“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties.

Trump 4th Circuit Judges Marvin Quattlebaum and Julius Richardson joined a harsh July dissent in Manning v. Caldwell where the full court majority decided 8-7 that a challenge can proceed to a Virginia law that targets people who are homeless and struggle with alcoholism for arrest and imprisonment. If Trump’s most recent 4th Circuit nominee Allison Rushing had been confirmed in time to participate in the case, the court could well have voted to prevent any challenge to the law.

Under Virginia statutes, a person can be declared a “habitual drunkard” by a state civil court in what is called an interdiction proceeding, a hearing that usually involves the local district attorney but occurs when the person targeted has no right to be (and often is not) present. Once interdicted, a person is subject to arrest and imprisonment for up to one year for conduct that is legal for anyone else—“consuming, purchasing, or possessing” any alcoholic beverage, or attempting to do so.

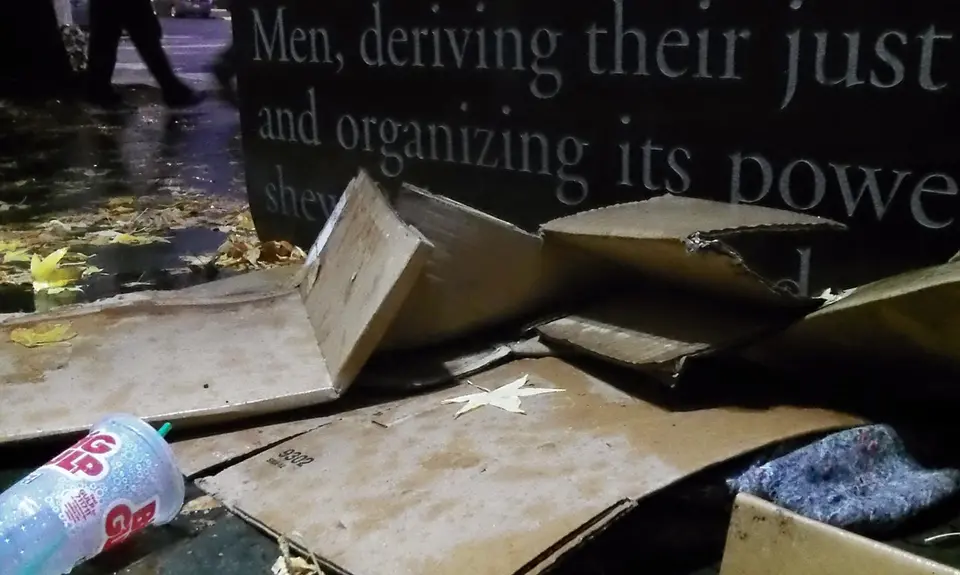

A group of men who are both experiencing homelessness and suffering from alcoholism challenged the “statutory scheme” as unconstitutionally vague (because it offers no guidance on what makes someone a “habitual drunkard”) and as violating the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment (because it effectively criminalizes the disease of alcoholism as applied to them). The plaintiffs’ complaint alleged that “in practice,” the scheme “functions as a tool to rid the streets of particularly vulnerable, unwanted alcoholics” who are homeless. Some contended they had been “prosecuted as many as 25 to 30 times” and faced prison for up to one year for “conduct permitted for all others of legal drinking age.” The men also maintained that the “habitual drunkard” label has harmed their ability to secure employment and housing.

Both the district court and a panel of the court of appeals rejected the claim as a matter of law, based largely on a 1979 district court ruling upholding the scheme that was summarily affirmed by the court of appeals without any opinion. The full 4 th Circuit decided to rehear the case and ruled 8-7 that the plaintiffs should be able to go forward with their claim and that the prior decision was incorrect

The majority explained that the term “habitual drunkard” subjected people to criminal prosecution and imprisonment, but did not “provide any meaningful guidance regarding proscribed conduct.” This was in marked contrast to the Virginia statutory term “intoxicated,” the majority pointed out, which is “expressly defined” as a condition in which a person has “drunk enough alcoholic beverages to observably affect his manner, disposition, speech, muscular movement, general appearance, or behavior.” Thus, there is clear notification in the law of the conditions under which a person “may be charged with public intoxication,” the majority went on, but no “substantive guidance” on what makes a person a “habitual drunkard.” In light of the criminal consequences to people assigned that label, without even an opportunity to present countervailing evidence, the majority concluded that under Supreme Court and other precedent, the statute was “unconstitutionally vague” because it “invites the very type of arbitrary enforcement that the Constitution’s prohibition against vague statutes is designed to prevent.”

In addition, the majority explained that the plaintiffs should be allowed to go forward to try to prove that the law violated the 8th Amendment, pointing out that the Supreme Court ruled more than 50 years ago that it is cruel and unusual punishment to criminalize addiction “to the use of narcotics” because a state cannot constitutionally “punish a person for an illness.” But the three-judge panel decision, as well as the dissent in the en banc court ruling, relied on a later decision where the Court upheld a conviction for “public intoxication” in which the plurality had relied on the difference between the “status” of being addicted to alcohol and the “act” of public intoxication, claiming that this “act-status” distinction applied here. As the full court majority explained, however, this analysis ignored the fact that the fifth Supreme Court vote that upheld the public intoxication conviction “expressly rejected the act-status rationale” and specifically noted that a “chronic alcoholic” should “not be punishable for drinking or for being drunk.” In this case, the majority went on, the plaintiffs were contending that they were being targeted for special punishment for “conduct that is both compelled by their illness” of alcoholism and is “otherwise lawful for all those of legal drinking age.” If these allegations are proven true, the majority concluded, the challenged scheme violates the 8th Amendment.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson wrote a harsh dissent, which was joined by Quattlebaum, Richardson, and several others, accusing the majority of attempting to “usurp the American Constitution.” In addition to the “act-status” claim discussed above concerning the 8th Amendment, the dissent argued against the majority’s vagueness holding, noting that there are accepted dictionary definitions of “drunkard” as someone who “habitually consumes alcoholic beverages excessively” and that such definitions are sufficient. But as the majority pointed out in response, such general definitions “entirely” fail to answer such questions as how much consumption is excessive and how frequent the consumption must be, and thus fail to provide any “meaningful guidance” as required by the Constitution. The dissent further argued that the “sole purpose” of interdiction is to “provide notice” about the type of conduct Virginia prohibits, but the majority pointed out that the scheme nevertheless fails to provide any notice to those labelled as “habitual drunkards” about “what conduct led” to that label "in the first place."

At the time the full court considered this case, Trump’s third Fourth Circuit nominee Allison Rushing was not yet on the bench . Had she been confirmed earlier and voted with her colleagues, the result would have been an 8-8 tie and the law would have been upheld with no opportunity to challenge it. Fortunately, as the majority opinion concluded, as a result of its ruling, “the many homeless citizens of Virginia who struggle with the effects of alcohol on their mental and physical health” will find “at least the government will not be compounding their problems by subjecting them to incarceration” based on the “arbitrary enforcement of ambiguous laws” or the “targeted criminalization of their illness.”

Today, we know that addiction is a treatable disease; a wealth of medical and psychiatric data support that fact. Yet Quattlebaum’s and Richardson’s dissent stereotyped these men as irresponsible criminals. These dangerous views only serve to perpetuate the criminalization of addiction and the cycle of poverty and homelessness that often accompany the disease.