“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

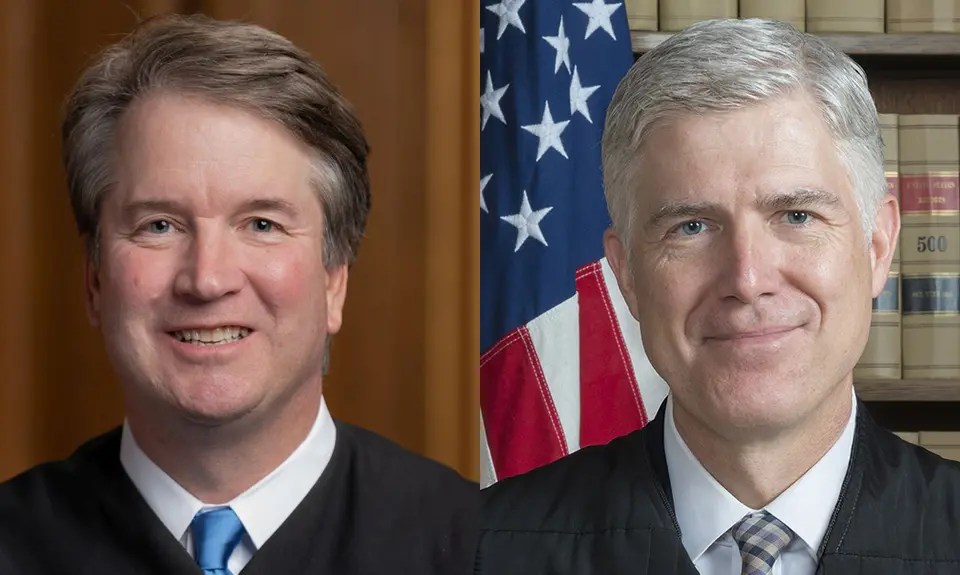

Trump Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a 5-4 Supreme Court opinion, also joined by Trump justice Neil Gorsuch, which made it easier for the Trump administration to deport permanent legal residents who have committed even minor crimes in the U.S. The April 2020 decision is Barton v. Barr.

Andre Martello Barton, a 42-year-old repair shop manager and father of four, had been a “long-time permanent resident” of the U.S. who came from Jamaica in 1989. In 1996, when he was around the age of 18, he was convicted of assault and firearms charges. He attended a “boot camp,” obtained his GED certificate, and “led a law-abiding life for several years.” In the 2000s, he struggled with addiction and was convicted of drug possession. After he completed two drug rehabilitation programs and finished college, he “was never arrested again.” But 10 years after his last arrest, the government detained Barton and sought to deport him because of his prior convictions.

Although an Immigration Judge (IJ) found him deportable, Barton applied for cancellation of removal, citing the multiple years that had passed since he was convicted of these crimes and had lived continuously in the U.S. for at least seven years. The IJ indicated that she would be inclined to grant such cancellation because the record showed that Barton had “clearly rehabilitated” and that his family “relies on him and would suffer hardship” if he were deported. But she accepted the government’s argument that Barton could not qualify for cancellation of removal, because a “stop time” rule in the law stops the seven-years-of-residency time clock when green card holders and longtime legal residents like Barton commit a crime. Both the Eleventh Circuit and the 5-4 Supreme Court majority accepted that interpretation and ruled that Barton could not apply for cancellation of deportation.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor strongly dissented for the Court’s four moderate justices. She explained that Kavanaugh’s interpretation of the law contradicted the “express words of the statute,” the law’s “overall structure,” and “common sense.” She pointed out that Kavanaugh’s interpretation ignored the difference between offenses that render someone “inadmissible,” like Barton’s 1996 assault conviction, and “deportable,” like his firearms and later drug convictions. Because the firearms and drug offenses that did make Barton deportable were not specifically referred to in the "stop time" law, Sotomayor went on, the government had to rely on the assault conviction. That conviction technically did not make Barton deportable but would have rendered him inadmissible.

Sotomayor continued that the problem for the government was that Barton had already been legally admitted at the time of that conviction. That meant that the government’s argument for applying the “stop time” rule to Barton relied on a “paradox” that is contradicted by the statute, and the Court should have determined that he “cannot and should not be considered inadmissible for purposes of the stop-time rule because he has already been admitted to this country” legally, and he should thus have been eligible to apply for cancellation of removal.

Even Kavanaugh’s opinion conceded that deporting a lawful permanent resident is a “wrenching process” with harmful “consequences for family members,” particularly for someone like Barton who has “spent most of his life in the United States.” As a result of Kavanaugh’s opinion, however, that is precisely what has already occurred to Mr. Barton, who is now “effectively barred” from ever rejoining his family in the United States. One estimate is that it could now happen to “thousands” of other immigrants with even “minor” criminal convictions who lawfully live in the U.S.