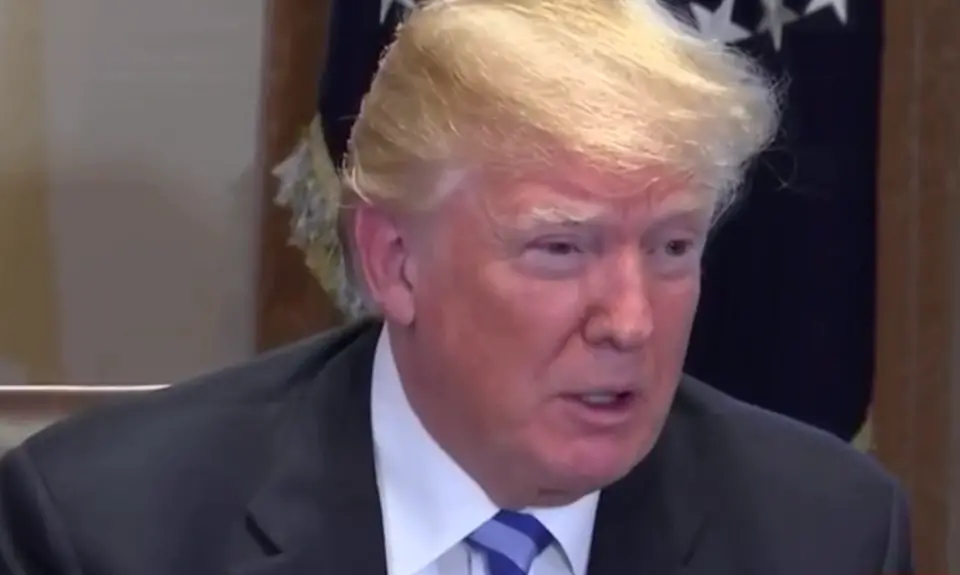

On February 28, the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the National Emergencies Act, which is what President Trump has cited as his authority for declaring a state of emergency along the border so he can keep his racist wall campaign promise. It was led by Rep. Steve Cohen (D-TN). While most of the hearing focused on how Congress can amend the statute to make it far more difficult for a future president to abuse it—and no one spoke out in opposition to fixing the statute—there was naturally discussion of its current misuse.

For instance, one of the witnesses—attorney Stuart Gerson—opened his statement with a call that should transcend party:

I am a lifelong Republican and a devoted constitutional conservative. … It is with first allegiance to the country I have served and to the Constitution that has held it together and allowed it to prosper and become an economic leader and bastion of freedom in the world at large that I come here to explain why the President’s so-called emergency proclamation presents a dangerous violation of the separation of powers that the Framers correctly intended to the core principle of a viable and effective American Constitution.

The Brennan Center’s Elizabeth Goitein provided the committee with insights and recommendations based on a recently completed two-year-long analysis of the legal structure behind national emergencies, a project that she oversaw. She called Trump’s declaration “an unprecedented abuse of the laws governing national emergencies.” Even though the statute does not provide a specific definition:

the word “emergency” is not meaningless. … A basic element of an emergency, in other words, is that the circumstances in question must be unexpected—and must presumably represent a change for the worse, not the better. In that respect, an “emergency” is fundamentally different than a “problem.”

Nayda Alvarez, a homeowner in La Rosita, TX who is fighting the Trump administration’s efforts to take her backyard and build a wall on it, spoke of life on the national border with Mexico:

In more than 40 years of living on the border, I can’t remember ever seeing migrants from Mexico come across my family’s property. To do so, they would have to cross the river, and then they would have to climb up the soft bluff that runs alongside the river at the end of my property. The river and the bluff create a natural barrier on my family’s property, a natural barrier between Mexico and my land in the U.S.

…

I live on a peaceful stretch of property along the river in South Texas, in the United States of America. No drugs, no gangs, no terrorists come across my property. There is no need for a wall on our land. My family should not have to sacrifice our ancestral home to a campaign slogan.

Toward the end of the hearing, she made a comment that gets to what is really behind calls for a wall:

Someone has created hate toward these people.

Indeed.