During Wednesday’s second day of senators’ questioning of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, a number of them honed in on questions Kavanaugh has not answered about his past record concerning presidential power and prerogative. Although Kavanaugh continued to evade or refuse to answer many such questions, the hearing made even clearer than the day before that particularly in light of the major cloud that hangs over our current president, Kavanaugh’s views on presidential power are extremely troubling. Specifically:

With respect to Kavanaugh’s views on accountability for and investigations of presidential misconduct, some questioning concerned his views about whether a president can be criminally investigated and indicted while in office -- a serious concern given our current president. Kavanaugh tried again to claim that it was longstanding Department of Justice policy (which he mischaracterized as “law”) that was his basis for claiming that criminal investigation and indictment could not occur during that time. He did again admit, however, that he previously stated that “[t]he Constitution itself seems to dictate” that “congressional investigation must take place in lieu of criminal investigation when the President is the subject of investigation, and that criminal prosecution can occur only after the President has left office.”

Kavanaugh attempted to explain his previous remarks that U.S. v. Nixon was “wrongly decided” because it took “away the power” of the president to control information in the executive branch. In that case, the Court held that Nixon could be compelled to disclose the Watergate tapes in response to a subpoena by a “subordinate” special prosecutor. Kavanaugh claimed at the hearing that his critical remarks were a sarcastic, rhetorical response to arguments that independent prosecutor Ken Starr’s subpoenas were improper. Sen. Coons was dubious, pointing to a statement by former Watergate prosecutor and moderator of the discussion Phil Lacovara that Kavanaugh’s remarks appeared quite sincere, and reflected his “basic jurisprudential approach since law school.”

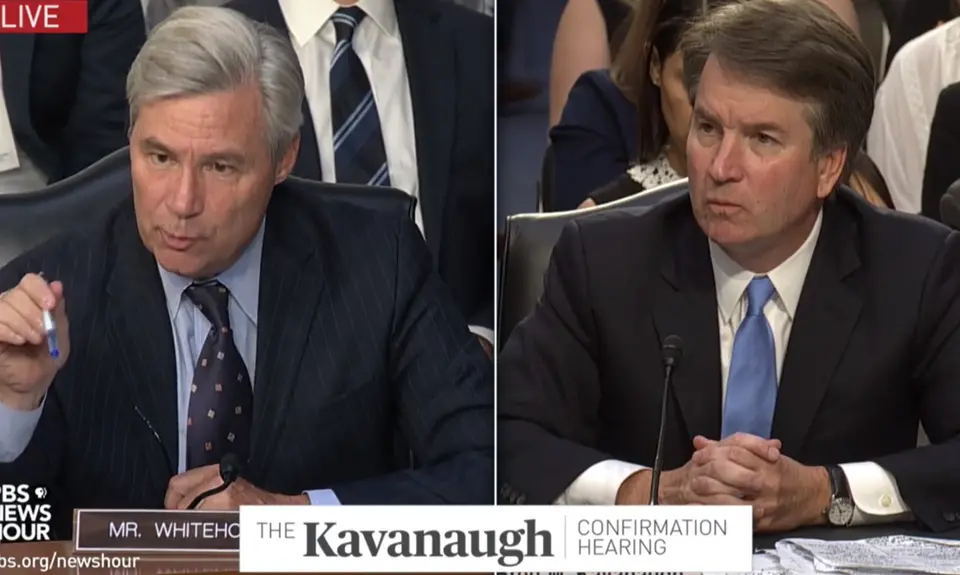

In any event, Senator Whitehouse pointed out that Kavanaugh’s hearing statements on the correctness of Nixon described it as requiring a president to obey a “trial court” subpoena, and asked if Kavanaugh agreed that the same principle would apply to a grand jury subpoena, which is the type that special counsel Robert Mueller would be likely to issue if he seeks documents or testimony from Donald Trump. Kavanaugh refused, opening what Sen. Whitehouse called a broad “escape hatch” for Kavanaugh in a future case.

Coupled with Kavanaugh’s admission the previous day that he has previously said that a president can fire a special counsel like Mueller, it is little wonder that Senators were dubious about whether Kavanaugh would truly have an open mind about legal efforts to hold Trump accountable. Some suggested that Trump may well have chosen Kavanaugh in part because of the judge’s views about legal limits on holding a president accountable. And Kavanaugh again refused to recuse himself from any future case concerning Mueller’s efforts or accountability for Trump. Kavanaugh’s views in this area, as expressed at the hearing and throughout his career, are dangerous for a Supreme Court justice, particularly in the era of Trump.

The second day of questioning also reinforced the serious concerns about Kavanaugh’s record on efforts by Congress to set up independent agencies that he claimed improperly infringe on the president’s power. Sen. Coons in particular focused on Kavanaugh’s dissents in several cases that under the Constitution, a president must be able to fire at will an executive branch official, even when Congress provides by law that firing must be for cause in order to help ensure some independence for the official, as with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Coons pointed out that Kavanaugh’s strong views on this subject apply to the former Independent Counsel law, which Kavanaugh did not deny he thought was unconstitutional, and that those views could also result in Kavanaugh ruling against efforts by Congress to protect a special counsel like Robert Mueller from being fired by at will by a president like Trump. Kavanaugh asserted he would approach such a case with an open mind, but that claim is belied by his record as well as his hearing testimony.

Finally, Kavanaugh’s testimony continued to show that he thinks the courts are limited in their ability to constrain the president. Senators strongly questioned his claim the previous day that his statement in one of his dissents on the Affordable Care Act that a president has the power to “decline to enforce a statute that regulates private individuals when the President deems the statute unconstitutional, even if a court has held or would hold the statute constitutional” simply reflected prosecutorial discretion. Senator Blumenthal, himself a former prosecutor, explained that this was simply not the case, and that Kavanaugh’s view would allow a president to effectively “nullify” a law passed by Congress, like the Affordable Care Act, and would give dangerous “unchecked power” to a president. Kavanaugh again refused to say anything that could be interpreted as critical of President Trump, including declining to agree in general that partisan interference in law enforcement is improper and explicitly declining even the tepid criticism of then-nominee Gorsuch about President Trump’s remarks criticizing the independent judiciary.

Kavanaugh’s two days of testimony make clear that his dangerous views on presidential power should disqualify him from confirmation for a lifetime seat on the Supreme Court.