On Wednesday September 29, the full Senate Judiciary Committee will hold a hearing entitled “Texas’ Unconstitutional Abortion Ban and the Role of the Shadow Docket.” We all know about the harmful Texas abortion ban. But just what is the Supreme Court’s “shadow docket” and why is it important to the Texas law?

When the Supreme Court considers a case like Roe v. Wade or Planned Parenthood v. Casey, it decides to review a decision by lower courts, receives extensive legal briefs containing detailed arguments from the parties and friend-of-the court briefs from others, holds public oral arguments in which all justices can ask questions of lawyers from both sides, and issues a detailed written decision explaining which justices voted which way on the case and why. The “shadow docket,” however, is very different.

Sometimes urgent issues are presented to the Court that require decisions more quickly than usual, such as whether to stay an execution while the Court considers constitutional objections to the death penalty in a specific case. This is where the “shadow docket” comes in. In these cases, there is abbreviated briefing, no oral argument, and brief rulings that often do not explain the reasons for the Court’s decisions thoroughly (or at all) and sometimes do not even state which justice voted which way. Such rulings usually uphold what the lower court has done.

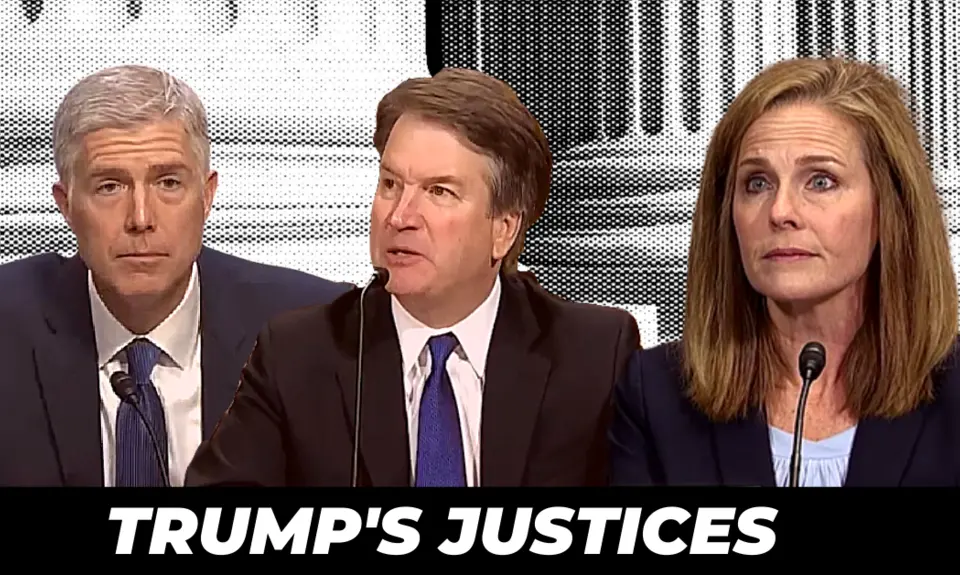

There is no question that there is sometimes a need for the Court to issue temporary orders in some urgent cases through this “shadow docket.” But since Trump justice Gorsuch joined the Court, the use of the “shadow docket” has changed dramatically. During the 16 years when George W. Bush and Barack Obama were president, their administrations asked for emergency relief against lower court decisions only eight times. In contrast, forty-one such rulings were sought by the Trump Administration, concerning controversial subjects ranging from exemptions to COVID-19 rules to the death penalty.

The Trump Administration won almost 70% of these cases, demonstrating what one scholar has called “clear one-sidedness.” In fact, when the Trump Administration enacted its troubling “Remain in Mexico” asylum policy, an unexplained Supreme Court “shadow docket” order blocked a district court order that declared it unconstitutional—presumably because the majority thought the courts should defer to the president on this policy. But that deference disappeared when a Democrat was president: the Court refused to take any action when a Trump judge ordered the Biden Administration to jettison its own approach to the issue and effectively reinstate the Trump policy. No wonder Justice Sotomayor wrote that these peremptory orders have “benefited one litigant” – the Trump Administration – “over all others.”

As the asylum case illustrates, many of the Court’s “shadow docket” rulings have seriously harmed people’s rights, health and safety. For example, several times last year, the Court issued unsigned “shadow docket” orders without full opinions granting special exemptions for religious purposes to restrictions on indoor gatherings to help combat COVID-19. As Justice Kagan wrote in dissent in one case, the majority “defies our caselaw, exceeds our judicial role, and risks worsening the pandemic.”

Now consider the Texas abortion case. In a bit of “shadow docketry” of its own, a Fifth Circuit panel including two Trump judges abruptly cancelled with no explanation a planned district court hearing to consider an injunction against the law, which bans abortions as early as six weeks, before it took effect. The plaintiffs then went to the Supreme Court, which initially failed to act. On the day the law began to shut down abortion clinics throughout the state, the Court issued a 5-4 one-paragraph order denying any relief to the providers and authorizing the law to continue in effect. The majority (including all three Trump justices) did not even explain why they rejected Chief Justice Roberts’ call to temporarily suspend the law so that lower courts and the Supreme Court could fully consider the law with “full briefing and oral argument,” rather than through the hasty “shadow docket” edict.

This is not the way courts are supposed to make important decisions. Federal courts under our Constitution have enormous power to decide people’s rights and even overrule other branches of government, based on what the Court has previously called “reasoned decisions.” It is fundamental to the rule of law and judicial accountability, to the public’s confidence in the judiciary, and to the ability of legislatures and the people to help decide whether to overturn a court’s ruling for courts to explain the basis and reasons for their actions. In too many instances, however, the Trumpified Supreme Court is failing to meet this crucial obligation and issuing edicts rather than reasoned decisions.

No wonder that Justice Kagan’s dissent in the Texas case wrote that the Court’s “shadow-docket decisionmaking” is “every day” becoming “more unreasoned, inconsistent, and impossible to defend.” Even before the Texas events, a House Judiciary Subcommittee hearing revealed support for reform of the “shadow docket” from members of Congress as diverse as Democratic Representative Hank Johnson and Republican Representative Louie Gohmert. The Senate Judiciary Committee’s hearing will hopefully provide more impetus for such efforts.