This piece was originally published on Medium.

The recent revelations about Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s and Attorney General Mark Herring’s history of dressing in blackface serve as an unneeded reminder that despite the Black community’s hard-won social rights, racism still festers as an untreated open wound in our country, with scars so deep they transcend party affiliation and socioeconomic status.

The irony isn’t lost on me that these developments unfolded during Black History Month, the time of year America turns a fraction of its attention to the historic Black figures who have contributed to our society through science, business, the arts, social justice and more.

It’s important to celebrate and pay tribute to these extraordinary Black individuals’ remarkable lives and the lasting impact they have in our community and our country. But given the state of our country and our continued struggles around race, we should also use this opportunity to speak clearly about the racism that continues to take a toll on Black people in America, and to make a clear call to action for progress on racial justice of the broadest sort.

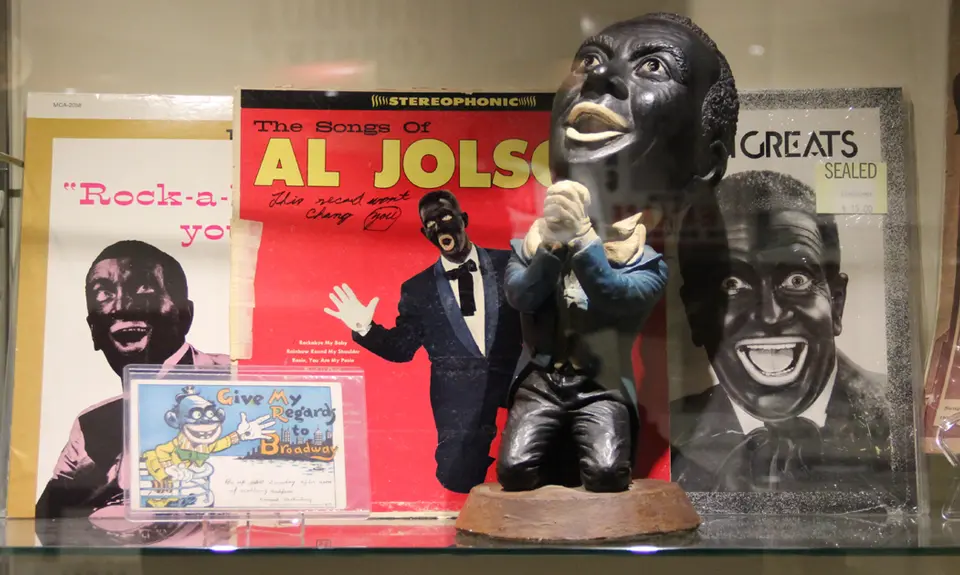

It should go without saying that blackface is not OK. But the news stories on Northam and Herring appearing in blackface in the past make clear that there are far too many people who don’t understand that simple fact. Blackface is just as racist as calling Black people the N-word. Like that slur, it’s not just offensive when it’s used as a weapon to attack a particular individual; it’s a tool to dehumanize and disempower every single Black person, and its malignant impact spreads far beyond the immediate context in which it occurs.

The history of blackface situates how this caricature served to diminish Black people’s humanity and elevate the idea that whiteness is superior, regardless of class or political affiliation. The practice in this country dates back to the emergence of minstrel shows first performed in the 1830s in New York. These shows, which featured white performers with black faces, perpetuated racist stereotypes of Black people as lazy, animalistic, hypersexual, untrustworthy, and subhuman. In fact, the common name for the edifice of racial oppression and discrimination erected during Reconstruction, “Jim Crow” laws, references a minstrel show character played by a white person in blackface. But blackface isn’t relegated to the past — not even the past of the 1980’s, when Northam and Herring participated. In 2018, Megan Kelly defended blackface during her show on NBC; just this week it was reported that Gucci was selling a blackface sweater. The stereotypes that animate minstrel shows and blackface have a lasting impact today: despite our country’s promise of equality, Black people nonetheless find themselves swimming against a constant tide of bias both implicit and explicit.

Anyone who wants to know how dangerous the stereotypes that grow out of blackface can be — and how those stereotypes uphold white supremacy — need only look at the murder of Trayvon Martin as a tragic reminder. We saw firsthand how the portrayal of a young Black man as a dangerous predator played a key factor in his murder, and the gross miscarriage of justice that occurred when his killer was allowed to walk free. As the father of Black sons just about Trayvon’s age when he was killed, the constant awareness that our society will tolerate the cold-blooded murder of young men for no crime other than being Black makes it difficult to accept the idea that blackface can be dismissed as a silly gesture of someone else’s youthful indiscretion.

The destructive, even deadly implications of blackface indicate why we can’t give anyone in public office a free pass to redemption without seeing them do the hard work of recognition and reconciliation for their racism and the white privilege that enables and excuses it. The public does not owe public officials restorative justice while holding hostage seats of power.

If we want to dismantle the structures of racism that undermine the equal dignity of all people and stop America from living up to its promise, we need to hold accountable both our allies and those on the other side of the political divide to a higher ideal of public service.

We can’t fully honor Black History Month unless we seriously commit to challenge the racist structures that our predecessors gave so much to undertake. So as we celebrate the amazing stories of the Black women and men who have helped to change and shape the world, we also need to keep working to make sure that structural racism is dismantled on all fronts.

I am reminded of a favorite Virginia hero of mine, Maggie L. Walker. Mrs. Walker was the first African American female bank president to charter a bank in the United States and the first Black woman to be honored with a statue that sits on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia.

She is also my great, great grandmother.

Mrs. Walker wanted a better state and country, one in which her descendants could live up to their fullest potential without the limitations and threats posed by minstrel shows, naked bigotry and the structures of racism that she had to fight against her entire life.

I want the same thing. And during this Black History Month, I’m calling on all of us to make it happen.