This piece originally appeared in the Huffington Post.

In preliminary looks at the record of Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court, reports have already suggested that he is more conservative than Justice Scalia was on the so-called Chevron doctrine. Sounds like a technical issue just for lawyers, right? Not so. In fact, Gorsuch’s radical stance on this issue helps show why his confirmation would jeopardize the health, safety, and rights of all Americans.

The Chevron doctrine is named after a case decided unanimously by the Supreme Court in the 1980s concerning the Chevron energy company. The doctrine, or rule of interpretation that came out of that case, says that courts should generally defer to administrative agencies’ interpretation of laws that Congress has charged them with enforcing—particularly when the laws are ambiguous—unless the regulation or other interpretation is unreasonable. As a result, courts in numerous cases have upheld agency rules that protect health, safety, the environment, and other key subjects. As Ranking House Judiciary Member John Conyers has commented, the Chevron doctrine is crucial to the “ability of federal regulatory agencies to protect public health and safety.”

For example, application of the Chevron doctrine was very important to courts upholding Department of Labor regulations that ensured that more coal miners suffering from black lung disease would receive adequate compensation from coal mining companies. The companies tried to contest the agency’s rule, but relying on the Chevron doctrine, the corporations’ argument was rejected. In another case, industry challenged an important EPA rule that toughened lead-based paint hazard requirements for home renovations under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Relying on cases decided under the Chevron doctrine, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the amended rule. It specifically noted that the amendment would help protect against “dangers to families with young children,” including approximately “23,000 children under age 6.”

But Judge Gorsuch is a firm opponent of the Chevron doctrine. In fact, in a case that did not even specifically raise the issue, he wrote a long concurring opinion, commenting on the opinion that he himself wrote for the court majority, and argued that the Chevron doctrine should essentially be overruled, claiming that it represents “abdication of the judicial duty.” Of course under the Trump administration, federal agencies may well not enact rules that impose reasonable limits on corporations and help consumers. But over the long run, as Rep. Hank Johnson has explained, eliminating the Chevron doctrine would “shield entrenched economic interests from liability and make it harder for agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency to deal with emerging public health threats.” Both Johnson and Conyers spoke in opposition to a House Republican bill that would have attempted through legislation to eliminate the Chevron doctrine.

The fact that Gorsuch’s views accord with those of House Republicans is no surprise. Both are concerned with protecting corporations and not the interests of ordinary people. This is already clear from Gorsuch’s record, and eliminating the Chevron doctrine would do more of the same.

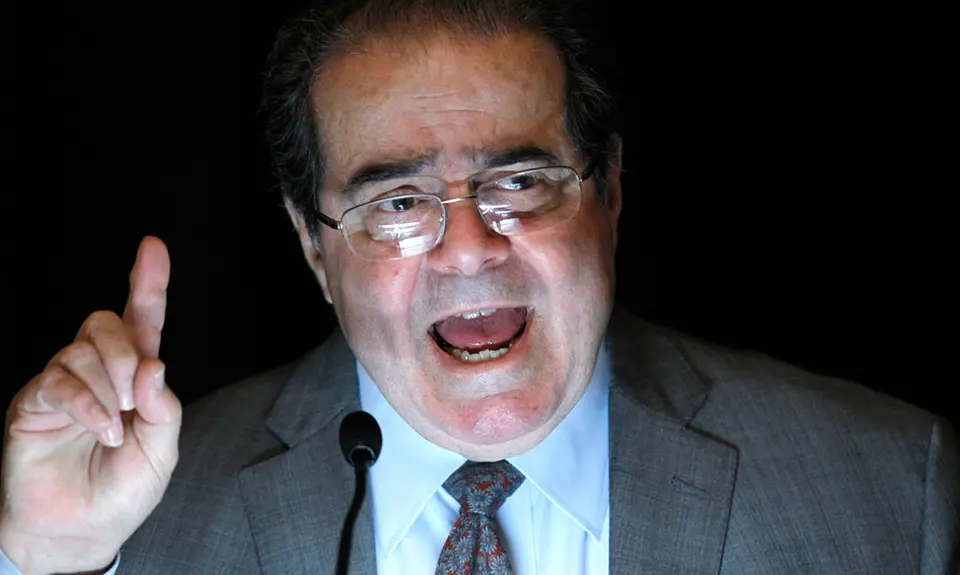

In contrast, while sometimes criticizing specific decisions, Justice Scalia defended the Chevron doctrine, explaining that “[i]n the long run, Chevron will endure and be given its full scope” because it more “accurately reflects the reality of government, and thus more adequately serves its needs.” Thus Judge Gorsuch is clearly to the right of Justice Scalia on this issue, in a way that would ultimately help big business and harm ordinary Americans.

One final point is cause for even more concern. Judge Gorsuch did not write his criticism of the Chevron doctrine in a law review article. Instead, it was in a concurring opinion in a case that did not directly raise the issue, and essentially urged that the doctrine be overruled. This clear willingness as an appeals court judge to urge the overruling of a Supreme Court decision less than 40 years old is extremely troubling for a Supreme Court nominee. Indeed, if he were on the Supreme Court, which actually can overrule its own decisions, he could work towards that result. Gorsuch’s record suggests that other established Supreme Court decisions could also be targets for a Justice Gorsuch, including Roe v. Wade. That’s part of why Gorsuch’s radical views on the Chevron doctrine, to the right of Justice Scalia, help show why he should not be confirmed as our next Supreme Court justice.