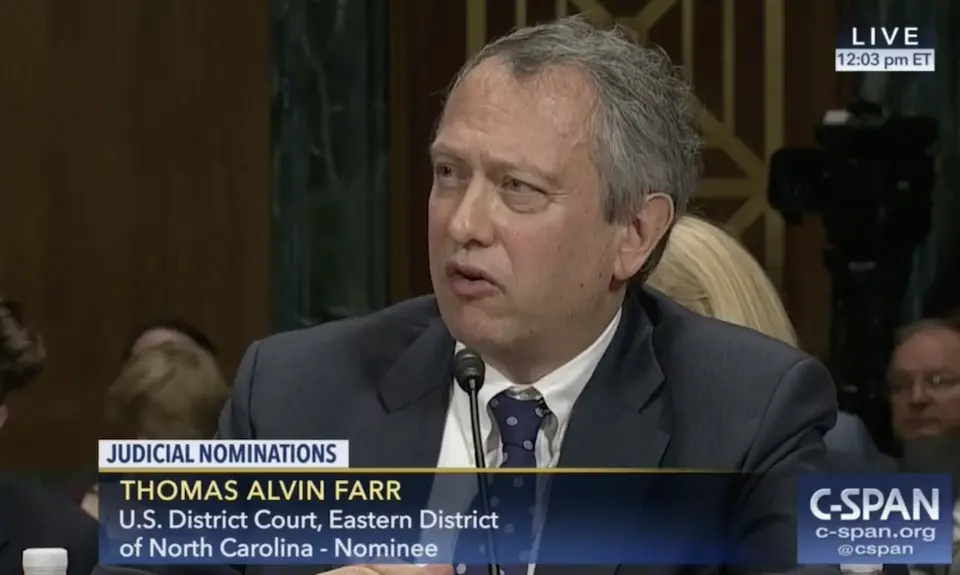

In announcing his opposition to confirming Thomas Farr to be a federal judge, Sen. Tim Scott cited newly disclosed Justice Department records from the 1990s demonstrating just how bad Farr’s actions to suppress the vote have been. On November 29, Sen. Scott explained his opposition:

This week, a Department of Justice memo written under President George H.W. Bush was released that shed new light on Mr. Farr’s activities. This, in turn, created more concerns. Weighing these important factors, this afternoon I concluded that I could not support Mr. Farr’s nomination.

Scott’s statement highlights one lesson to be drawn from Farr’s nomination: Farr, like many of President Trump’s nominees, had a record that the Judiciary Committee under Chuck Grassley failed to adequately examine. The next chairman must take his responsibilities to the nation more seriously.

The 1991 DOJ memo detailed Farr’s deep involvement in projects designed to prevent African Americans from voting in Jesse Helms’ 1984 and 1990 reelection campaigns. This “smoking-gun” document contradicted Farr’s claims of ignorance that he had made to the Judiciary Committee under oath under penalty of perjury in 2017, when he was asked about the 1990 campaign.

But this is not the first such evidence to have surfaced after Farr’s confirmation hearing and party-line committee vote. In November 2017, evidence surfaced that he had been at a “ballot security” planning meeting in 1990 where that year’s scheme was discussed. This evidence was based on the recollections of one of the DOJ civil rights attorneys who had investigated their voter suppression tactics. Chairman Grassley refused Democrats’ requests for a new hearing so senators could ask him about the new information in person. In early 2018, when the nomination had to go through the committee again in the new year for procedural reasons, Grassley held a vote without a rehearing over Democratic objections.

In so doing, the chairman protected Farr from facing senators in person and answering their questions under oath about his involvement in voter suppression schemes. But the chairman’s responsibility is not to protect nominees; it is to protect the integrity of the federal judiciary.

The 1991 DOJ memo did not come to light until the Washington Post obtained and published it in November 2018, more than 15 months after Farr was nominated. That exemplifies the chairman’s abdication of responsibility: Every member of the Judiciary Committee should have had a copy long ago, before Farr’s confirmation hearing.

Uncovering relevant information about a nominee’s fitness for the bench is the Judiciary Committee’s raison d’être. In this case, the material was a federal government document and perhaps could have been produced in a timely manner had Chairman Grassley simply requested documentation related to the Justice Department’s investigation of the Helms campaign.

Unfortunately, other Trump nominees have also been insufficiently vetted by the Judiciary Committee during the first two years of the Trump administration. For instance, after prematurely scheduled hearings for Jonathan Kobes (Eighth Circuit), John O’Connor (Oklahoma), Brett Talley (Alabama), and Holly Teeter (Kansas), all were determined by the American Bar Association to be unqualified. Unfortunately, committee members were denied the opportunity to question the nominees about their poor evaluations. The Senate is expected to vote on Kobes’s nomination the first week of December.

With Talley, the ABA evaluation was only the tip of the iceberg. After Grassley held his hearing and committee vote, news reports indicated that he had left important information out of his committee questionnaire responses. When asked to identify potential conflicts of interest should he be confirmed, Talley hadn’t disclosed that he was married to the White House Counsel’s chief of staff. He also had failed to disclose thousands of items he’d posted on the internet—specifically, posts he wrote for a University of Alabama fan message board, including disturbing posts in which he defended the KKK and condemned Roe v. Wade. He also responded to the slaughter of young elementary school children in Newtown, CT, by saying that we should “stop being a society of pansies and man up.” A properly functioning Judiciary Committee would have uncovered such information on its own and asked the nominee to explain the omissions.

In some cases, it is a nominee’s statements made at or after the confirmation hearing that merit further vetting and a follow-up hearing. For instance, Louisiana’s Wendy Vitter—whose nomination is pending on the floor—should have to account for testimony she gave at her first hearing that has been shown to be false by video evidence. Similarly, Missouri nominee Stephen Clark—also scheduled for a floor vote—should have to explain his misleading response to a written post-hearing question from Sen. Chris Coons.

Many of President Trump’s nominees have long and disturbing records on a range of issues relevant to their qualifications to be a federal judge. In Farr’s case, no one should have been surprised by the contents of the 1991 DOJ memo: Where there is smoke, there is often fire. The integrity of America’s federal courts depends on the willingness of the Senate Judiciary Committee to thoroughly check for fires when there is smoke.

Hopefully, under the next chairman, the Judiciary Committee will return to its duty to thoroughly vet the men and women nominated for lifetime positions on the nation’s circuit and district courts.