Campaign finance reform was once a bipartisan issue. With Koch money flooding into the GOP, those days are gone

This post originally appeared in Salon.

The rising tide of political spending that has swamped Washington in the wake of Citizens United and other controversial Supreme Court rulings may have lifted Republican fortunes across the country and in Washington, but apparently it isn’t enough. Now they are coming back for more.

Congressional Republicans are expected to hide five “policy riders” in the fiscal year 2018 omnibus appropriations bill due for a vote this month that would let churches and charities pour their coffers into partisan pockets, allow parties to spend unlimited funds on ads coordinated with candidates, and make sure the rest of us can’t see what’s going on.

These back-door attempts to eliminate longstanding limits on political spending and prevent any meaningful public disclosure are just the latest signs that Republican politicians have lost their moral compass. Today’s GOP has come to worship at the altar of big money, no matter what the cost to American democracy.

It wasn’t always like this.

In his 1905 address to Congress, Republican President Theodore Roosevelt decried the corruption that resulted from unlimited corporate power and political spending. “[T]he debauchery of politics and business by great dishonest corporations is far worse than any actual material evil they do to the public,” Roosevelt said. “There is no enemy of free government more dangerous and none so insidious as the corruption of the electorate.”

Roosevelt called for sweeping legislation “directed against bribery and corruption in Federal elections” that would bar corporations from spending money to influence elections and require full disclosure of campaign contributions and political expenditures. In response, Congress passed the Tillman Act in 1907 and the Federal Corrupt Practices Act in 2010 to do just that.

>Congress extended the prohibition on political expenditures to unions in 1947, and in 1954 enacted the modern tax code with an amendment by then-Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson — which was accepted without discussion or debate — making it clear that charitable and religious groups that want to enjoy the benefits of tax-exempt status have to sit on the electoral sidelines.

When President Richard Nixon’s political greed — pulling down millions in illegal corporate contributions, taking cases full of cash, and trading milk price supports for a $2 million contribution from the dairy industry — caused a national scandal and made a mockery of campaign finance laws, Congress once again responded with bipartisan reforms.

Every Republican in the U.S. Senate, except for Barry Goldwater and his fellow senator from Arizona, voted for the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA), and it passed on a 334-20 vote in the House. When Congress came back to strengthen the law in 1974, giving us the campaign finance regulatory framework we have today, the bill passed with the support of 15 Republican senators and 137 Republican representatives.

Republican President Gerald Ford’s signing statement for the 1974 FECA amendments praised the “bipartisan spirit” behind the legislation and acknowledged the corrosive effect of big money in politics:

Both the Republican National Committee and the Democratic National Committee have expressed their pleasure with this bill, noting that it allows them to compete fairly. The times demand this legislation. There are certain periods in our Nation's history when it becomes necessary to face up to certain unpleasant truths. We have passed through one of those periods. The unpleasant truth is that big money influence has come to play an unseeming role in our electoral process. This bill will help to right that wrong.

As recently as 2002, the hard-fought McCain-Feingold reforms passed by Congress (the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act), which closed the “soft money” loophole and regulated sham “issue” ads, enjoyed the support of 11 Republican senators and 41 Republican representatives.

Good-government groups like Common Cause — itself founded by a Republican, John Gardner — could count on a strong core of reform-minded Republicans to support such common-sense anti-corruption and disclosure laws in the post-Watergate period. But those days are gone.

“We always used to have bipartisan leadership and bipartisan support in Congress on the reform battles, starting with the Watergate reforms,” said Fred Wertheimer, former president of Common Cause and current president and CEO of Democracy 21. “That changed and Republican opposition hardened after the enactment of BCRA.”

Over the past two decades, Republican leaders and lawyers have fully embraced big money and adopted the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) Second Amendment playbook to argue that even the most sensible campaign-finance rules violate the First Amendment right to free speech. Under Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, House Speaker Paul Ryan, and former GOP vice chairman James Bopp, no regulation is good regulation.

Why the shift? Because today’s Wild West world of political spending gives the more pro-corporate Republican Party a big boost in both federal and state elections.

A 2015 academic study found that Citizens United gave Republicans a significant edge in the 2010 and 2012 elections, and that the outside spending that has soared since Citizens United has heavily favored the GOP. “Dark money overwhelmingly remains a vehicle preferred by pro-GOP operatives,” according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics. “Conservative dark money ma[de] up 76 percent of all reported spending [in 2016] and nearly all unreported ‘issue’ ad spending.” Among the top 10 political spenders in the 2016 elections, seven favored Republicans and accounted for 87 percent of the groups’ combined spending.

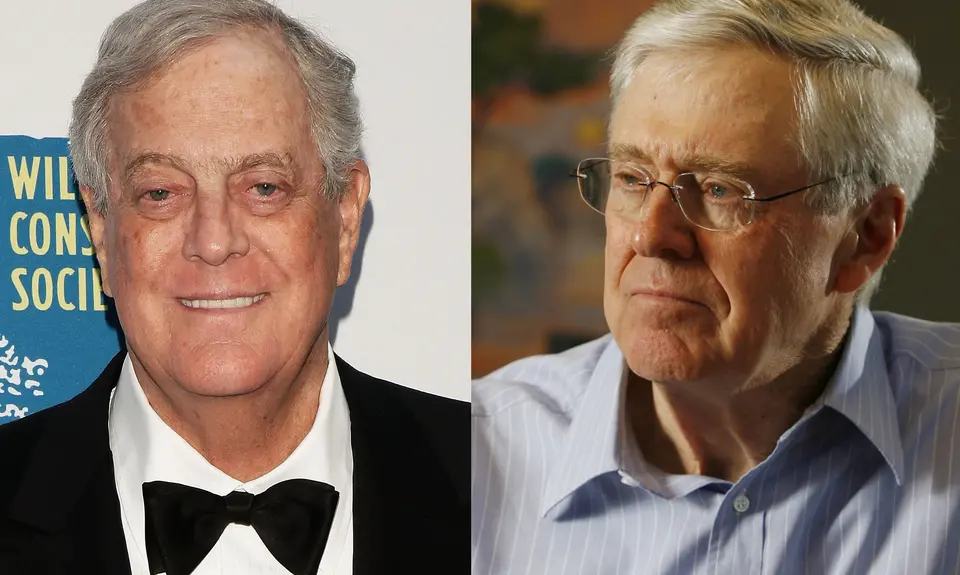

Plutocrats like David and Charles Koch have assembled political operations that rival the traditional political parties, with the GOP as their chief beneficiary. The brothers budgeted to raise and spend $889 million on the 2016 elections, and plan to spend another $400 million on the 2018 midterms. And it’s no secret that Speaker Ryan was handsomely rewarded with a $500,000 contribution to his joint fundraising committee from Charles and Elizabeth Koch, less than two weeks after Congress passed the sweeping tax cuts heavily favored by the Koch machine.

“McConnell and other congressional Republicans see Citizens United and the dangerous advent of super PACs and secret money that followed as creating big financial advantages for the Republicans,” Wertheimer said.

It’s no wonder then that every campaign finance reform bill since McCain-Feingold has run into a brick wall of Republican opposition. McConnell and Bopp have orchestrated a string of court challenges, Republican nominees to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) have effectively blocked any meaningful enforcement, and Republican nominees to the U.S. Supreme Court have toed leadership’s radical First Amendment line.

“The problem is having to file a report at all. To be regulated at all. To be accountable to the government at all,” explained Bopp in a 2008 interview. And when the Supreme Court turned its back on a century of history with its 2010 Citizens United decision, holding that corporations had a First Amendment right to spend unlimited amounts of money to influence elections, Bopp could barely contain his glee.

“We had a 10-year plan to take all this down,” Bopp said. “If we do it right, I think we can pretty well dismantle the entire regulatory regime that is called campaign finance law.” That includes disclosure. “Groups have to be relieved of reporting their donors if lifting the prohibition on their political speech is going to have any meaning,” Bopp said.

That strategy sits in stark opposition to what voters across the spectrum want. A 2015 New York Times/CBS News poll found that more than eight out of 10 voters think money has too much influence in politics, 78 percent want limits on outside spending for political ads and 75 percent support requiring political spenders to disclose where they get their money. There is even strong bipartisan support for campaign reform among former public officials, including Republicans across the country.

But for the present-day GOP leadership, the partisan math behind deregulated political spending clearly trumps public opinion. And the lure of such political riches likely accounts for McConnell's near-religious zeal against any kind of campaign reform. Even for him, it wasn’t always this way. Back in 1987, the Kentucky senator proposed a constitutional amendment to allow Congress to limit independent expenditures, saying it was needed to “restrict the power of special interest PACs, stop the flow of all soft money, [and] keep wealthy individuals from buying political office.” In 2000, he said, “Virtually everybody in the Senate is in favor of enhanced disclosure, greater disclosure, that’s hardly a controversial subject.”

No more. In 2012, McConnell led a filibuster against the DISCLOSE Act and denounced what he called “government-compelled disclosure of contributions to all grassroots groups” as a “dangerous” tactic aimed at exposing government “critics to harassment and intimidation.” And in 2014, McConnell testified against the Democracy for All Amendment — which was aimed at undoing the damage of decisions like Citizens United — claiming that those in power would use constitutional authority to limit spending to “suppress speech that is critical of them” and “pick losers and winners” in politics.

The giant chasm between what cash-dependent politicians and their patrons want on the one hand, and what voters want on the other, explains the underhanded approach Republicans are taking this year to cement their big-money advantage. They would never be able to get their wish list for unlimited and undisclosed political spending passed in the light of day, so they are hiding it in a must-pass appropriations bill.

Through poison pill policy riders, McConnell, Ryan and their congressional colleagues are doing their level best to use their legislative leverage to repeal the 1954 Johnson Amendment to unleash billions more in dark money from churches and charities, gut current anti-coordination rules, keep political spending by government contractors and corporations secret, and prevent the IRS from coming up with rules to deal with the post-Citizens United misuse of nonprofit organizations for political gain.

Sure, 85 percent of voters want “fundamental changes” or a “complet[e] rebuild” of campaign finance regulations. And sure, thousands of faith leaders and nonprofits have said “no” to politicizing tax-exempt groups. But unless rank-and-file Republicans start listening to their constituents and rediscover their Rooseveltian roots, we’re about to get more big money influence in politics, not less.