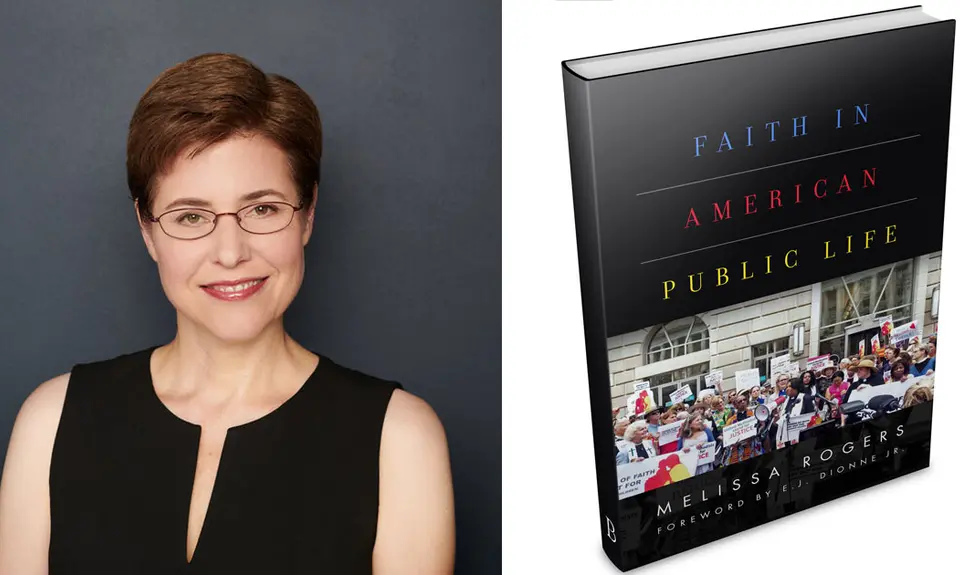

At a time when President Trump, other public officials, and many others are continuing to use religion to divide America and achieve political gain, Melissa Rogers’ new book, Faith in American Public Life, makes a very positive contribution. Rogers, now a visiting professor at Wake Forest University, has worked on religious liberty issues for more than twenty years. This includes serving as a special assistant to President Obama and executive director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships. She previously served as the general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, where others at People For the American Way and I first got the chance to work with her.

Rogers is an example of what I have considered a “traditional” Baptist on the issue of church-state separation. She believes strongly in the right to free exercise of religion and protecting that right against improper government interference. Harkening back to early Baptists in America who were distinct religious minorities, however, she also believes strongly in the separation of church and state, which properly prevents the government from promoting religion. That principle, combined with protecting free exercise, is critical in protecting religious liberty for all and “ensuring that religion and government are meaningfully independent,” as Rogers writes.

Based on that framework, Rogers’ book carefully reviews the history of crucial Supreme Court cases concerning religious liberty in America, and then goes on to consider specific controversies on the subject, right through the first several years of the Trump administration. Chapters discuss the role of religion at the White House; respecting the rights of religious and non-religious people to engage in policy and politics; prohibiting government from endorsing religion; protecting “nongovernmental” religious speech; partnerships between government and faith-based and community organizations to help “serve people in need”; ensuring that government funds support “secular, not religious, activities”; the thorny issue of religious exemptions and accommodations concerning anti-discrimination and other laws; religious liberty in employment and at the workplace; and religious discrimination and hate crimes. Each chapter discusses Rogers’ own experience at the Obama White House, as well as events much earlier and a bit later, and includes specific recommendations for public officials and others.

As E.J. Dionne has written, Rogers’ book “combines a passionate commitment to the religious liberty guarantees in the First Amendment” with a principled and “practical approach to how we can live together in peace and respect each other’s rights.” The book is written to appeal to the public broadly, as well as to lawyers and scholars. For those of us who have long been concerned about these issues, as well as for those just now learning about religion in America, the book is both valuable and essential.