Sixty-five years ago, the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision ended school segregation and advanced racial equity in our schools for the first time in our country’s history. But despite that promise of equal opportunity in education, racial inequity and racist practices in the classroom persists today — and not surprisingly, the damaging effects on Black and brown children can often last their entire lifetimes.

Every year, dozens of reports of blatantly racist school administrators, educators and substitute teachers make clear how overt racism still persists in our schools. But institutional racism in education is about more than racist teachers: It’s evident in the disparity between the children of color who now make up the majority of public school populations and the overwhelmingly white majority of teachers who educate them.

It’s evident in the lower academic expectations for children of color. It’s evident in educators’ microaggressions, like mispronouncing the names of students or scheduling tests and other important project due dates on religious and cultural holidays, and the white, middle-class values that are often codified into dress codes that prohibit hats and hairstyles favored by communities of color. And it’s perhaps most evident in the racially discriminatory practices against Black and other students of color.

The impact that disciplinary measures have on Black children and other children of color has been studied for more than 40 years. And we know that disciplinary measures like the zero-tolerance policy that criminalizes minor offenses disproportionately affect Black students. As early as preschool, Black children are up to three times more likely to be suspended than white students. And although Black boys face higher rates of school discipline than anyone else, Black girls are up to six times as likely to be suspended as white girls, often for challenging teachers’ biases about traditionally feminine behaviors or for dress code infractions like wearing their hair in braids.

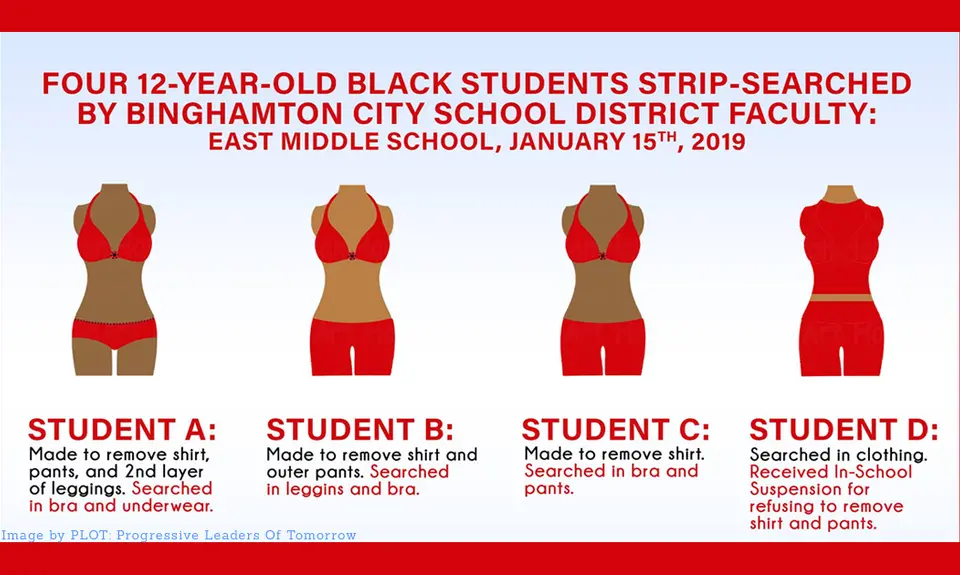

Unfortunately, it can be onerous and sometimes impossible to determine the facts when claims like this arise. In January 2019, after four 12-year old Black girls were allegedly strip searched at a middle school in New York for “hyper and giddy behavior,” the school claimed the search was warranted due to reasonable suspicion of drug possession. But the search was conducted without prior consent of the students’ parents, and no drugs were found. A formal state investigation is currently underway, with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund representing the students’ families.

The facts of this case may still be in dispute, but the concerns are valid. Public schools reflect our democratic commitment to serving and empowering all people equally, but far too often, children of color face discriminatory punishment that many times contributes to the school-to-prison pipeline.

Now is not the time to stand down on students’ civil rights. We need laws and policies to ensure that all children are safe, welcomed and treated fairly in our schools.