“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

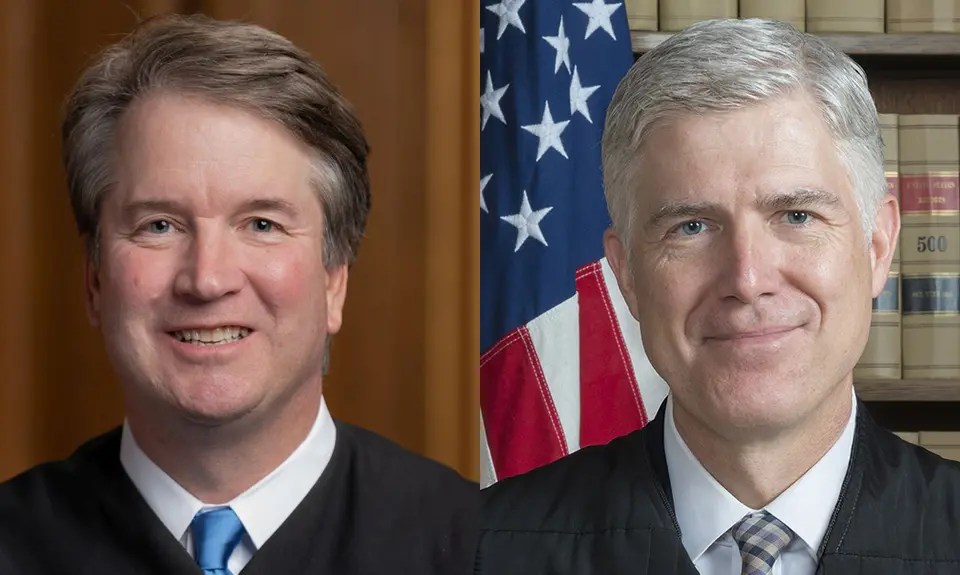

In Kansas v. Garcia in March 2020, Trump Supreme Court justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh made possible a 5-4 ruling that effectively allows states to circumvent immigration laws to set and enforce their own restrictive immigration employment eligibility policies. The four moderate justices dissented, explaining that federal immigration law should have pre-empted the state’s action in the case.

The State of Kansas prosecuted three immigrants – Ramiro Garcia, Donaldo Morales, and Guadalupe Ochoa-Lara – for state law fraud and use of false information because they allegedly used other peoples’ social security numbers in filling out federal and other forms to demonstrate their eligibility for employment and secure jobs. Although all three were convicted, the Kansas Supreme Court reversed the convictions, explaining that under prior Supreme Court decisions, it is the federal government [and not the states] that regulates employment by immigrants and that the state prosecution was pre-empted by the federal Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). The state took the case to the Supreme Court.

In a 5-4 decision by Justice Alito, the Court reversed. Even though the Court ruled in 2012 that IRCA reserves for the federal government the authority to regulate and prosecute fraud committed to show authorization to work in the U.S. under federal immigration law, the majority ruled that IRCA did not pre-empt the state prosecutions in this case. The majority claimed that pursuing alleged state law violations of fraud and use of false information laws was distinct from regulating and enforcing who can work in the U.S. and was permitted.

Writing for himself and the other moderate justices, Justice Breyer strongly dissented. IRCA’s text and structure and previous Court decisions, Breyer explained, make it “clear and manifest” that Congress and the federal government have “occupied at least the narrow field of policing fraud committed to demonstrate federal work authorization.” The Act thus “reserves” to the federal government – and “takes from the States” –the “power to prosecute people for misrepresenting material information” in an attempt to demonstrate that “they are authorized to work in this country.” But that is precisely what the Kansas prosecutions attempted to do, Breyer went on, and should not have been permitted. Such state prosecutions, Breyer, elaborated, undermine Congress’ “deliberate choice” in IRCA “not to impose criminal penalties” on immigrants who seek employment, and to focus instead on enforcement actions against employers who improperly hire them.

The Court’s decision in Kansas thus goes far beyond simply affirming three state criminal convictions. As Justice Breyer put it, the majority opinion “opens a colossal loophole” in federal regulation and enforcement of employment of immigrants. As others have explained, it could allow states to “take immigration policy into their own hands” and “unleash” numerous state and local prosecutors, with inconsistent and potentially harsh results for undocumented immigrants who live and work in the U.S.