When white nationalist Jason Kessler announced he would convene a rally in Washington, D.C.’s Lafayette Park, the logistics and operational experts in at least four different law enforcement agencies must have jumped into gear with gusto. The plans must have been elaborate, evidenced by lines of police arrayed at every juncture of the racists’ journey from the Metro stop at Vienna, Virginia, to the one in the heart of D.C., next to George Washington University. Police forces involved included those of Fairfax County, Virginia, the District of Columbia, the National Park Service and Metro.

It was at Kessler’s beckoning, after all, that white racists of every stripe and insignia descended on Charlottesville a year ago today for a rally of the same name: “Unite the Right.” Last year, Kessler’s rally, which was to have featured alt-right star Richard Spencer and former Knights of the Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke as speakers, never got off the ground.

Before the 2017 event could commence, the state police shut it down by calling a state of emergency, but then allowed armed hatemongers to roam the streets. A lot of people got hurt, mostly at the hands of the white supremacists. Thirty people were injured in one assault alone—the apparent terrorist car attack by reported neo-Nazi James Alex Fields Jr. that also killed counter-protester Heather Heyer. So, on Sunday, law enforcement in the District of Columbia and Fairfax County, Virginia, were taking no chances. Jason Kessler’s First Amendment rights would be protected with an army of thousands, while the right of the press to practice freely under the same amendment took a few lumps.

At the Vienna station, which had been designated by Kessler as the meeting place for his rally contingent, police closed the gates of one of the station entrances, even to media, and kept reporters and photographers from the station interior at the remaining entrance. Police officers would not say for sure whether media would be permitted to ride the same Metro train as the rally-goers.

When white supremacists finally emerged from a parking garage to make a grand entrance past human chains of police in day-glo vests, there were all of two dozen or so of rally-goers, led by Kessler, wearing a suit. His followers wore polo shirts or plaid button-downs; some carried American flags. At least two wore helmets emblazoned with the URL of the New Jersey European Heritage Association.

A robust but police-compliant crowd of protesters stood behind law enforcement’s lines of separation, booing and shouting as the extremists made their way into the station with a law-enforcement escort.

On the station platform, a train designated “Special” awaited the racists, who were given priority boarding. It was only after they descended the escalator to the platform that police broke lines to let in the media, who found themselves blocked off—by another line of police—from entering the train car occupied by 20 or so attendees of Kessler’s “white civil rights” rally.

In the train car directly behind the white-supremacists-only car, photographers tried to shoot pictures of Kessler and his crew through two sets of cloudy windows, while a police officer stood guard at the door that led to their specially guarded means of conveyance into the heart of the nation’s capital.

It was only a few days before that members of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 689, the union representing rank-and-file Metro workers, leaked the transit agency’s plans for the white nationalists’ special train car(s) to the media. (Anticipating more rally-goers, the original plan called for three special cars.)

“More than 80% of Local 689’s membership is people of color, the very people that the Ku Klux Klan and other white nationalist groups have killed, harassed and violated,” Local 689 leaders said in a statement provided to ThinkProgress. “The union has declared that it will not play a role in their special accommodation.”

Subsequently, Metro Board Chair Jack Evans made a statement suggesting that that the agency had backed off that plan, but on the afternoon of the August 12 rally, it appeared to be in full force.

Media were again shooed away by police when the train arrived at its final destination, Foggy Bottom station. The cars bearing media and others were emptied first, with police prodding reporters and videographers to exit the station, while the extremists waited in their heavily guarded special car.

When they finally left the station, they were greeted by hundreds of protesters and people who work in the neighborhood with jeers and boos and shouted F-bombs. “Nazis go home!” some shouted.

The Kessler crew then began to march down 23rd Street with an extravagant police escort that entailed dozens of vehicles—cops on bikes and motorcylces, in cars and even vans rented from Enterprise. Photographers and videographers who followed the marchers were reportedly shoved around by police. (I didn’t personally see this because I couldn’t get close enough to the tiny band of marchers.) In fact, few in the media got anywhere near the hate-rallyers, affording the white nationalists a glut of attention with no accountability.

Kessler's white nationalists got quite the welcome when they exited the Foggy Bottom station. Media kept far from them. pic.twitter.com/szmkpBo91a

— Adele M. Stan (@AddieStan) August 12, 2018

Mediaite’s Caleb Ecarma reported that, once at the mic in Lafayette Park, Kessler allowed that his rally was a bust. Among other things, he blamed in-fighting on the far right.

This is largely right, at least if you consider the mutual contempt for Kessler among disparate and ideologically diverse racist groups a form of in-fighting. It would be a mistake to view Kessler’s bust as a reflection of weakness on the right. The Charlottesville melee, especially the apparent terrorist attack by Fields, reflected poorly on the right’s stars. The violent chaos that filled the streets on that day was not the image that leaders such as David Duke and Richard Spencer sought to project.

Just the night before, Spencer had led his polo-and-khaki-clad legions in a torchlit march of cinematic scope to the exquisite campus of University of Virginia, no doubt imagining it unfold to a soundtrack by Depeche Mode—an aesthetic like that of an ‘80s New York dance club, but with Nazis. And while Spencer’s audacious UVA demonstration ended with the punching of counter-protesters and the throwing of tiki-torches by his minions, it had the air of the spectacular, what with uniform chants (“Jews will not replace us!”) and the contrast of the flames against the vast lawn, classical buildings and the dark night sky.

But the next day brought the spectacle of swastikas, Confederate flags, and paunchy men with homemade plywood shields and sticks, mixing things up with scruffy-looking anti-fascist counter-protesters. Even before Fields’ killing of Heather Heyer and maiming of her co-marchers, the sight wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t just violent; it was messy, chaotic violence in bright light of a hot summer’s day.

When Kessler derided the dead young woman as a “fat, disgusting Communist” and suggested she had gotten what what was coming to her, virtually nobody, even among the extremist, racist right, wanted much more to do with him.

Even David Duke, fresh off his self-initiated cameo appearance in the latest Laura Ingraham outrage, apparently declined Kessler’s invitation to speak at this year’s event. And as Right Wing Watch’s Jared Holt reported, neo-Nazi Patrick Little made a point of saying that he’d be in D.C. the day of Kessler’s event, but wasn’t planning to attend.

But as Adam Serwer notes, the far right no longer needs to launch into elaborate cosplay to spread its messages of racism, anti-Semitism and misogyny. The same messages now imbue the rhetoric of less fringy outlets, such as Fox News Channel, where Ingraham recently did a television essay decrying “massive demographic changes” due to immigration that, in her estimation, are rendering America unrecognizable. And they form the framework for the nation’s politics, as more far-right rhetoric is incorporated in the utterances of politicians at the highest levels of government.

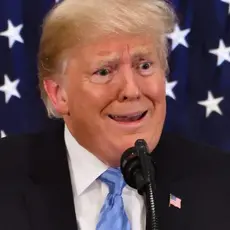

On the eve of Kessler’s march, President Donald J. Trump took to Twitter to condemn “racism of all kinds,” a sort of wink-wink, nod-nod to Kessler, who claims to simply be striking a blow for “white civil rights,” even as he stands surrounded by people with neo-Nazi tattoos and signs bearing racist slogans.

The president, however, did not stay in town as the city mobilized nearly all of its law enforcement resources to maintain order for Kessler’s boys’ club meeting. He was at his golfing resort in New Jersey, just as he was on the day that Heather Heyer was killed.