“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties.

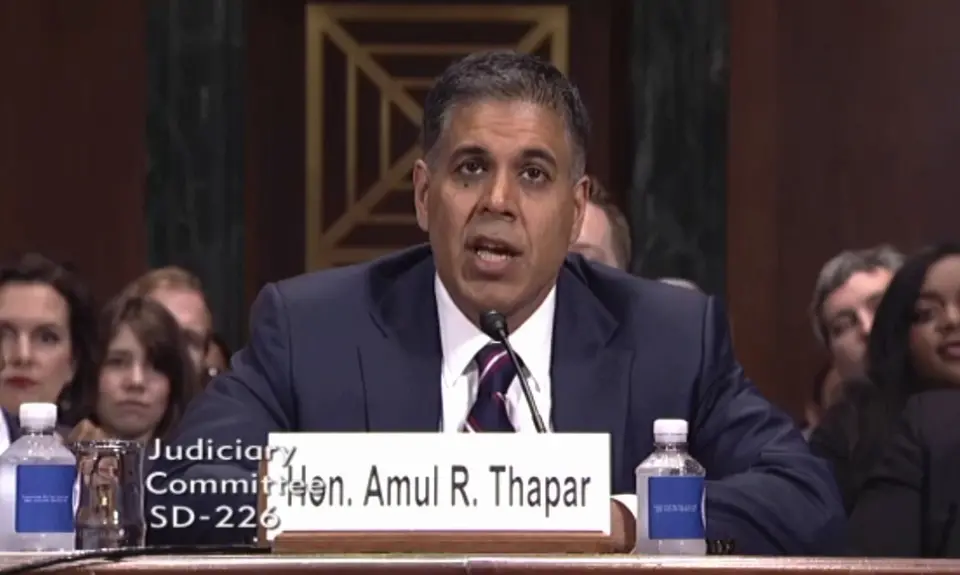

If Trump Sixth Circuit Judge Amul Thapar’s dissent in a September case called Morgan v. Fairfield County became law, police would have more leeway to invade your property and look for illegal activities without a warrant.

In general, absent exigent circumstances, law enforcement officials without a search warrant cannot legally invade your privacy at home any more than any other stranger can. Under the Fourth Amendment, they can knock on the front door and ask to speak with you or to conduct a search, and you have the constitutional right to say no and close your door, just as you can with any other stranger.

In Fairfield County, Ohio, the sheriff’s department required that if a law enforcement official performs such a “knock and talk,” other law enforcement must surround the house for extra protection and to prevent anyone inside from running away. In this case, they were positioned just five to seven feet away from Neil Morgan and Anita Graf’s house, on the sides and in their backyard.

The first police unit member knocked at the front door, Morgan opened it and said he did not want to talk, and then closed the door. But then an officer in the backyard said he can see some marijuana plants on the second floor balcony. So the first unit member forced his way through the front door, brought the residents outside, and prevented them from leaving while his colleagues got a warrant to search the house, based on the plants on the balcony.

The majority of a three-judge panel on the Sixth Circuit recognized that the county’s policy made it liable for a constitutional violation:

The right to be free of unwarranted search and seizure would be of little practical value if the State’s agents could stand in a side garden and trawl for evidence with impunity. And the right to privacy of the home at the very core of the Fourth Amendment would be significantly diminished if the police—unable to enter the house—could walk around the house and observe one's most intimate and private moments through the windows.

Judge Thapar, President Trump’s first circuit court nominee, disagreed. He wrote that the word “search” as understood by the framers was limited to “investigating a suspect's property with the goal of finding something,” regardless of whether there was a reasonable expectation of privacy. He wrote that the county’s policy was intended to block potential exits and prevent anyone from leaving, not to have the police there to search for anything. So, he concluded, intruding into Morgan and Graf’s backyard and looking up at their balcony was not a “search.” And since it wasn’t a search, the county policy was constitutional: police did not need a warrant to surround a person’s house just a few feet from the structure and peer inside.

Thapar criticized long-established Supreme Court precedent incorporating people’s reasonable expectation of privacy into the constitutional analysis:

A “search” under the Fourth Amendment is thus easier to identify when we are faithful to the ordinary and original meaning of the term, and the concept is broader than the Court's current jurisprudence contemplates.

Yet in this case, Thapar’s redefinition gives much narrower protection, not broader. The authority that Thapar would grant could clearly lead to serious abuses by police.