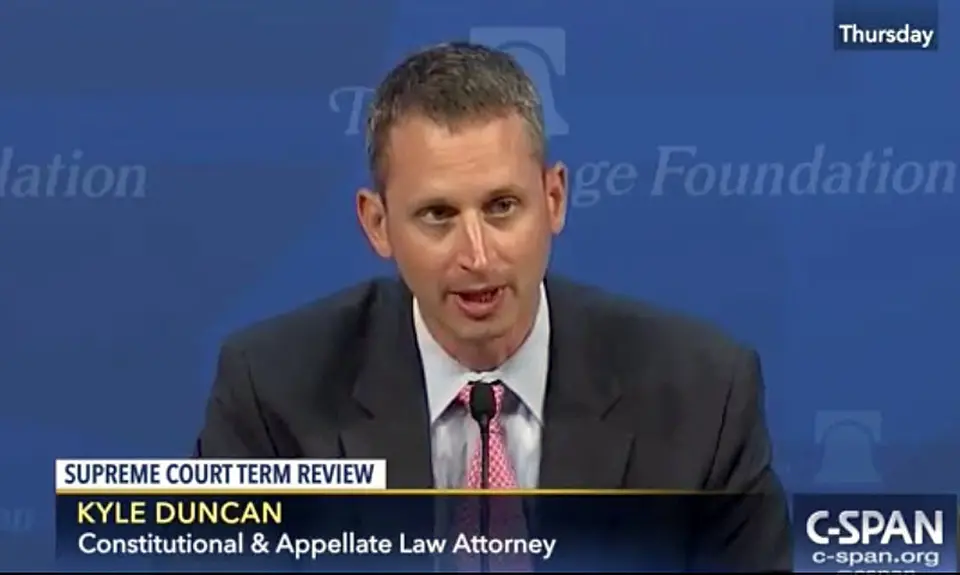

At the November 29 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing for judicial nominees David Stras (Eighth Circuit) and Kyle Duncan (Fifth Circuit), Louisiana Sen. John Kennedy ended his questioning by posing a hypothetical to both nominees about what they would do if Supreme Court precedent came into conflict with their own beliefs. Rather than answer directly, Duncan gave a response that increases concerns that he intends to use the bench as a platform to impose his own political ideology.

Kennedy wanted some reassurance that the nominees would put their own beliefs aside and adhere to precedent even if they disagreed strongly with it. Indeed, it is likely very difficult emotionally to issue a ruling based on a precedent that you believe to your core was wrongly decided and harmful to the nation. But that is what judges have to do in a nation governed by the rule of law.

Acknowledging the unlikelihood of this ever happening, Kennedy posed a simple hypothetical: Say the Supreme Court overrules Brown v. Board of Education and reinstates the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 decision that upheld Jim Crow laws for half a century. As a judge on the circuit court, which is required to follow Supreme Court precedent, what do you do?

It is one thing to say you’ll follow precedent in general, but Kennedy made giving a glib response more difficult by naming a specific precedent that he assumed the nominees would find repellant.

Stras went first: “I would not like it, but it’s our duty to follow United States Supreme Court precedent. … I’m going to do it, because that’s part of what I took an oath to do.” His answer was clear and unequivocal.

Duncan could have given the same response. He should have given the same response. But he didn’t.

Clearly uncomfortable with the idea of adhering to a precedent he finds personally noxious, he initially dissembled. He expressed regret that Plessy arose from a Jim Crow law in Louisiana, the state where he used to live. Then he said that he’d pray that states would not choose to exercise their option to re-impose a regime of enforced segregation.

But if he had such a case before him as a circuit judge, he told Kennedy that “I’d apply the Fourteenth Amendment. And I’d go and read scholars like Michael McConnell and others about the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.” After a brief pause, he continued: “And I’d hope we’d get Brown back really quick.”

Duncan’s response is telling. He did not say that he would follow the clear precedent of the United States Supreme Court. Instead, he would do his own personal research in order to find an excuse not to adhere to unambiguously applicable precedent that he presumably believes to be morally wrong and legally unsound.

As Sen. Kennedy noted, the hypothetical is unlikely to actually occur. But the thought exercise he gave the two nominees served its purpose, ferreting out Duncan’s willingness to do whatever possible to impose his own views in certain areas regardless of precedent.

I doubt that is what Kennedy was hoping to hear. He did not get the assurance he was likely looking for, and neither did the American people.