“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

Trump DC Circuit judge Neomi Rao argued in dissent that it was improper to even challenge in court a decision by the Trump Administration to subject many more immigrants to expedited removal without a hearing and other protections. Although the majority upheld the policy from a challenge under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), it rejected Rao’s claim that it had no jurisdiction to hear the dispute and that other challenges to the rule cannot be adjudicated. The June 2020 ruling on was Make the Road New York v. Wolf.

Under federal immigration law, before most immigrants can be deported, they must receive a hearing before an immigration judge where they can present evidence and cross-examine witnesses, and a deportation order can be appealed administratively and in court. In the late 1990s, Congress passed a law that allows expedited removal of those who are just entering the US or have been here for a short period. Under expedited removal, an agency official can determine that a person does not have valid entry documents or visa and order them immediately deported, without a hearing or other review other than “a paper review” by the official’s supervisor. Even if the person wants to seek asylum, the law provides for a “highly expedited” determination by an immigration judge, with no administrative or judicial appeal.

Until the Trump Administration, expedited removal had been used only with respect to a limited category of immigrants, including only those who had been taken into custody within 100 miles of the Mexican border and when they have been in the US for less than two weeks. In January 2017, however, President Trump ordered the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to expand expedited removal to its “full statutory limits,” which could include anyone picked up anywhere in the country who has been here for less than two continuous years. Advocates estimate that this could subject “hundreds of thousands” of additional people to expedited removal.

When DHS issued regulations doing just that in 2019, they were challenged in court by several organizations representing immigrants. The lawsuit contended that the regulations were issued in violation of the APA, and that they also violated federal immigration law and the constitution. A federal judge in DC found that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed on their APA claims, and issued a preliminary injunction against the rules on that ground. The government appealed to the DC Circuit.

In an opinion by Judge Patricia Millett, which was joined by Judge Harry Edwards, the DC Circuit reversed. Although the majority agreed that the lower court properly had jurisdiction to hear the challenge, they found that the injunction had to be reversed because Congress had committed the decision whether to expand expedited removal to the “sole and unreviewable” discretion of the Secretary of DHS, and the decision was thus not subject to substantive review under the APA. The court then sent the case back for further proceedings, which could well include adjudication of the statutory and constitutional claims.

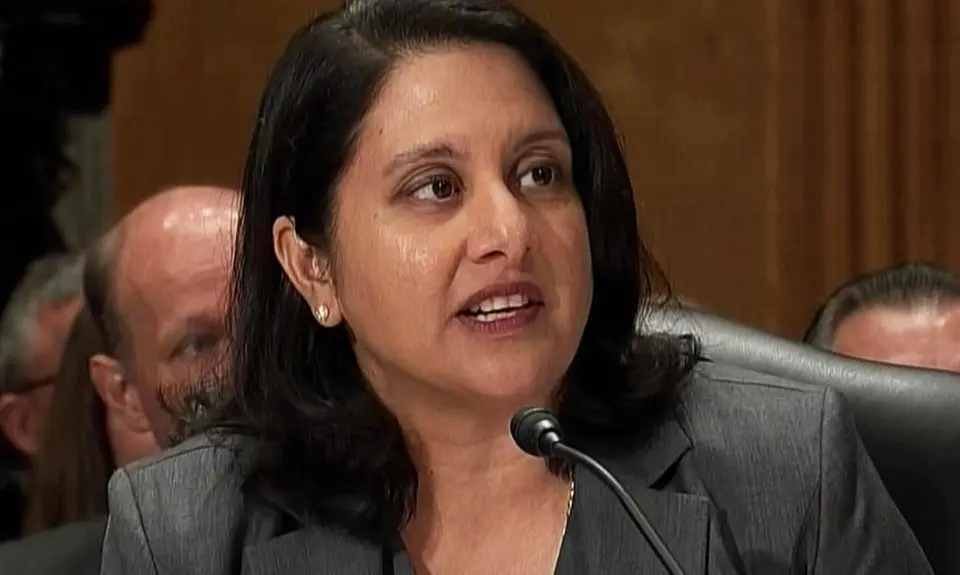

Judge Neomi Rao dissented—not because she thought the injunction should be upheld, but because she thought that the court should have ruled that no court has jurisdiction to hear any challenge to the regulations on any grounds. Rao claimed that in addition to committing the expansion decision to the DHS’ Secretary’s discretion, the immigration law “expressly bars the courts” from any review, and Congress had deprived the courts of any jurisdiction over the issue. In short, she maintained, the law passed by Congress “strips jurisdiction” over the issue from the courts.

The majority strongly disagreed with Rao. Based on a careful analysis of Supreme Court and other precedent on “strong presumptions” in favor of judicial review, as well as the text and statutory structure of the law, the majority ruled that the statute “expressly preserves jurisdiction over challenges” to rules like the one promulgated by DHS. Although the law limited the ability of anyone subject to expedited removal to challenge individual deportation in court, the majority went on, the “statutory text” makes clear that regulations can be challenged on constitutional and statutory grounds. Rao’s argument to the contrary, the majority concluded, “forsakes the text of the statute.”

After the court’s ruling, lawyers for the plaintiffs made clear that they will “now pursue our statutory and constitutional claims in order to once again block this cruel policy.” If it had been up to Rao, however, no such challenges could be brought, even if the new rules are blatantly unconstitutional.