The New Yorker is out with an excellent new piece by Jane Mayer that explores how Bryan Fischer came to be the bigoted firebrand known so well to readers of this blog. Over the years we’ve covered a seemingly endless stream of outrages by Fischer, who serves as American Family Association’s Director of Issue Analysis and host of “Focal Point” on AFA’s radio network. Yet Fischer only recently emerged on the national scene when he led the successful effort to oust an openly gay spokesman from the Romney campaign.

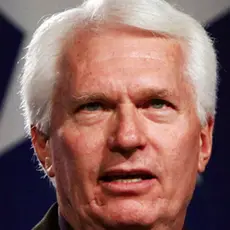

The New Yorker profile, appropriately titled “Bully Pulpit,” is Fischer’s first national media close-up, and the results are none too pretty. Mayer spoke with former and current friends and co-workers of Fischer, and the portrait that consistently emerges is of an extreme and rigid man who consistently drives friends away and is compensating, to this day, for childhood traumas. (Photo by Alec Soth for the New Yorker) As you would expect, the article includes a number of outrageous and offensive remarks and claims made by Fischer, both to Mayer and previously (many of which were first reported on this blog). Here are some notable examples from the profile:- “Fischer declared that ‘homosexuality gave us Adolf Hitler, and homosexuals in the military gave us the Brown Shirts, the Nazi war machine, and six million dead Jews.’

- “Like the saying goes, ‘I’ve never met an ex- black, but I’ve met a lot of ex-gays.’ If one person can do it, two people can do it.”

- “He then denied, as he does routinely, that H.I.V. causes AIDS, calling it a ‘harmless passenger virus.’”

- “Fischer thinks that Islam is a violent religion, and argues that Muslims should be stopped from immigrating and barred from serving in the U.S. military. He believes that the country was a Christian nation when the Bill of Rights was written, and therefore non-Christians ‘have no First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion.’ He has said that Native Americans are ‘morally disqualified’ from ruling America, and that African-American welfare recipients ‘rut like rabbits.’”

- “Obama, he has said, ‘despises the Constitution” and “nurtures a hatred for the white man.’”

- “Fischer advised a caller that, in some instances, a child as young as six months could be spanked.”

Fischer’s political activism, however, began years before the advent of same-sex-marriage laws. In fact, his preoccupation with family dysfunction seems to have started with his own. Though Fischer loves to talk, he does not like to talk about his childhood, and spoke about it only grudgingly. He was born in Oklahoma City, in 1951, and his father, John, a descendant of German Mennonites, was a Conservative Baptist minister whose pacifism was so strict that he became a conscientious objector during the Second World War—a choice that makes Fischer uncomfortable. […] Fischer didn’t volunteer anything about his mother, but, when pressed, said, “My parents divorced when I was about twenty. It just rocked my world.” His mother, who worked as an interior decorator at a furniture store, was “chronically late,” and the bus driver on her route to work would always hold the bus for her. Eventually, he said, “my mom fell for the bus driver,” deserting him, his father, and his younger sister. “I don’t want to go into it,” Fischer said. “But I saw the devastating impact it had on other people in my immediate family.” Asked how his father fared, Fischer turned away, then said, “He looked like an Auschwitz survivor. It was akin to that ordeal.” Dennis Mansfield, a Christian conservative who was friends with Fischer for twenty years, said that Fischer also “had a deep-rooted disappointment in his father, for not being strong enough.”Later, as a student at Stanford, Fischer gravitated to David Roper, a chaplain at the school, and began attending his evangelical church in Palo Alto. Fischer told Mayer that he was attracted by the “manliness” of the church: “It was the first time I’d been around a real muscular Christianity,” he told me. “It had a kind of strength and virility to it that would appeal to men.” Roper told Mayer he found this characterization “odd” and is no longer close to Fischer. Manliness and strength continued to be major forces – and sources of strife – in Fischer’s life. Roper left Palo Alto in 1978 and recruited Fischer and Terry Papé, a fellow student, to join him in Boise after they graduated. In 1993, Roper retired and chose Papé to lead the congregation, passing over Fischer, who was crushed. Manliness was to blame:

“Bryan was very popular when he came to Cole,” Papé recalled. “But, over time, those relationships were strained, because of his very strong personality. When it comes to his perspective, it’s very difficult to get him to budge. He loves a good argument, but he doesn’t like being persuaded he might be wrong.” In 1993, Fischer was crushed when Roper retired and endorsed a different successor. […] But friction had grown between the two men—and between Fischer and the congregation— over various doctrinal issues. “The central issue was gender,” Fischer told me. The church, he said, had “adopted policies that would have allowed women to exercise authority over men.” He opposed this, citing the Apostle Paul.Fischer then started his own church in Boise, the Community Church of the Valley, and pursued a hard line on gender and family issues:

In church, Fischer preached that it might be preferable if Americans married upon becoming sexually mature. “I’m not saying go out and get your fifteen-year-old engaged,” he said. But he argued that “we have artificially delayed the age at which people are expected to marry,” and observed, “Mary, the mother of Christ, was probably a teen-ager when she was betrothed to Joseph.” In another sermon, he preached that women were equal to men in worth but “not equal in authority.” “Somebody’s got to have the tie-breaking vote,” he explained to me. “According to God, that’s the husband and father.”Fischer was appointed in 2001 as the chaplain of the Idaho Senate and began developing a statewide reputation for hard-right political activism. He also alienated many people, including Dennis Mansfield, an elder at his church and a longtime friend, who told Mayer about a pattern he noticed over the years: Fischer would “develop a closeness to a friend and then, as soon as they had a disagreement, they’d be cut adrift.” Four years later, Fischer was kicked out on the street by his own congregation – again manliness was to blame:

“It was the gender issue again,” Fischer told me. “Because of my Scriptural convictions, I wasn’t able to budge. A female friend of the wife of an elder wanted a leadership role. I felt those roles should be reserved for men… . When I objected, they said, ‘You’re fired.’ It was very abrupt. I didn’t know what I was going to do next. It was very painful.”Fischer then fell into full-time political activism, founding the Idaho Values Alliance, which in 2007 became the state chapter of the American Family Association. Two years later he moved to Tupelo, MS to take on his current roles at AFA’s headquarters, which features a “statue of a fetus enshrined in a heart and a shoulder-high stone tablet inscribed with the Ten Commandments” out front. Mayer’s profile provides an interesting look inside AFA, the tax-exempt and supposedly nonpartisan organization behind American Family Radio, which “comprises two hundred stations in thirty-five states.” At one point, Fischer’s producer began laughing after saying that “we have to be careful, because we’re not allowed to endorse.” Mayer also relays a story about how AFA president Tim Wildmon texted Fischer during an on-air tirade about Newt Gingrich’s infidelities to warn him that “he might be alienating listeners.” This anecdote caught my attention because we’ve noted instances in the past where AFA has censored and edited Fischer’s articles on their website. Could it be that Fischer is on course to alienate yet another friend and benefactor? Only time will tell.