“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties.

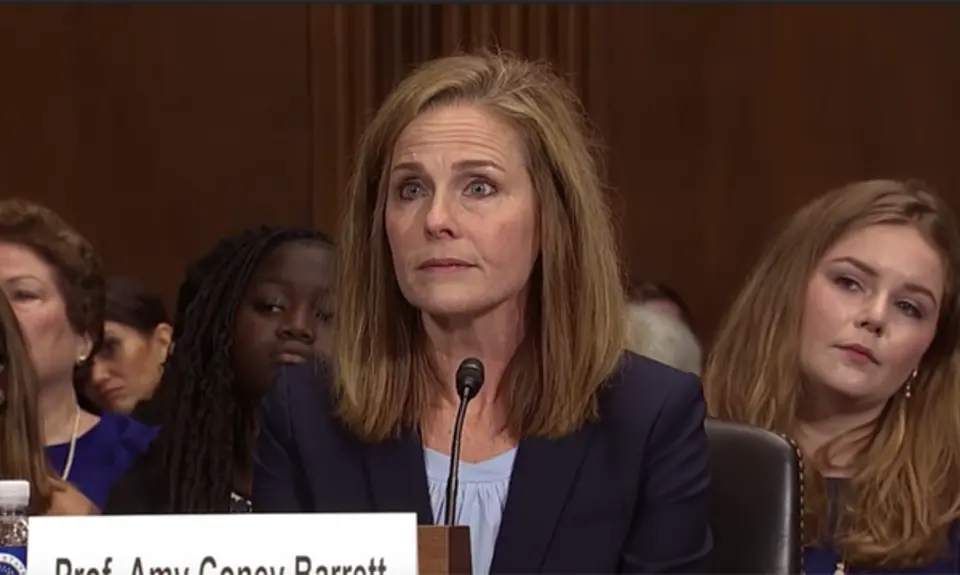

In June 2018, our “Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” series reported on a dissent by Seventh Circuit judge Amy Coney Barrett that would have denied a defendant in a criminal case his constitutional right to counsel. Unfortunately, in December, the panel’s ruling protecting the right to counsel was reversed by the circuit en banc in an opinion authored by another Trump judge, Amy St. Eve. She was joined by both of Trump’s other nominees on the circuit (Barrett and Michael Scudder), as well as by all of the judges nominated by Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. The case was Schmidt v. Foster.

Scott Schmidt was on trial for murder and wanted to present an important defense. Ordinarily, the defendant’s attorney would present his case to the judge explaining why this defense was available to his client. But in this case, the trial judge held a closed session before the trial to question the defendant and—critically—ordered that his lawyer not participate. Based on that session, the trial judge ruled that Schmidt could not present his chosen defense at trial, and he was convicted of first-degree murder. A three-judge panel had recognized in 2018 that this unconstitutionally denied Schmidt the effective assistance of counsel, a decision that Barrett dissented from.

St. Eve’s December 2018 opinion overruled the panel. The new majority criticized the trial judge but ruled that there was no clearly established Supreme Court precedent on the matter. Having unmoored itself from clearly controlling law, the majority upheld the conviction because (the judges wrote) there wasn’t enough deprivation of counsel to be unconstitutional. For instance, even though the lawyer was prohibited from speaking during Schmidt’s conversation with the judge, he was nevertheless in the room. Not only that, but the judge allowed them to consult with each other beforehand. In addition, the trial judge’s questions were based on filings that the lawyer had written. There had also been a recess during which Schmidt could consult with his lawyer before having to answer more of the judge’s questions without being able to get help from his lawyer. Given these facts, St. Eve wrote that the court couldn’t presume that Schmidt had been prejudiced by what happened.

Writing for the dissenting judges, Judge David Hamilton sharply criticized the majority for focusing on such factors:

The majority, not the Supreme Court, has introduced here the notion that only a “complete” denial of counsel requires a presumption of prejudice.

Hamilton explained that this is a straightforward case of a constitutional violation:

If the judge had simply said that he wanted to hear what the accused had to say without any counsel even present, I could not have imagined, at least before this case, that any court in the United States would find such interrogation acceptable without a valid waiver of counsel by Schmidt himself.

The only difference here is that Schmidt's lawyer was physically present in the room, but the judge might as well have gagged him: he ordered the lawyer not to "participate" in this critical stage of the prosecution. I don't see a constitutional difference between an absent lawyer and a silenced lawyer.

Unfortunately for Schmidt and for the Bill of Rights, Trump’s judges in the Seventh Circuit—Amy St. Eve, Amy Coney Barrett, and Michael Scudder—carried the day. (Trump nominee Michael Brennan did not participate in the case.)