Far Right extremists are counting on President Trump’s Supreme Court nominee to eventually cast the fifth vote to overrule Roe v. Wade, Obergefell v. Hodges, and other foundational decisions protecting our basic rights and liberties. Others on the right have their eyes on precedents recognizing Americans’ ability to act through our government to impose reasonable limits on powerful corporations, including through federal administrative agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Labor Relations Board, and the Food and Drug Administration. Our rights have been recognized and protected in Supreme Court precedents established before many voters were even alive.

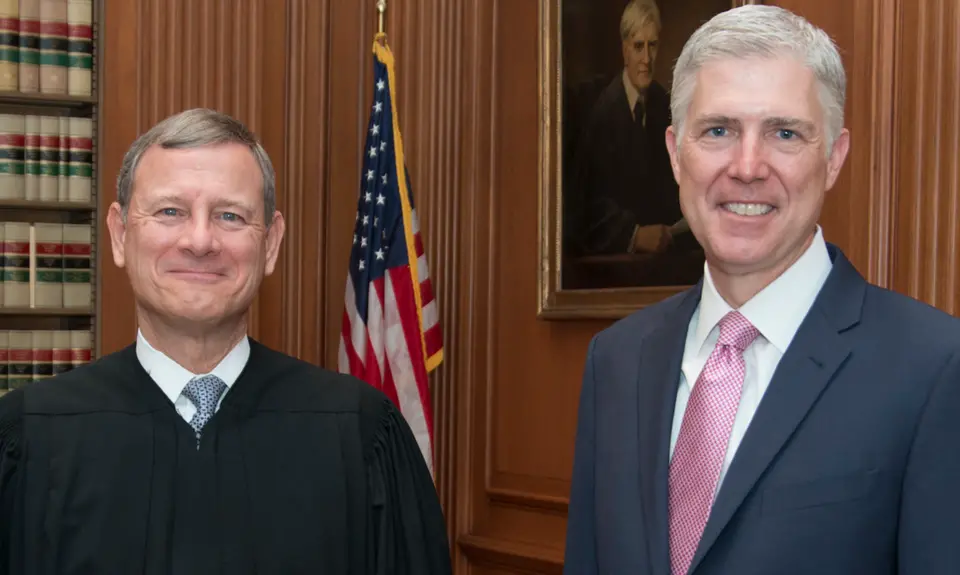

No doubt the nominee will be coached in how to persuasively say they will respect precedent, just as other members of the Court did at their own confirmation hearings. In the case of Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch (as with Justices Scalia and Kennedy), their records, once confirmed to their lifetime positions, speak louder than their assurances beforehand. They have not shied away from overruling precedent they disapprove when they can get a majority, and urging for such action when they don’t yet have that majority.

As the examples below show, they have overruled no fewer than eight precedents across numerous issue areas since 2007.1 2 They have also frequently overruled cases without acknowledging that that’s what they are doing. In still other instances, the conservative justices have signaled their desire to overrule precedent but lack the votes to do so.

Overruling Done Openly

Money in Politics: Citizens United, 2010

One of the most infamous and debilitating examples is Citizens United v. FEC. In an aggressively political act, the majority chose not to decide the case before them, but instead to have the parties argue a new issue not raised in their pleadings. This positioned them to be able to overrule two important precedents limiting the influence of corporate money on our elections. In a 5-4 ruling, the conservatives overruled Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, 494 U.S. 652 (1990), which had upheld a state ban on corporate independent expenditures, and the part of McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93 (2003), that had upheld restrictions on corporate independent expenditures. Corporations can now spend unlimited amounts to affect elections.

Writing about the concept of precedent in a concurring opinion, the Chief Justice wrote that its “greatest purpose is to serve a constitutional ideal—the rule of law. It follows that in the unusual circumstance when fidelity to any particular precedent does more to damage this constitutional ideal than to advance it, we must be more willing to depart from that precedent.” Of course, such a general statement does nothing to signal when that point is reached, to say nothing about whether a precedent was wrongly decided in the first place.

Corporate Power and the Rights of Working People: Janus v. AFSCME, 2018

In a 5-4 ruling by Justice Alito, the conservatives overruled a seminal 1977 case on the rights of working people (Abood v. Detroit Board of Education). The Court struck down requirements that public sector employees who are not members of the unions that are required by law to represent them pay “fair share” fees to cover the costs of that representation. According to the majority, those requirements force non-members to pay for speech on public matters (government spending) that they disagree with, an assertion rejected by conservative legal writers such as Eugene Volokh and William Baude. Other conservatives outside the Court were much more frank in stating that their goal was to destroy public sector unions in order to eliminate their impact on elections.

Justice Kagan’s dissent (joined by the other three moderates) called Alito and his fellow conservatives out for weaponizing the First Amendment to impose their own policy choices on the nation, with Janus just being the latest example.

Speech is everywhere—a part of every human activity (employment, health care, securities trading, you name it). For that reason, almost all economic and regulatory policy affects or touches speech. So the majority’s road runs long. And at every stop are black-robed rulers overriding citizens’ choices. The First Amendment was meant for better things. It was meant not to undermine but to protect democratic governance—including over the role of public-sector unions.

Antitrust: Leegin Creative Leather Products v. PSKS, 2007

In a 5-4 antitrust ruling on resale price maintenance, the five right-wing justices overruled a century-old case called Dr. Miles Medical Co. v. John D. Park & Sons Co. (1911). Dr. Miles established a bright-line rule that agreements fixing minimum resale prices are per se illegal under the Sherman Act. In 2007, the conservatives, citing “respected economic analysts,” concluded that vertical price restraints can have pro-competitive effects. (Interestingly, in the Kimble patent law case discussed below, Roberts, Thomas, and Alito sharply criticized a precedent they wanted to overrule for relying on an economic theory rather than a statutory interpretation.)

Writing for the moderates, Justice Breyer criticized the majority for relying on a set of economic theories that have been well known for nearly 50 years, and which Congress had repeatedly found insufficient grounds for amending the Sherman Act to override Dr. Miles.

Right to Counsel: Montejo v. Louisiana, 2009

In this 5-4 ruling, the ultra-conservatives overruled an important criminal justice precedent from 1986. In Michigan v. Jackson, the Court had held that once an accused person has claimed their right to counsel at a court proceeding, any waiver of that right during subsequent police questioning is invalid unless the accused person initiates the conversation with police. This helped protect people from surrendering a constitutional right under nonstop pressure from law enforcement. But the five conservatives stripped Americans of this protection in 2009 in Montejo v. Louisiana, calling the precedent “unworkable.”

Justice Stevens wrote in the main dissent:

Today the Court properly concludes that the Louisiana Supreme Court’s parsimonious reading of our decision in Michigan v. Jackson is indefensible. Yet the Court does not reverse. Rather, on its own initiative and without any evidence that the longstanding Sixth Amendment protections established in Jackson have caused any harm to the workings of the criminal justice system, the Court rejects Jackson outright on the ground that it is “untenable as a theoretical and doctrinal matter.” That conclusion rests on a misinterpretation of Jackson’s rationale and a gross undervaluation of the rule of stare decisis. The police interrogation in this case clearly violated petitioner’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel. [internal citations removed]

Closing the Courthouse Door by Overruling Equitable Exceptions for Unique Circumstances: Bowles v. Russell, 127 S.Ct. 2360, 2007

Justice Thomas wrote a 5-4 ruling holding that a litigant who had filed an appeal within the time given to him by a federal district court judge nonetheless could not pursue that appeal when it turned out that the judge’s order had given the litigant three days longer to appeal than the applicable statute allowed. The conservative majority held that Bowles’s “untimely filing” could not be excused under the doctrine of “unique circumstances,” which dated back to Harris Truck Lines, Inc. v. Cherry Meat Packers (1962) and Thompson v. INS (1964), both decided per curiam. They considered this a jurisdictional issue (unlike the dissenters), wrote that the Court cannot make an exception to a jurisdictional bar, and overruled both cases as “illegitimate.”

Souter dissented, joined by the other moderates: “It is intolerable for the judicial system to treat people this way, and there is not even a technical justification for condoning this bait and switch.” The dissent noted that just one year earlier, in a case called Arbaugh v. Y & H Corporation that was decided unanimously with Alito not participating, the Court had made clear that a time limit like this is not jurisdictional:

“Jurisdiction,” this Court has observed, “is a word of many, too many, meanings.” Steel Co. v. Citizens for Better Environment, 523 U. S. 83, 90 (1998) (internal quotation marks omitted). This Court, no less than other courts, has sometimes been profligate in its use of the term. For example, this Court and others have occasionally described a nonextendable time limit as “mandatory and jurisdictional.” See, e. g., United States v. Robinson, 361 U. S. 220, 229 (1960). But in recent decisions, we have clarified that time prescriptions, however emphatic, “are not properly typed ‘jurisdictional.’” Scarborough v. Principi, 541 U. S. 401, 414 (2004); accord Eberhart v. United States, ante, at 16–19 (per curiam); Kontrick, 540 U. S., at 454–455. See also Carlisle v. United States, 517 U. S. 416, 434–435 (1996) (Ginsburg, J., concurring). [emphasis added]

As the New York Times editorialized:

“If the Supreme Court, with its new conservative majority, wanted to announce that it was getting out of the fairness business, it could hardly have done better than its decision last week in the case of Keith Bowles.”

Overruling or Hollowing Out Precedent Without Admitting It

Money in Politics: McCutcheon v. FEC, 2014

In a 5-4 ruling, the conservative majority struck down federal limits that capped aggregate campaign contributions during a single election cycle — limits that the Court had upheld in 1976 in Buckley v. Valeo. But rather than acknowledge that the Court was overruling precedent, Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the four-Justice plurality that Buckley was not controlling because that section of the decades-old opinion was not long enough and the parties at the time had not devoted enough time separately addressing that specific issue among all the many complex issues involved in that seminal campaign finance case. (It was a plurality because Justice Thomas concurred only in the judgment, writing that Buckley should be overruled.) Writing in dissent, Justice Breyer criticized the conservatives for overruling the aggregate contributions holding of Buckley based not on a factual record, but on its own view of the facts instead.

Right to Vote: Shelby County v. Holder, 2013

In an extremely destructive 5-4 ruling, the conservatives struck down the Voting Rights Act’s formula for determining which states were subject to the preclearance requirement of Section 5. The majority concluded that the formula was outdated and therefore violated the equal sovereignty of the states. The majority did not frame its decision as overruling precedent, but that is exactly what it did. In South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966), the Supreme Court upheld the preclearance requirement. Katzenbach held that the concept of equal sovereignty “applies only to the terms upon which States are admitted to the Union, and not to the remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared.” Katzenbach further held that—regardless of the powers ordinarily reserved to the states—Congress could use “any rational means to effectuate the constitutional prohibition of racial discrimination in voting. Dissenting in the Shelby County case, Justice Ginsburg observed that the conservative majority did not follow the “rational means” test, yet did not purport to alter the precedent mandating that deference to Congress in this area.

Corporate Power and the Rights of Working People: Knox v. SEIU, 2012

The conservatives used Knox as a prelude to the Janus decision discussed above. The case was decided 7-2, but the five ultra-conservatives (without the support of any other justices) chose to address an additional issue, not raised in the petitioners’ briefing and unnecessary to deciding the case. By a 5-4 vote, they imposed a requirement that special assessments or increases in fair-share fees for public sector unions be administered on an opt-in basis, that is workers were required to affirmatively agree to the special assessments or increases. As justification, the majority wrote that fair-share fees represent such a violation of non-members’ First Amendment rights that an opt-out process for special assessments would not be acceptable. Of course, that conclusion was exactly the opposite of that established in Abood, the precedent the majority made clear they wanted to overrule, as they ultimately did on a formal basis in Janus.

Justice Sotomayor noted in her dissent that the conservatives reached out to decide an issue not raised by the parties and overrule precedents that consistently recognized the constitutionality of opt-out procedures. She pointed out the illegitimacy of the decision:

Petitioners did not question the validity of our precedents, which consistently have recognized that an opt-out system of fee collection comports with the Constitution. See Davenport v. Washington Ed. Assn., 551 U. S. 177, 181, 185 (2007); Hudson, 475 U. S., at 306, n. 16; Abood v. Detroit Bd. of Ed., 431 U. S. 209, 238 (1977); see also ante, at 12–13. They did not argue that the Constitution requires an opt-in system of fee collection in the context of special assessments or dues increases or, indeed, in any context. Not surprisingly, respondents [SEIU] did not address such a prospect.

Under this Court’s Rule 14.1(a), “[o]nly the questions set out in the petition, or fairly included therein, will be considered by the Court.” …

The majority’s refusal to abide by standard rules of appellate practice is unfair to the Circuit, which did not pass on this question, and especially to the respondent here, who suffers a loss in this Court without ever having an opportunity to address the merits of the question the Court decides.

Labor Law and Overtime: Encino Motorcars v. Navarro, 2018

Justice Thomas wrote the opinion in this 5-4 ruling that some 100,000 service advisors who work for auto dealerships are not entitled to overtime pay under federal law. He was joined by his fellow ultra-conservatives. As Justice Ginsburg wrote in dissent, this undermined more than 50 years of Supreme Court precedent that had narrowly interpreted exemptions to overtime pay requirements and thus provided important protection to vulnerable workers.

Freedom of Speech: Morse v. Frederick, 2007

The Court ruled 5-4 against a high school student who was suspended for holding up a sign saying “bong hits for Jesus” as the Olympic Torch was carried past his school. The conservative majority claimed this was not inconsistent with Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, which had famously held that students don’t “shed their constitutional rights . . . at the schoolhouse gate.” The conservative majority claimed this was different from Tinker, which was about core political speech (students’ right to wear black armbands opposing the Vietnam War).

Thomas wrote a concurrence saying he would overrule Tinker altogether rather than make an exception to it, based in large part on his analysis of education in colonial America.

Women’s Health and Reproductive Freedom: Gonzales v. Carhart, 2007

Soon after Justice O’Connor was replaced by Justice Alito, the conservatives prevailed in a 5-4 ruling upholding the federal ban on certain types of abortions, even though it lacked an exception to protect women’s health. This contrasted with a 5-4 ruling in 2000’s Stenberg v. Carhart striking down a similar state ban, where Justice O’Connor had been with the majority.

Although the five conservatives did not characterize themselves as overruling the 2000 precedent, the stark discrepancy between the two rulings prompted Justice Ginsburg to note in dissent that the result was due solely to the change in justices: “the Court, differently composed than it was when we last considered a restrictive abortion regulation, is hardly faithful to our earlier invocations of ‘the rule of law’ and the ‘principles of stare decisis.’”

The conservatives’ disregard for abortion rights precedent went even further. They wrote that they would “assume [the holdings of Roe, Casey, and related cases] for the purposes of this opinion,” which is at best an unusual way to frame precedent. Since Justice Kennedy later recognized them as precedent in the Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt case striking down TRAP laws in Texas, it seems likely that one or more of the other four conservatives would not sign on to an opinion acknowledging Roe.

Gun Violence: District of Columbia v. Heller, 2008

Without acknowledging it, the conservative 5-4 majority overruled United States v. Miller (1939), which had held that the Second Amendment guarantees no right to keep and bear a firearm that does not have “some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia.” They ruled that the Second Amendment grants a personal right to firearms unrelated to military service.

Efforts to Overrule Precedents That Have Not Yet Gotten a Majority

Money in Politics: Randall v. Sorrell, 2006

In a 6-3 decision, the Court struck down Vermont’s campaign contribution and expenditure limits as violating the First Amendment. There was no majority opinion, but the plurality relied on Buckley v. Valeo. Justice Thomas concurred only in the judgment. He wrote that Buckley was wrongly decided and that contribution limits should have been subject to the same strict scrutiny as spending limits. He also would have overruled Buckley rather than follow stare decisis.

Justice in the Criminal Justice System: Erickson v. Pardus, 2007

This Eighth Amendment case involved a prisoner who was denied medical treatment for Hepatitis C. The Court issued a per curiam ruling in the prisoner’s favor. In dissent, Justice Thomas called for overruling “the Court’s flawed Eighth Amendment jurisprudence.” According to Thomas, the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment should only protect individuals from serious injuries, not exposures to risks of injury.

Patent Law: Kimble v. Marvel Enterprises, 2015

Justice Kagan authored a 6-3 opinion (joined by the moderates plus Kennedy and Scalia) choosing not to overrule a wrongly-decided precedent called Brulotte v. Thys Co., 379 U.S. 29 (1964). Brulotte interpreted the Patent Act to prohibit parties from entering into a patent licensing agreement that provides for royalty payments to continue after the term of the patent expires. Kagan (joined by the moderates plus Kennedy and Scalia) described why stare decisis should be upheld and the precedent not overruled.

All three of the arch-conservatives still on the Court would have overruled this statutory precedent. Justice Alito wrote the dissent, joined by Roberts and Thomas. Although the Court has long had a practice of adhering to statutory precedent much more than to constitutional precedent (because Congress can fix it if the Court gets it wrong), the conservatives were nonetheless eager to overrule Brulotte. The dissenters argued that the majority placed too much weight on the fact that Congress hadn’t passed legislation overturning the result in Brulotte, since it is was hard to pass legislation at all. The conservatives also condemned Brulotte as not having been based on the Patent Act but instead being based on an economic theory that they disagreed with.

Suing a State in Another State’s Court: Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, 2016

In 2016, the Court split 4-4 on whether to overrule Nevada v. Hall (1979), in which the Court allowed people to sue a state in another state’s court without the defendant state’s consent. (In that case, a Nevada vehicle on official state business in California collided with another car; the California passengers were allowed to go to the California courts and sue the state of Nevada.)

Oral arguments suggested the moderate justices wanted to retain the precedent, per SCOTUSBlog. The Court has taken the case again for the next term. It seems that the conservatives very much want to issue a ruling overruling Hall.

Conclusion

Just as the Court took a dramatic rightward turn when Alito replaced O’Connor, it is poised to lurch even farther rightward if the Senate allows Trump to replace Kennedy with anyone from his list of potential justices. Even more precedent would be likely to fall.

- The majority and the dissent in the 5-4 case of Trump v. Hawaii (2018) upholding President Trump’s Muslim ban all agreed that the Korematsu case (1944) (which upheld the internment of Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants) should be overruled. The conservative majority brought it up because the dissenters raised “the stark parallels between the reasoning of this case” and Korematsu. The majority denied the charge. Justice Sotomayor, joined by the other moderates, wrote:

This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue. But it does not make the majority’s decision here acceptable or right. By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying Korematsu and merely replaces one gravely wrong decision with another. [internal quotation marks and citation removed]

- Precedents were also overruled in cases with an atypical alignment of justices. Alleyne v. U.S. (2013) was a 5-4 ruling with an opinion authored by Justice Thomas and joined by the four moderates. Overruling Harris v. U.S. (2002), the Court held that because mandatory minimum sentences increase the penalty for a crime, any fact that increases the mandatory minimum is an “element” that must be submitted to the jury. South Dakota v. Wayfair (2018) overruled two “dormant commerce” cases in a 5-4 opinion by Justice Kennedy, joined by Justices Thomas, Ginsburg, Alito, and Gorsuch. The case allows states to tax online sales by companies not physically present in the state. The four dissenters agreed the original decisions prohibiting such a sales tax were wrongly decided, but that stare decisis should be followed. ↩