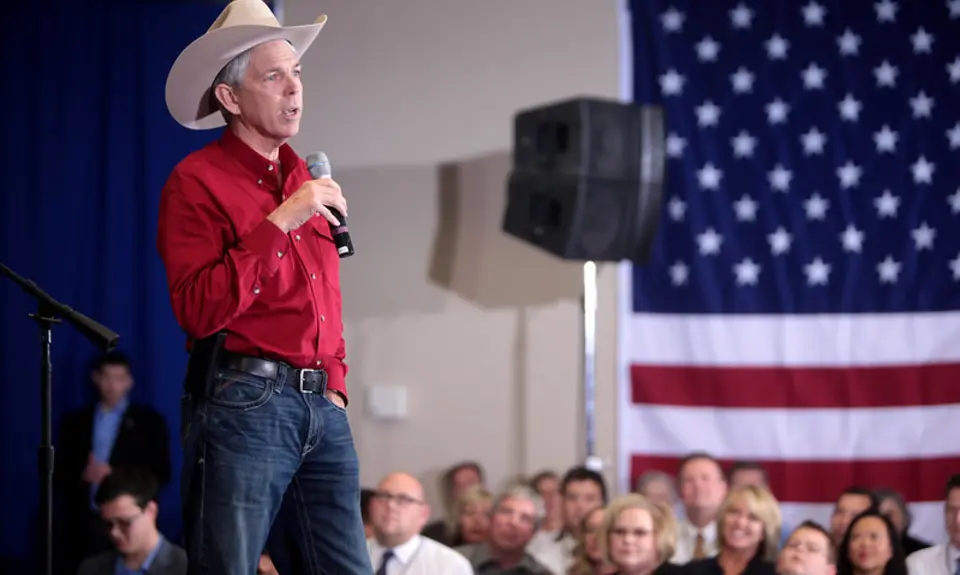

When the Family Research Council held its annual "Pray, Vote, Stand" summit last week, Christian nationalist pseudo-historian David Barton was given a prime speaking slot, along with dozens of right-wing pastors, activists, commentators, and members of Congress.

While introducing Barton, FRC's president Tony Perkins declared that what critics deride as Christian nationalism is simply true American history, and he credited Barton for having "done more than anyone else to help Americans, and Christians in particular, to know their history"—a history that Perkins claimed has intentionally been "hidden" by mainstream historians.

Perkins is correct in noting that nobody has been as influential as Barton in convincing millions of Americans that the United States was founded to be an explicitly Christian nation. And that is a problem, given that Barton’s misuse and misrepresentation of both American history and the Bible have been well-documented.

Barton's willingness to misrepresent history and scripture to promote his right-wing political agenda was on display when he spoke at Calvary Church in Moline, Illinois, last Wednesday as part of the Faith Wins voter mobilization effort.

One of Barton's favorite methods of convincing his audience that America was founded as a Christian nation is to assert that Americans of the founding era were so deeply knowledgeable about the Bible that they referenced it continuously in their writings and speeches. The problem today, Barton insists, is that modern Christians are ignorant of both history and scripture and are thus incapable of recognizing the fact that our founding documents are chock-full of Bible quotes.

The irony of this assertion is that it relies on the very ignorance Barton decries in order to be effective, as anyone willing to look into the claims Barton makes will inevitably find that he is lying.

While speaking at Calvary Church, Barton trotted out a new example of this technique, when he claimed that first- and second-grade students attending public schools in New Jersey in the early 1800s were required to memorize large portions of the Bible as part of their curriculum.

It's interesting to go back in those early records and see what was being taught in the schools. For example, let me take you to some early schools. I want to take in New Jersey. And in this case, I'm just going to choose 1816 [in] New Jersey. They're going to show you what happens with first- and second-graders in New Jersey. Here's what they say. It says, 'All the scholars of the first and second classes commit to memory portions of the New Testament or Psalms, a lesson of the Catechism, several hymns, and the text of the preceding Sabbath.' Everybody in public school in New Jersey, if you're in first and second grade, this is what you're getting memorize. And by the way, what are the texts of the preceding Sabbath? That means whatever Pastor Tim talked about on Sunday, we're going to memorize those Bible verses; so whatever verses he referenced, we're going to memorize. A public school is doing this? Yes, absolutely. This is what public schools did.

As we all know, some kids are sharper than other kids, and they talked about one of the kids that was really sharp. They said, 'One of the scholars has committed to memory the Book of John, and the first 30 Psalms, together with 119th Psalm.' A [student] in first and second grade memorized the Gospel of John, 30 Psalms, and Psalm 119. He was really sharp. The rest of the kids weren't quite so sharp. Here's what it said about the rest of them, 'The majority have committed to memory the Gospel of John.' The average kid has memorized the Gospel of John. Everybody does that in first and second grade, but we got one kid that added 30 chapters out of Psalms and Psalm 119. Really? Common for first and second grade is everybody memorizes the Gospel of John? Maybe one in 1,000 Christians today has memorized the Gospel of John, and that was first and second grade stuff back then.

Thanks to the quotations Barton cited, we were able to track down the document he used in making this claim. It was a report from the board of directors of the Free School Association of Elizabeth-Town published in a periodical called The Christian Herald and, predictably, Barton was blatantly misrepresenting it.

The first thing one notices upon reading the report is that the reference to "the scholars of the first and second classes" does not refer to what today would be called first and second graders. The report explicitly states students are "divided into seven classes" based upon their reading and writing abilities and that "most of the children in the fifth class were unable to read when they entered school."

It is unlikely that first- and second-graders were memorizing entire books of the Bible, as Barton claimed, while fifth-graders were unable to read.

But more importantly, the document further reveals that this was not a public school at all, as Barton claimed, but rather a Sunday school.

As it notes, the students were "taught on the Lord's day, immediately after the conclusion of public worship in the afternoon."

In fact, the document itself confirms that these students were enrolled in Sunday school when it notes the existence of "two other Sunday schools" that were not under the board's control.

As author James J. Gigantino II explained in his book, "The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865," the Free School Association of Elizabeth-Town grew out of the so-called "Sabbath school" movement, in which "schools sponsored by churches and private donors took over black education and continued white paternalistic control over it. These schools were led by white teachers and administrators, focused primarily on reading, writing, and basic mathematics, and taught biblical reading knowledge and prayer to instill religious and moral lessons in their students."

From "Church of the Founding Fathers of New Jersey: A History," a book chronicling the history of the First Presbyterian Church Elizabeth, it is clear that these were indeed Sunday schools set up by Rev. John McDowell, the author of the document that Barton cited.

One of the great and enduring achievements of the church during John McDowell's ministry was the founding of the Sunday School. The first Sunday Schools in America were founded about 1805 in Boston and Philadelphia. The movement spread rapidly to other cities of the country, but not always with success. In many places, the schools were virtually forced upon the church members and the communities, and after a brief trial period, they were abandoned.

Reverend McDowell decided that the idea of founding a Sunday School was good, and used a very cautious approach in establishing the first school in this area. He enlisted the support of his Session, and then contacted Reverend John Churchill Rudd, Rector of St. John's Church, and Reverend Thomas Morrell, minister of the Methodist Church, to ask their support. Both men became convinced that the purpose of the proposed Sunday School was good, and the three clergymen began to "sound out" their congregations on the idea. The groundwork was laid in 1812 and 1813.

By the spring of 1814, enough parents were convinced that religious training for their children was a desirable thing, so the school was opened, meeting in the Public Academy located on the north-east corner of the church property. Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Methodist children met together, and were taught by the three ministers, at the first sessions. At once the school was a success, and at the end of the first month, it was necessary to open a second school for the Negro children of the town. The colored Sunday School was taught by a student who was studying theology with Reverend McDowell. An organization calling itself the Free School Association of Elizabethtown was set up to handle the administration of the Sunday Schools, with Miss Maria Smith as superintendent.

According to professor John Fea, chair of the History Department at Messiah University and author of "Was America Founded as a Christian Nation?," a search of American newspapers and periodicals published in the early 1800s "clearly show that this is a Sunday School."

"This once again shows that Barton fails to understand the larger context of the periods from which he cherry-picks his facts," Fea told Right Wing Watch. "It would have taken Barton less than an hour, with the historical databases available to professional historians, or even just a search on Google Books, for him to dig up multiple primary sources showing that the 'Free School Association of Elizabeth-Town' was, in fact, a Sunday School. In fact, 'public schools' as we know them today did not exist in the early decades of the 19th century. This is the kind of sloppy work—void of any concept of context or change over time—that has characterized Barton's entire career as a Christian Right activist who raids the past for something useful to help him advance his political agenda in the present."

We need your help. Every day, Right Wing Watch exposes extremism to help the public, activists, and journalists understand the strategies and tactics of anti-democratic forces—and respond to an increasingly aggressive and authoritarian far-right movement. The threat is growing, but our resources are not. Any size contribution—or a small monthly donation—will help us continue our work and become more effective at disrupting the ideologies, people, and organizations that threaten our freedom and democracy. Please make an investment in Right Wing Watch’s defense of the values we share.