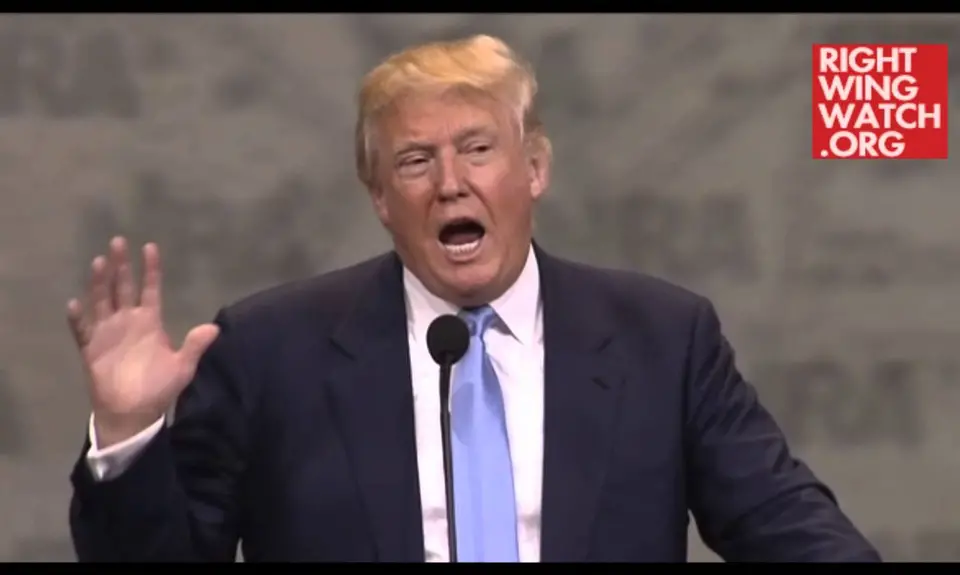

In a particularly appalling moment in his appalling presidential campaign, Donald Trump said that women who have an abortion should, once the procedure is outlawed, face “some form of punishment.” Trump later attempted to backtrack on his comments, then denied having backtracked, then bragged about all the compliments he supposedly received for his original statement.

Trump eventually came around to the position—after briefly saying he wanted to leave abortion laws the way they are— that while he supports criminal punishments for abortion providers he would not want to impose them on women who obtain the procedure. Once abortion is recriminalized in America, Trump said, women who want an abortion “would perhaps go to illegal places.”

Now, apparently not just content with bringing back-alley abortions back to America, Trump now wants more women overseas to face the prospect of having unsafe abortions.

Trump announced today that he will reinstate the global gag rule, which, according to the Guttmacher Institute, disqualifies “foreign nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from eligibility for U.S. family planning assistance if they used non-U.S. funds to provide abortion services, counseling or referrals, or to engage in advocacy within their own countries to liberalize abortion-related policies.” Democratic presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama rescinded the rule, also known as the Mexico City Policy, while every Republican president since Ronald Reagan has enforced it.

While federal law already prohibits the U.S. from using money on abortion services overseas, the global gag rule cripples family planning groups around the world.

“When enforced, it has led to the closing of some of the developing world’s most effective family planning programs,” the Guttmacher Institute notes, pointing out that rates of abortion actually increase as a result of the policy.

One Stanford University study found that when the global gag rule was in effect, the abortion rate increased to a greater extent in countries in sub-Saharan Africa that relied more heavily on family planning and reproductive health programs than in countries with less exposure to them:

Our study found robust empirical patterns suggesting that the Mexico City Policy is associated with increases in abortion rates in sub-Saharan African countries. Although we are unable to draw definitive conclusions about the underlying cause of this increase, the complex interrelationships between family planning services and abortion may be involved. In particular, if women consider abortion as a way to prevent unwanted births, then policies curtailing the activities of organizations that provide modern contraceptives may inadvertently lead to an increase in the abortion rate.

A study by the International Food Policy Research Institute found a significant increase in unintended pregnancies and abortion among women in Ghana after “policy-induced budget shortfalls reportedly forced NGOs to cut rural outreach services, reducing the availability of contraceptives in rural areas.”

The Guttmacher Institute points out that more women face the prospect of unsafe abortions as a result of the policy:

In reality, attempts to stop abortion through restrictive laws—or by withholding family planning aid—can never eliminate abortion, because those methods do not eliminate women’s need for abortion. The abortion rates in Africa and Latin America—regions where the procedure is mostly illegal—are 29 and 32 per 1,000 women of reproductive age, respectively; in contrast, the rate in Western Europe—where abortion is lawful on broad grounds—is 12 per 1,000. Where abortion is permitted on broad legal grounds, it is generally much safer than where it is highly restricted. The vast majority of abortions are sought by women in the world’s poorest countries, and most of those abortions—about 20 million—are unsafe (i.e., performed by an untrained person or in an environment that does not meet minimum medical standards, or both). According to the World Health Organization, unsafe abortion remains a leading cause of maternal death.

Undermining access to family planning services ultimately hurts women by denying them the tools they need to prevent unwanted pregnancies—and, therefore, to avert abortions. Placing legal barriers between women’s reproductive health needs and desires and their access to safe abortion services only leads to unsafe abortion. History has shown that the gag rule has done and can do nothing to alter this reality, except to exacerbate it.

The group also notes that the global gag rule has implications for HIV/AIDS prevention programs, as it hampers the work of NGOs that distribute condoms.

While Trump may not achieve his wish of outlawing abortion in America and punishing those involved in abortion care, he is already determined to punish women overseas with the prospect of losing health care access—while doing nothing to reduce the abortion rate.