This is a second in a series examining the backgrounds of the legal team defending President Donald Trump in his impeachment trial.

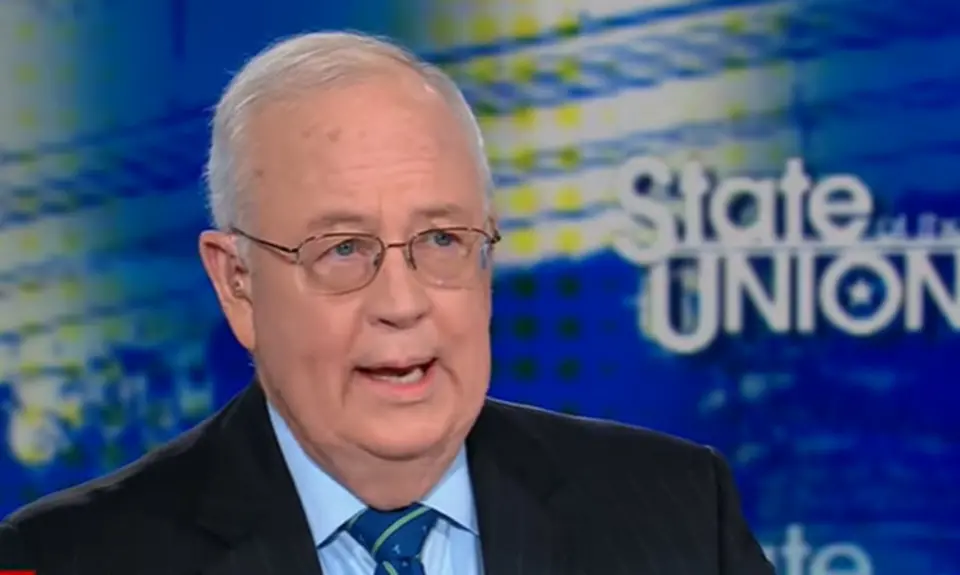

Kenneth Starr, a former federal judge, solicitor general, and special counsel who once nursed dreams of sitting on the U.S. Supreme Court, is now a member of the legal team defending President Donald Trump in his Senate impeachment trial. It's not Starr’s first cover-up. Starr helped notorious sex criminal Jeffrey Epstein negotiate a plea deal that barred future prosecutions of Epstein’s co-conspirators, and he was fired from his job as university president for failing to adequately address an epidemic of sexual assault on campus that involved members of the Baylor football team. "I think Ken Starr's role at Baylor was someone who didn't really know what was going on but should have," ESPN investigative reporter Paula Lavigne told CNN on Tuesday.

But the scandal that first put Starr's name on the lips of political pundits was Bill Clinton's sexual involvement with Monica Lewinsky, which ultimately led to Clinton's impeachment after he lied about it. Starr was named special prosecutor in the matter. According to journalist Al Hunt, Starr “calculated that nailing Clinton would enhance his chances for the Supreme Court under the next Republican president.” But instead, Starr’s Supreme Court prospects dimmed after the impeachment failed to remove Clinton, whose approval numbers actually climbed as Starr's team sought to further tarnish the president. Starr's investigation was widely seen as having gone off the rails, its most notable legacy being a prurient, quasi-pornographic report.

In 2018, Starr published “Contempt: A Memoir of the Clinton Investigation.” Writing about the “self-serving” memoir, Hunt declared, “Washington is full of self-righteous hypocrites — in both parties and of all persuasions. The king may be Ken Starr.” Starr told NPR’s Steve Inskeep that year that his investigation of Clinton was worth it because “no one is above the law,” adding, “what we’re really talking about ultimately is obstruction of justice and the abuse of power.” Now where have we heard those terms recently?

If Starr had any residual Supreme Court hopes, they were surely snuffed out when he was fired as Baylor University’s president in 2016 over the school’s failures in dealing with sexual assault allegations against members of the football team, which Starr had championed since becoming president in 2010.

In 2015, after an athlete was convicted of sexual assault, Starr called for an investigation. A report by the firm Pepper Hamilton concluded that “Baylor’s efforts to implement Title IX were slow, ad hoc, and hindered by a lack of institutional support and engagement by senior leadership.” Starr was stripped of his position as president after that scathing report, and a few months later, he resigned his remaining positions as chancellor and law professor.

The New York Times described Starr’s firing as punishment for “leading an administration that, according to a report by an outside law firm commissioned by the university’s governing board, looked the other way when Baylor football players were accused of sex crimes, and sometimes convicted of them.” Investigators said the university leadership “created a cultural perception that football was above the rules.”

Some victims and former officials, however, point directly at Starr. “Young women and several former officials said in interviews that Mr. Starr ignored the women’s cries for help and that he and other top officials at Baylor failed in their responsibility to shield the women from sexual harm,” the New York Times reported.

Court filings in a lawsuit against Baylor by a group of anonymous women cited a “light speed” investigation into a sexual harassment complaint that was closed in a day and criticized Starr’s support for a student who worked for him and was accused of sexual assault. Another woman suing the school accused school officials of “deliberate indifference” on the issue.

Starr has repeatedly described himself as having been unaware of the problem on campus before 2015. In 2019, he spoke at a conference on higher education law and policy and said that he had been responsible in the same way a CEO ultimately is responsible for what happens under their leadership, calling it “indirect responsibility, though not culpability.”

Starr has also been criticized for his role in securing what has been widely described as a sweetheart plea deal for the recently deceased serial sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Starr was part of Epstein’s legal team, which negotiated the deal with then-U.S. Attorney Alex Acosta, who had worked for Starr on the Clinton investigation. That agreement “shut down the F.B.I. investigation and gave immunity to all ‘potential co-conspirators’ — including any of Mr. Epstein’s rich and powerful buddies who may have taken a turn with his victims,” the New York Times editorial board noted last year. Last June, Acosta stepped down after two years as Trump’s Labor Secretary when public attention focused on the deal. Starr defended the plea deal last year.

Like Trump attorney Jay Sekulow, also on Trump’s impeachment defense team, Starr is aligned with conservative evangelicals who are Trump’s strongest supporters. While he was at Baylor, Starr delivered a keynote address at an event where Greg Abbott, then the state’s attorney general, was honored by a pastors' group led by a right-wing activist who denounced President Obama as an “enemy of Christianity” and gay people as “a morally depraved special interest group.”

NPR has chronicled Starr’s public redemption from disgrace to Trump’s legal team via, of course, Fox News, where he has been a regular in the network’s stable of Trump defenders.