A Right Wing Watch Investigation

ON THE FIRST Tuesday in April, as the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic was becoming all too real, Americans got a scary glimpse of what Election Day in November might look like if the virus were still spreading. We also got a big, loud, ugly preview of the 2020 voting wars.

The state of Wisconsin had no business holding an election on April 7. Sixteen other states had bumped their primary dates back, hoping to give election officials time to adjust to the drastic new conditions and allow more voters to cast their ballots safely by mail. Governor Tony Evers had issued a statewide stay-at-home order. In Milwaukee alone, at least 51 people had already died from the new coronavirus. And so many poll workers were refusing to show up that the city, home to Wisconsin’s largest concentration of voters of color, would be hard-pressed to open even a handful of polling places, never mind the usual 180. “We are over our heads in chaos,” Neil Albrecht, Milwaukee’s election chief, told The Guardian a few days before the voting was slated to start.

We are over our heads in chaos.

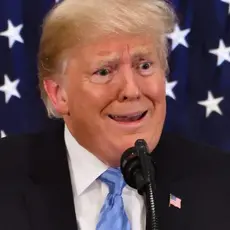

Evers, a Democrat, tried to push the election date to May 23 and send mail ballots to all registered Wisconsinites. But he waited too late. By the time Evers called the state legislature into emergency session the week before the polls were to open, asking legislators to approve the delay and green-light an all-mail ballot, President Donald Trump and his right-wing amen chorus had begun to paint voting by mail not as a public-health necessity during a pandemic, but instead as a Democratic plot to “rig” the 2020 elections—“perhaps the worst of all the scams perpetrated through the COVID nightmare,” as Trump fan Laura Ingraham put it to viewers of her Fox News Channel show.

In addition to the Democratic presidential primary that was to take place on that day, there was also an election for a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

“A lot of people cheat with mail-in voting,” the president said on April 4. “In Wisconsin what happened is I, through social media, put out a very strong endorsement of a Republican conservative judge, who’s an excellent brilliant judge, he’s a justice. And I hear what happened is his poll numbers went through the roof, and because of that, I think they delayed the election.”

So Wisconsin Republicans forced the show to go on. The Republican leaders of the state Assembly and Senate both gaveled in their special sessions, then gaveled them out within seconds. When the governor responded by issuing an executive order to delay the primary, the majority-Republican state Supreme Court stayed it on the night before the election.

Voting went smoothly enough in the state’s smaller counties and towns, where white Republicans predominate and polling places had no lines. But in the cities, it was an unholy mess. Lines were so long in Green Bay that some people couldn’t vote till after midnight. In Milwaukee, the scene was downright eerie; some poll workers wore makeshift hazmat suits fashioned from plastic bags. National Guard troops, hastily called in to serve as poll workers, dashed around with plastic bottles of disinfectant spray, wiping things down between voters. Local firefighters passed out hand sanitizer to the thousands who waited for hours in lines that stretched for blocks, far past the trail of orange traffic cones that had been set up to keep folks six feet apart. Outside Washington High School, one waiting voter, Jennifer Taft, summed it all up perfectly, holding up a hand-lettered sign reading: “THIS IS RIDICULOUS.”

Milwaukee, Wisc. - April 7, 2020: Milwaukee voters waiting in line for hours to cast their ballots in Wisconsin's Spring election during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photo: Henry C. Jorgenson / Shutterstock.com

“I’m disgusted,” Taft told a local reporter. “I requested an absentee ballot almost three weeks ago and never got it. I have a father dying from lung disease, and I have to risk my life and his just to exercise my right to vote.”

Statewide, overall turnout was higher than expected. Even in that compressed time period, 1.1 million of Wisconsin’s 3.3 million voters had sent in absentee ballots—five times the number of voters who did so in the 2016 primary. And when the votes were all tallied six days later, the Democratic Supreme Court challenger had won easily, giving the lie to Trump’s theory that Evers wanted to delay the election to prevent a GOP victory.

But the Republicans’ efforts to sew confusion and long lines in the cities had worked in certain ways: In Milwaukee, which saw historically low Black turnout in 2016 after a strict new Voter ID law went into effect, the primary vote was half what it had been four years earlier. “It was voter suppression on steroids,” said Democratic National Committee Chair Tom Perez. “They tried to steal the election.”

I have to risk my life just to exercise my right to vote.

The mail balloting hadn’t gone smoothly, either: Nearly 12,000 voters who’d requested absentee ballots, like Jennifer Taft, never got them. Three tubs full of absentee ballots that never reached voters were found in a mail center outside Milwaukee. And 23,000 absentee ballots sent in by voters—more than Trump’s margin of victory in the state in 2016—had been disqualified for technical problems. Here as elsewhere, Republican lawmakers had made the process as complicated and time-consuming as possible to keep mail voting down, including a requirement that a witness sign every ballot. Voters’ signatures had to match the signatures on file with the state; as in other states, it’s left to election volunteers and staffers, not handwriting experts, to decide whether the signatures match. Thousands of votes were tossed on this subjective basis. (In June, after the delayed New York primary, 30,000 votes from Brooklyn, one-quarter of the total, would be tossed out for similar reasons.)

The threat of robust turnout figures posed by mail-in voting had fully stirred the right-wing propaganda machine by now—and it had given them a fresh new story to tell about what they claimed was the looming threat of mass left-wing “voter fraud.” The same day Wisconsin’s primary results were announced, an apparently new group called the Honest Elections Project aired an Orwellian TV and digital ad across the country—a six-figure buy—casting what happened in Wisconsin as Democrats’ “brazen attempt to manipulate the election system for partisan advantage by exploiting the coronavirus pandemic.” It was, the narrator intoned, a sign of election-rigging to come: “The facts about the Wisconsin election: Record absentee voting. Five times more than 2016. Democrats didn’t think they could win so they tried lawsuits, changing the rules, even canceling the election. They create chaos. It’s wrong.”

The Honest Elections Project turned out to be a legal alias for the Judicial Education Project, a powerful dark-money PAC funded by the Donors Trust, a nonprofit donor-advised fund often referred to as the “dark money ATM” of the right, with such heavy-hitting benefactors as billionaire Charles Koch and the (Betsy) DeVos family. It was the brainchild of Leonard Leo, a Trump confidant who was instrumental in the choice and confirmations of the president’s Supreme Court nominees, and it would soon begin filing lawsuits seeking to block the expansion of remote voting, and other pandemic-inspired election reforms—using the same lead attorney, longtime Washington litigator William Consovoy, as the Trump campaign.

Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch, a litigious right-wing group that sues to effect voter-roll purges.

At least three other lavishly funded far-right groups—Judicial Watch, the Public Interest Legal Foundation, and True the Vote—are also combining legal challenges with propaganda efforts designed to discredit, and disable, remote voting for November. The Republican National Committee issued a statement this spring promising to devote at least $20 million to such lawsuits as well. The messages they’re all promoting are identical to Trump’s rhetoric about the dangers of mail-in balloting and the Democrats’ purportedly cynical promotion of it to allegedly rig the election. Their combined resources and firepower adds up to the biggest coordinated effort to suppress votes in history. Until this year, battles over voting rules were mostly waged by Republican state lawmakers and right-wing legal firms not quite acceptable to the mainstream, cheered on by talk-radio shouters and extremist websites like The Gateway Pundit and Breitbart.

“You used to have these small-time, right-wing operations,” Mark Elias, a top Democratic litigator who’s working on several ongoing lawsuits, told The Washington Post in June. “Because Donald Trump has normalized all these crackpot theories about voter fraud, they’ve all now joined forces under the banner of the legitimate Republican establishment.”

All they want, they say, are the same old “fair” and “normal” elections that Trump keeps calling for. But the president, characteristically, had already given away the game before the Wisconsin primary lit the right wing on fire. On “Fox & Friends” during the week before that primary from hell, he’d warned the friendly hosts what would happen if voting by mail were allowed to metastasize: “You’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”

Gallows humor from artist Mike Licht regarding Wisconsin's April 7, during-the-pandemic, in-person Spring election. via Flickr creative commons

THE CRUSADE TO suppress votes in the 2020 election began long before COVID-19 existed, and long before the pandemic led to a popular clamor for more voting by mail. Three weeks after his razor-thin victory in the Electoral College, still irked at hearing about Hillary Clinton’s edge in the popular vote, President-elect Trump issued a tweetstorm citing right-wing conspiracy theories. His chief claim, often to be repeated: “I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.”

On stage at the 2017 Conservative Political Action Committee convention three months later, Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch, backed up Trump’s claims. “The left would have you believe that we have about 43 million aliens in this country, both lawful and unlawfully present,” he said. “And none of them vote!” The activists in the audience cheered and chuckled. “You know, under the Obama administration, they opposed Voter ID; they opposed the idea of even asking someone whether they were a citizen before they register to vote,” Fitton went on to say. “Why would you be opposed to that, other than maybe wanting to steal elections when necessary?” Cue applause.

Fitton also seconded Trump’s call for a “federal investigation into voter fraud,” promising that it would be “the most significant civil rights investigation in a generation,” because, he said, “We’re on the side of civil rights. We’re on the side of the civil rights of Americans who potentially are having their votes stolen from them by the thousands, if not millions, by illegal votes.” Getting the findings to back up those assertions would be a breeze, he promised. “It’s easy to figure out where there’s voter fraud,” Fitton said, “and obviously that’s why the leftist voters are screaming, because they’re afraid their gig is up.”

Not quite, as it transpired. That “investigation” was launched in May 2017, when Trump made appointments to his newly concocted Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, which included top vote-suppression specialists Kris Kobach, the former Kansas secretary of state and anti-immigration zealot, and Hans von Spakovsky of the Heritage Foundation. But it didn’t prove so easy to find hard proof of the massive fraud they’d long been claiming. After eight months of trying, the commissioners dug up only scattered cases drawn from media reports, and the president disbanded the effort.

This is a pretext for blocking voices they do not want to hear.

But voter-suppression is now an industry unto itself, and Judicial Watch and its peers didn’t skip a beat. Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, Judicial Watch and PILF sent 248 letters to state and local election officials across the country, threatening lawsuits if they didn’t undertake massive, aggressive “purges” of their voter rolls. “Your jurisdiction is in apparent violation of Section 8 of the National Voter Registration Act,” the letters claimed. The NVRA, known as the “Motor Voter Act,” was passed in 1993 to “expand voting opportunities” in various ways, including offering registration at driver’s license offices. It also required local elections offices to undertake “uniform, non-discriminatory maintenance” of their registration rolls, striking those who’d become ineligible—by dying, going to prison, or moving out of state.

Under previous administrations, the Justice Department monitored these purges and sometimes stepped in when they became overzealous and were clearly targeting voters of color. “The rationale of removing voters from the rolls to protect against fraud is nonsensical,” Stacey Abrams, who founded the voting-rights group Fair Fight after narrowly losing the Georgia governor’s race in 2018, told Mother Jones earlier this year. “This is a pretext for blocking voices they do not want to hear.”

The letters contained legal threats, but their primary purpose was to stoke publicity about voter fraud—and to raise the profiles of Fitton and J. Christian Adams, a former Department of Justice official who heads PILF and served on the ill-fated Election Integrity Commission. Adams is best known as the DOJ attorney who promoted a 2008 “voter intimidation” case against two members of a group that dubbed itself the New Black Panthers. On Election Day 2008, the two stationed themselves outside a predominantly white polling place in Philadelphia, one of them holding a nightstick. When Obama’s Justice Department declined to press charges, Adams loudly resigned and wrote a book called “Injustice: Exposing the Racial Agenda of the Obama Justice Department.” In lawsuits and legal threats targeting jurisdictions with large numbers of non-white voters, Adams first launched suits via the American Civil Rights Union (a right-wing group that fancies itself to be the analog to the American Civil Liberties Union), and then with PILF.

“The rationale of removing voters from the rolls to protect against fraud is nonsensical,” says Stacey Abrams. “This is a pretext for blocking voices they do not want to hear.” (Photo of Abrams on election night 2018 from Abrams' Facebook page.)

Judicial Watch and PILF got a few big victories out of their threats and lawsuits, in 2018 and again last year. In 2018, the Supreme Court upheld a Judicial Watch settlement agreement with Ohio and allowed a massive voter purge—a decision that opened the floodgates for more of the same, permitting states to strike voters who haven’t voted in recent elections. As 2020 began, counties in California and Kentucky were busy removing close to 2 million voters; ditto, Allegheny County, one of the largest Pennsylvania counties carried by Hillary Clinton in 2016. In three other large Clinton-voting Pennsylvania counties Judicial Watch dragged into court this year, the group claimed an almost comically high number of “ineligible” voters—800,000 in all, which would amount to more than 65 percent of all registered voters in the counties. “We 100-percent dispute the claims,” Secretary of the Commonwealth Kathy Boockvar, who was also sued, told state senators.

Most of this year’s election lawsuits are related to COVID-19—or, more precisely, they target attempts by states and municipalities to make voting easier and safer during the pandemic. The number of these cases is staggering: More than 200 were still percolating through the courts in mid-August. Many have been brought by the Trump campaign, the Republican National Committee, Judicial Watch, PILF, and the Honest Elections Project, all of whom have the same agenda: Keep voting restrictions in place. Three more states have switched to all-mail elections this year: California, Nevada, and Vermont. When lawmakers in Nevada, where Trump lost by just 27,000 votes in 2016, approved all-mail voting in a special session on the first Sunday of August, Trump called it “an illegal late-night coup” on Twitter, with the promise, “See you in court!” Two days later, still fuming, he posted a tweet falsely stating that voting by mail would mean a “Rigged Election.” It became the first tweet flagged by Twitter as untrue. The same day, the Republican National Committee, the Trump campaign, and Nevada Republican Party all filed suit against Nevada.

In most states, election officials and lawmakers have simply tried to ease restrictions that can make absentee voting difficult or confusing: early deadlines for requesting ballots, Election Day deadlines for having them returned or postmarked, requirements that witnesses or notaries sign the ballots, strictly limited forms of acceptable ID. In some cases, the question is whether vulnerability to COVID-19 counts as an “excuse” for needing a mail ballot. (Most states already allow no-excuse absentee voting, but a few—like emerging battleground Texas—do not.)

Graphic from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Justin Levitt, a Loyola University law professor who tracks all these cases, has not detected a pattern in the decisions. But as he’s noted, it’s already a win for right-wing organizations and the Republicans to keep elections officials tied up in courts—and election rules in a state of suspended uncertainty as states try, with chronically inadequate funding, to manage an election during a pandemic. “My usual election-cycle comment is that we’re trying to find enough duct tape to cover the holes in the bucket,” Levitt said recently. “This time, we’re trying to make the bucket out of duct tape.”

The uncertainty created by the lawsuits, combined with the disinformation about voting that will be plastered all over social media this fall, creates an indirect but powerful form of voter suppression in itself. “Voter suppression is a combination of things,” says Georgia state Rep. and voting-rights advocate Renitta Shannon. “It’s a chipping away of people either not being able to vote, or thinking it will be a major hassle. When people have a question about whether their vote is going to be counted, that [becomes] a reason not to vote.”

ON JUNE 5, Tom Fitton and J. Christian Adams were both invited to testify at a U.S. House hearing on “Protecting the Right to Vote During the COVID-19 Crisis.” It was another sign of how formerly fringe right-wing conspiracies had become thoroughly mainstreamed in Trump’s GOP. And it provided another platform to spread the falsehood that Democrats were using the pandemic to make real their fraudulent dreams. “It is now about five months until Election Day,” Fitton testified, “and the pandemic’s infection curve has flattened. Insisting now on all-mail-ballot elections seems less like a response to a health crisis and more like a partisan application of the immortal words of Rahm Emanuel: ‘Never let a good crisis go to waste.’”

Fitton’s coronavirus predictions would soon be disproved, but the notion of Democrats using mail ballots to commit grand theft in 2020—“using COVID to defraud the American people,” as Trump expressed it on the first night of the Republican National Convention—remains the central deceit of the right’s propaganda campaign. “The Democrats have cooked this thing up,” Rush Limbaugh bellowed in August, “because they don’t feel confident that they can win in a traditionally fair and normal election.”

J. Christian Adams, president and general counsel of the Public Interest Legal Foundation in 2019 screencap.

In many places, the relative unfamiliarity of mail voting is a boon to the fear-mongering. And with folks on the right having been treated to years’ worth of “voter fraud” talk, they’d been conditioned to take it seriously. “When they talk about voter fraud,” says Tomas Lopez, executive director of the progressive group Democracy North Carolina, “they’re talking about race, of course. They’re lamenting the fact that those people get a vote.”

Across platforms—Fox News, talk radio, social media, presidential briefings—the narrative being served up about mail voting has been remarkably consistent in all its main plot points. It’s almost as if Judicial Watch teamed with the Trump campaign and sent out a bullet-point memo, which kicks off with “stealing and rigging” and proceeds, from there, to the following talking points:

-

- Even more “illegals” get to vote. “Here’s a shocking things for your audience to consider,” senior Trump adviser Stephen Miller, architect of the immigration policy that caged children at the U.S.-Mexico border, said in August on “Fox & Friends.” “Nobody who mails in a ballot has their identity confirmed; nobody checks to see if they’re even a U.S. citizen. Think about that. Any foreign national—talk about foreign election interference—can mail in a ballot, and nobody even verifies if they’re a citizen of the United States of America.” (In reality, every state verifies the identity of the person requesting the mail-in ballot.)

This summer, Judicial Watch bought at least 263 ads on Facebook (cost: $210,000) to drive home the same spurious claim delivered by Miller on Fox News. According to a tally from Media Matters for America, 144 of the ads, which were full of disinformation about “voter fraud,” claimed that “illegal aliens are voting,” while 119 got more specific, claiming that “25% of noncitizens are registered to vote.”

-

- Ballots Are On the Loose. On May 1, Trump retweeted Mollie Hemingway, a writer for The Federalist, a right-wing publication, who had some “news” that sounded startling: “Nearly one in five of all absentee and mail-in-ballots between 2012 and 2018 remain unaccounted for, according to data from the federal Election Assistance Commission,” she wrote. Hemingway drew her figures from a new and scholarly looking report by PILF—J. Christian Adams’ organization—which claimed that 28 million absentee ballots had “gone missing” in recent election cycles. Those ballots represent a golden opportunity for mass-scale fraud, Adams said in a statement accompanying the PILF report—“28 million opportunties for someone to cheat.”

The “missing ballots” meme spread like wildfire. But as voting-rights advocates (and logical thinkers) pointed out, the ballots aren’t just floating around, waiting for noncitizens and Democrats to scoop them up and send them in; they simply hadn’t been returned by the voters who got them. Twelve million of the “loose” ballots, as they’re also called, had been sent by election officials in Colorado, Oregon, and Washington state, where everyone who registers automatically receives one. About 30 percent of voters in those states typically don’t return their ballots in a given election. “Where are they now?” said Paul Gronke, a Reed College professor who runs the Early Voting Information Center, of the so-called “missing” ballots. “Most likely, in landfills.”

-

- Democrats Are Harvesting Those Loose Ballots. Expect to hear several earfuls about “ballot harvesting” between now and November. It’s the hip, scary-sounding new catchphrase for voter-fraudsters, though the practice it describes is a routine feature of absentee voting in more than half the states: Basically, it just means that a third party can collect someone’s vote in its sealed envelope and hand-deliver it to an election office. The laws are meant to help people who live at great distances from polling places without transportation, or who are sick or shut in, to cast a vote. In March, Trump’s own ballot in the Florida primary was “harvested”—he gave it to an (unknown) third party, who delivered it directly to an elections office in Palm Beach. Nonetheless, as he tweeted on April 14, we must “GET RID OF BALLOT HARVESTING, IT IS RAMPANT WITH FRAUD.”

Democratic workers sometimes organize “community collections,” leading right-wing pundits to peddle fantastical visions of thugs pounding on doors and demanding people’s blank ballots for harvesting. The proof? Well, in Paterson, N.J., this spring, a postal employee noticed something odd in a local post office five days before an all-mail primary: 347 completed ballots bundled together. They were part of a scheme for which four perpetrators, including one city council member, have all been charged with fraud. Amid the controversy, Paterson’s election board disqualified 19 percent of the ballots in the primary—which, trickling up from Gateway Pundit, a conspiracy theory website, to the West Wing, served as evidence of the fraudulent potential of “harvesting.” “Look at Patterson[sic], N.J.,” Trump tweeted. “20% of vote was corrupted!” In fact, election officials said that most of the uncounted ballots were tossed out for the usual technical reasons—mainly for signatures that didn’t appear to match those on file. The only example of large-scale ballot harvesting occurred in a North Carolina congressional race in the 2018 midterms. It was organized by a paid GOP operative who’s facing both state and federal charges.

President Donald J. Trump addresses his remarks during a news conference Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room of the White House. Official White House Photo by Joyce N. Boghosian

"THIS IS GOING TO BE the greatest election disaster in history,” Trump promised reporters in the middle of yet another rant against vote-by-mail in August. He failed to mention how hard he and his right-wing allies were fighting to make his apocalyptic predictions about the election come true—or how much his prospects for victory may hinge on it.

The right’s doomsaying about chaos and fraud at the polls have definitely penetrated the national consciousness. In August, a Pew poll found that nearly half of registered U.S. voters expect to “have difficulties casting a ballot” this year. That might not sound surprising—but it’s a sea change from 2018, when 85 percent expected voting to be “easy.”

When it comes to mail voting in particular, however, it’s only Republicans who are moved by the propaganda. When Pew asked Trump supporters how they planned to vote, 80 percent said they’d do it in person, while just 17 percent would vote by mail. By contrast, most Biden supporters—58 percent—said they’d be voting remotely.

Given those results, it’s no surprise that, in the 2020 battleground states, Democrats are outpacing Republicans in absentee ballot requests. Far more, in fact. Four years ago in Florida, Democrats requested 6,000 more absentee ballots than Republicans; by the end of August this year, ballot requests by Democrats had surpassed those from Republicans by 600,000. In North Carolina, where absentee voting has always been sparse, 177,000 Democrats had asked for ballots compared to 50,000 Republicans. “Everybody’s up,” said Michael Bitzer, a politics professor at Catawba College. “It’s just that Democrats and unaffiliated are through the roof, and Republicans are not even on the second floor.”

This disparity, which is consistent in other battleground states, has saner Republican officials and activists deeply worried. What if the anti-mail campaign ends up backfiring, and suppressing their votes? And with the virus likely to still be raging come November, will GOP voters—seniors, in particular—actually take the risk to show up in person to vote? “What the president is doing when he keeps saying that this mail-in balloting thing is fraudulent, he’s scaring our own voters from using a legit way to cast your ballot,” Rohn Bishop, chair of the Fond du Lac County GOP in Wisconsin, told USA Today. “We’re kind of hurting ourselves.” When he tries to talk up absentee voting to fellow Republicans, Bishop said, he gets a lot of flak that he’s “ignoring voter fraud.” It’s not easy to argue when the Republican president keeps calling vote-by-mail “the greatest scam in history.”

The weird thing, said Bishop and other Republican state leaders, is that while the president continues to slam mail voting on a daily basis, the Trump campaign and RNC have told them to promote it. “I’m out there pushing it at the request of the campaign, because they asked me [to] do that,” said Lawrence Tabas, chair of the Republican Party in Pennsylvania, which Trump carried by less than 1 percent in 2016—and where Democrats have made 68 percent of all mail-ballot requests, while Republicans requested just 24 percent. “And then the president is publicly opposed to it,” Tabas added. “Let’s put it this way; it’s made my job more challenging.” The Pennsylvania GOP website urges Republicans to “Vote Safe: By mail. From home.”

GOP voters in California also heard that “safe, from home” message before they voted in this spring’s primary—from two of Trump’s family members, no less. Both daughter-in-law Lara Trump and Donald Jr. recorded robocalls in April urging mail votes for a Republican congressional candidate in a special election. “Nancy Pelosi and liberal Democrats are counting on you to sit on the sidelines this election, but you can prove them wrong,” Lara Trump said in one call. “You can safely and securely vote for Mike Garcia by returning your mail-in ballot by May 12.”

Both Lara Trump and Donald Jr. recorded robocalls in April urging mail votes for a Republican congressional candidate in a special election.

One major group on the right, Americans for Prosperity, is flexing its considerable muscle to counter the president’s message and urge right-wing voters to take advantage of either early or absentee voting this fall. Tim Phillips, president of the “grasstops” group, which underwrote the Tea Party movement, told Politico this spring that AFP “is absolutely going to up the percentage of dollars that go into absentee and early voting.” The group, which raked in $83 million in donations in 2018, has plenty to spend. It plans to target conservative voters in dozens of competitive congressional districts.

Tim Phillips, president, Americans For Prosperity, appears on the CBS News program "Red & Blue" on April 18, 2018.

But Judicial Watch, PILF, the Honest Elections Project, and allied groups like True the Vote—which is recruiting ex-Navy SEALs to serve as GOP poll-watchers on Nov. 3—are delivering a contrary message: It’s perfectly safe to vote in person. “Don’t let the left scare you from voting on Election Day,” Tom Fitton said on a Judicial Watch podcast on July 31. The same message continues to blast out on conservative media. “If people can go to Home Depot and distance six feet,” Fox host Jeanine Pirro said this summer, “why can’t they go to the voting booth and distance six feet?”

Is there a coherent strategy here, somehow? Do the clashing messages make any strategic sense? Perhaps not. But some political observers suspect that Trump is setting up a way to delegitimize the results in November. If more Republicans do turn out in person, their votes will be among those tallied first—creating a chance that Trump may lead on election night, even if only half of the total vote, or less, is counted by then. In that event, Jamelle Bouie wrote this summer in his New York Times column, “There’s no mystery about what Donald Trump intends to do… . First, he’ll claim victory. Then, having spent most of the year denouncing vote-by-mail as corrupt, he’ll demand that authorities stop counting mail-in and absentee ballots. He’ll have a team of lawyers challenging courts and ballots across the country.”

It’s certainly plausible. Just as in 2016, Trump has refused to say he’ll accept the results—unless, that is, they show him winning. “You don’t know until you see,” he said this summer on Fox News. “It depends. I think mail-in voting is going to rig the election, I really do.”

In November 2018, when the Republican candidates for governor and senator in Florida held leads on election night that began to dissipate as the vote-counting continued, Trump telegraphed what he might say this November: “The Florida election should be called in favor of Rick Scott and Ron DeSantis in that large numbers of new ballots showed up out of nowhere, and many ballots are missing or forged,” he tweeted. “An honest vote count is no longer possible—ballots massively infected. Must go with Election Night!”

Attorney General William Barr has indicated that the Department of Justice would have Trump’s back if he tries to shut down the count. “I think the people who want to experiment with different ways of voting right now … are playing with fire and are grossly irresponsible,” Barr told Fox News’ Mark Levin in August. Sounding more like a Judicial Watch attorney than the attorney general of the United States, Barr called it “scary” that “most of those mailings go to a lot of addresses where the people no longer live. They’re misdirected. And I think they will create a situation—they could easily create a situation where there’s going to be a contested election.”

That is chilling to hear. It stirs up nightmare visions of Florida 2000 but on a national scale—and in a year that’s already been full of unrest. Realistically, though, it’s also a far-fetched strategy born of desperation. And there’s a much rosier scenario that is just as plausible as Bouie’s, if not more so.

Say this election proves to be less apocalyptic than Trump and the right are hoping—and say Trump is clearly a loser on election night. The president’s defeat, and the pandemic-inspired rise of mail voting, could begin to unravel the elaborate system of barriers to voting that Republicans have been erecting over the past decade. If Democrats retake a majority in the U.S. Senate, the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act will surely be one of the first measures to pass, restoring protections and federal oversight to elections. And if Republicans lose control of state houses they captured (which they are poised to do in several battleground states), Democratic majorities can begin to reverse the race-based voting restrictions that the GOP has been cooking up with relentless creativity since the Tea Party insurrection lifted them to unprecedented power in Congress and the states.

“What we’ve had is the 21st century equivalent of the Mississippi Plan of 1890,” says Carol Anderson, the Emory University historian and best-selling author of One Person, One Vote. That “plan” was the template for other states to “redeem” white supremacy after Reconstruction by disenfranchising Black men all over again, through tactics like poll taxes, literacy tests, and violent intimidation. The 2010s were eerily similar. “It’s been legislative evil genius,” Anderson says. “And so Jim Crow.”

Anderson is a serious historian, so she’ll make no predictions. But there is at least a fair chance that the latest manifestation of the Republicans’ long and fraudulent voter-fraud campaign—the demonizing of remote-voting during a pandemic—will backfire on them in a lasting way. The hollering won’t die down, of course; Trump himself will make sure of that. The voter-suppression industry—the Judicial Watches, the PILFs, the Honest Elections Projects—won’t disappear. Chief Justice John Roberts won’t suddenly start deciding in favor of voting rights. But the more Americans grow accustomed to voting by mail, and the more they keep demanding that it be made easier and more reliable, the harder their votes will be to suppress or toss out. Trump is right, after all, about one thing: Wherever remote voting becomes routine, turnout soars. And we all know who loses then.