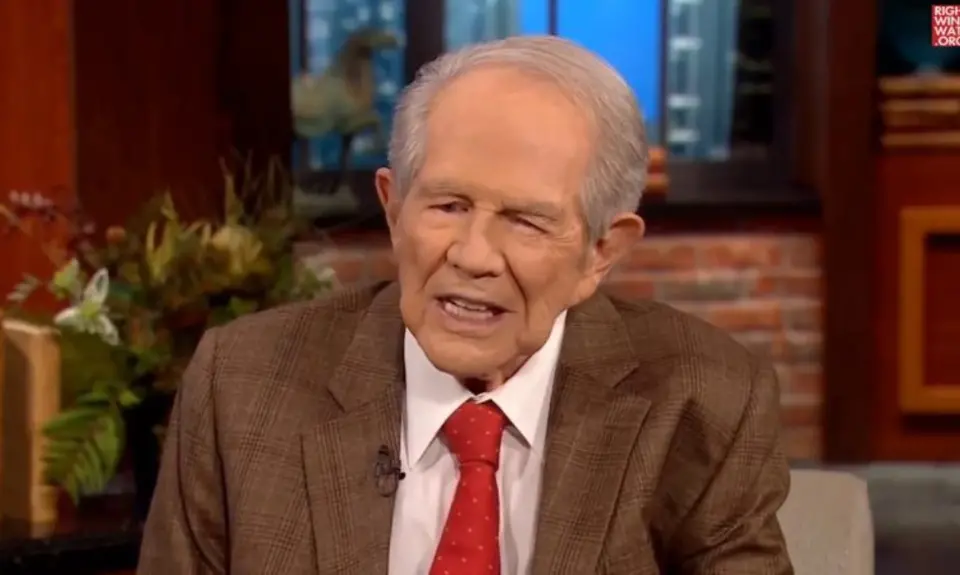

Pat Robertson, who was a central player in religious-right broadcasting and politics for decades, died on Thursday. As People For the American Way President Svante Myrick noted, “Pat Robertson was a key figure in the rise of the authoritarian religious-right political movement. He helped build the movement’s massive media, legal, and political infrastructure, which today is pushing harmful attacks on the freedom to learn, LGBTQ equality, reproductive choice, church-state separation and more.”

Robertson was a pioneer and longtime force in Christian broadcasting. His 700 Club television show went on the air in 1963, and long after Robertson was no longer a personal force in right-wing politics, the show gave him a platform for promoting bigotry, conspiracy theories, and right-wing politicians, up to and including Donald Trump. (He stepped down from hosting in 2021 but continued to provide occasional commentary.)

Robertson was part of a crop of televangelists recruited by right-wing political operative Paul Weyrich in the 1970s to get conservative white evangelicals more involved in politics in opposition to federal challenges to Christian schools with racist policies and in support of anti-choice and anti-LGBTQ campaigns and hard-right candidates. Robertson started to dedicate a portion of his 700 Club show to right-wing politics in the 1980s.

People For the American Way, Right Wing Watch’s parent organization, was founded by television producer Norman Lear and other prominent Americans, including the late Rep. Barbara Jordan, as a response to the divisive rhetoric and harmful agendas of newly politicized televangelists like Robertson. After People For had successfully used the since-abandoned Fairness Doctrine to get time on television stations to respond to Robertson’s political diatribes, Robertson wrote to Lear warning him against interfering with a “prophet” and telling him his arms were “too short to box with God.”

Robertson ran for the presidency in 1988, and while he didn’t win over enough voters to make much of an electoral impact, he built a big mailing list of supporters. After the election, he hired a young right-wing political operative named Ralph Reed to turn that mailing list into a political organization they called the Christian Coalition.

Reed and Robertson set an ambitious goal for the Christian Coalition: to take working control of the Republican Party over the coming decade from the ground up by recruiting activists to get involved in local party politics and get elected or appointed to positions from which they could shape the direction of the party and the candidates it backed. In coalition with other right-wing efforts, they were quite successful in making the Republican Party a reflection of the religious right movement and its political agenda.

The implosion of the Christian Coalition in the late 1990s, like the collapse of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority a decade earlier, was about organizational disfunction, not a sign of the religious right’s collapse. Indeed, the movement has over the past 40-plus years built a massive cultural and political infrastructure of colleges and universities, media outlets, advocacy groups, and electoral operations.

Robertson has an active legacy in every corner of the movement, including his Christian Broadcasting Network. “Love or hate Robertson, his reach is hard to ignore,” Christianity Today noted in its obituary of Robertson. “The 700 Club airs in 97 percent of TV markets in the U.S and is among the longest-running shows in history.”

Robertson founded Christian Broadcasting University in 1977, later renaming it Regent University, where he served as Chancellor. Through its undergraduate and graduate programs, it promotes its founder’s religious worldview. The law school absorbed Oral Roberts University’s law school, which former Rep. Michelle Bachmann had attended. Bachmann is currently dean of Regent’s Robertson School of Government, and has used it as a vehicle for promoting, among other things, false claims about the 2020 presidential election and Jan. 6 insurrection.

Robertson also founded the American Center for Law and Justice, launched in 1990, as his counterpoint to the ACLU, and it uses the courts to promote the religious-right agenda just like its bigger brother, the Alliance Defending Freedom.

In its heyday, the Christian Coalition hosted “Road to Victory,” then the largest annual political gathering of religious-right activists. When the Christian Coalition fell on hard times, the Family Research Council picked up the baton, hosting the Values Voter Summit for many years before recently renaming the gathering Pray Vote Stand. Ralph Reed, the political operative who built the Christian Coalition into a political force, made an unsuccessful run for public office before founding the Faith and Freedom Coalition, a voter-turnout operation which also hosts its own annual conference for right-wing activists called Road to Majority.

All these conferences have regularly drawn Republican elected officials, including members of Congress, governors, and, during the Trump administration, both Trump and his Vice President Mike Pence—a sign of the movement’s success in making conservative evangelical voters the most loyal and energized part of the Republican Party’s base.

Robertson also played an important role in making Charismatic Christianity more acceptable to traditional fundamentalists, a shift and political alliance that solidified in opposition to the election of Barack Obama and reached its zenith during the Trump administration, when Pentecostal dominionists gained unprecedented levels of access and influence.

Robertson’s longevity and his extremism made him a focus of Right Wing Watch’s monitoring for years; earlier today, we chronicled just a few of the hundreds of clips we gathered over the decades of documenting Robertson’s reactionary rhetoric.