look at the Religious Right’s extremely dangerous definition of religious liberty.

Religious liberty is of course a core American value, protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution. And it’s the separation of church and state that protects the right of every American to worship or not as they choose, and protects all Americans from the government using its power to coerce religious belief or worship. It’s one of the constitutional principles that define this country.

Fischer basically attributed the idea of church-state separation to Adolf Hitler, who he said was the inspiration for the forces of “secular fundamentalism” who are bent on “castrating” the church and bringing America a “bleak, dark, vicious, tyrannical” future. Invoking Hitler is practically commonplace name-calling from the right these days. But it was not the most important or provocative point of his remarks.

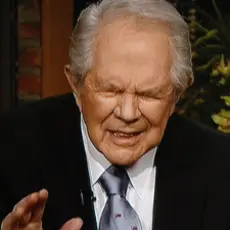

Today Fischer went a good bit further than televangelist Pat Robertson, who notably called church-state separation a “lie of the left.” According to Fischer’s interpretation of the First Amendment, here’s what religious liberty means: Congress has the liberty to promote religion in any way, as long as it does not single out one Christian sect or denomination and make it the nation’s official religion. That’s it.

According to Fischer, “the only entity that is restrained by the First Amendment is the Congress of the United States.” Thus, he says, it is “constitutionally impossible” for governors, mayors, city councilmembers, or school administrators to violate the First Amendment. Fischer said the “incorporation doctrine” – the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment applied First Amendment protections against state governments, is the “most egregious” example of judicial activism.

So by his definition, a state legislature could declare itself an officially Christian state. Or an officially Baptist or Mormon state. Presumably any public school, city council or state government could require students to attend Christian worship or profess certain religious belief.

Fischer isn’t the only Religious Right leader who holds this radically extreme definition of religious liberty. In their 2008 book, “Personal Faith, Public Policy,” Religious Right leaders Tony Perkins and Harry Jackson said that a 1961 Supreme Court decision, which held that the state of Maryland could not require applicants for public office to swear that they believe in the existence of God, one of “the major assaults that have been successfully launched against the Christian faith in the last forty to fifty years.”

So, to these prominent Religious Right leaders, preventing a state from demanding that its employees swear to certain religious beliefs is an attack on Christianity. And any court that tries to stop a state from imposing religious beliefs on its citizens is judicial activism.

It’s disturbing to note that Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is among those who believe the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment does not apply to the states. In a 2004 concurring opinion, Thomas wrote:

Quite simply, the Establishment Clause is best understood as a federalism provision — it protects state establishments from federal interference but does not protect any individual rights. . . . .

[E]ven assuming that the Establishment Clause precludes the Federal Government from establishing a national religion, it does not follow that the Clause created or protects any individual right. . . . it is more likely that States and only States were the direct beneficiaries. Moreover, incorporation of this putative individual right leads to a particular outcome: It would prohibit precisely what the Establishment Clause was intended to protect — state establishments of religion.

Americans deserve to know whether the parade of top GOP officials who engaged in this weekend’s mutual love-fest with Religious Right leaders have the same narrow, distorted view of the First Amendment.