In a move that would essentially block all Central American immigrants fleeing persecution from obtaining legal status through the U.S. asylum program, the Trump administration recently announced that they will deny asylum grants to people who fail to apply for humanitarian protection in at least one other country they pass through on their way to our border. Not only does this blatantly disregard firmly established domestic and international law, it undermines the history of the asylum program generally and the United States’ commitment to defending vulnerable populations against abuse.

The basic concept of asylum is that it carves out a legal status for certain immigrants even if they enter the country illegally or arrive at our border without a valid visa. It is granted to a unique group of people who would be at risk of harm or persecution in their home countries due to factors such as race, religion, or other designated classifications. The law is clear: individuals who are waiting for the adjudication of an asylum claim are not considered undocumented and have legal rights to work and live here. Unfortunately, these cases can take anywhere from one to 10 years to make their way through our immigration system.

Asylum law and the rules for determining the validity of these claims were established through a combination of international treaties and domestic law. The program has proven not only an effective tool for protecting vulnerable populations escaping persecution, but has served as a crucial pillar in immigration law and transformed the United States’ understanding of its responsibilities in combating human rights abuses and providing humanitarian relief.

Of course, since the 2016 election, asylum seekers and refugees have been an ongoing target for Trump, who has made his campaign’s "war against immigrants" a central component of his presidency. He has long capitalized on the bigotry of his base by spewing anti-immigrant rhetoric and proposing radical—often irrational and unconstitutional—changes to our immigration system. This latest policy change is one more radical piece of an already extreme agenda that undermines the nature of our historical approach to granting humanitarian relief.

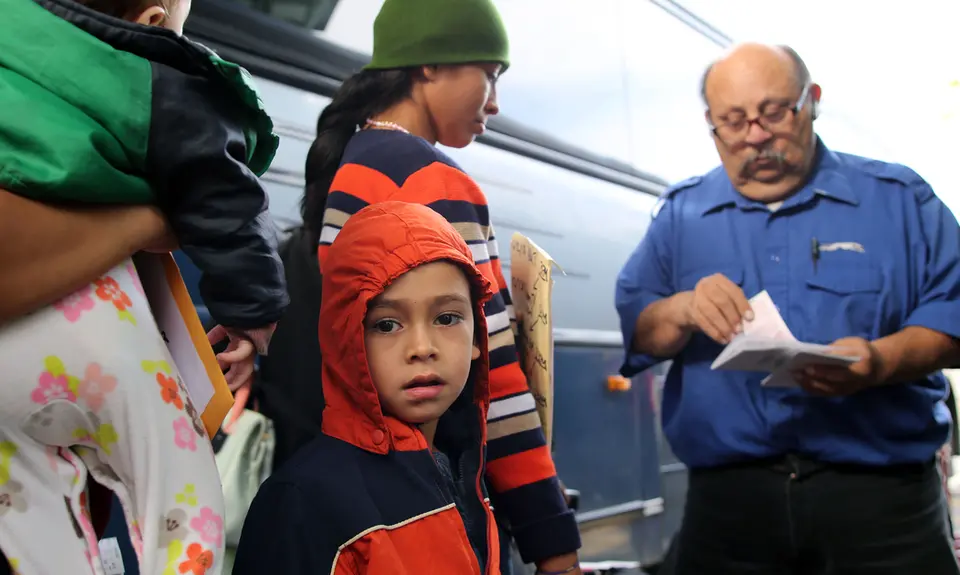

Under the new rule, Hondurans and Salvadorans must apply for asylum in Guatemala or Mexico and prove they were denied status there before becoming eligible to apply for U.S. asylum. The rule carves out a narrow exception for those who have been a “victim of a severe form of trafficking in persons,” but provides little guidance for what that entails. This would undercut decades of immigration law and policy and deeply discount the historical context of why this status was established in the first place. A group of immigration organizations and legal institutions, including the ACLU, have already challenged Trump in court, arguing that this new policy is contrary to both international and domestic law.

The administration’s rule would be a blatant violation of a number of treaties the U.S. signed decades ago in response to our past failures to adequately protects vulnerable populations. To understand these treaties and how they helped develop modern asylum law, we must also understand the historical context that led to the United States recognizing the need to carve out special protections for those fleeing violence and persecution.

After the atrocities committed during the Holocaust, many countries began examining their own role in the genocide and their failure to welcome and protect Jewish refugees who risked their lives to escape only to be met with closed doors. The United Nations began constructing a formal definition of a “refugee” in the 1950s, with the intention of organizing a universal agreement among its members where all participating states would commit to protecting individuals fleeing persecution. This definition was expanded in 1967 by the UN in its Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees and formally adopted by the United States in 1968.

Protecting oppressed people fleeing persecution is part of who we are. And until recently, the United States has taken its commitment to the international community to uphold these principles very seriously.

Trump’s new proposal would directly contradict a number of our obligations and set a poor example to every nation who has committed to providing a special immigration status to those who qualify. For our country to uphold the values it claims to represent and its commitment to combat human rights abuses, adhering to these agreements is absolutely essential and a requirement under international law.

Moreover, many legal experts have argued that the new rule is also in direct conflict with our own immigration code, which was adopted by Congress through the Refugee Act of 1980 and codified the same refugee definition set forth by the United Nations. Specifically, the new policy is inconsistent with the “safe third country” rule, a well-established exception in asylum law that has a very specific set of provisions surrounding its implementation. The exception states that the United States can deny protection to an asylum seeker only if: “(1) a bilateral or multilateral agreement exists between the U.S. and a foreign country; (2) the immigrant’s safety and freedom would not be threatened if he remains in the third country; and (3) the immigrant would have “access to a full and fair procedure for determining a claim.”

Right now, the only country the United States has a “bilateral or multilateral” agreement with is Canada, and all attempts so far to create similar agreements with Mexico or Guatemala under Trump have failed. There is also ample evidence—reports from the U.S. State Department—suggesting that Central American migrants in both Mexico and Guatemala have been targeted for violent crimes such as kidnapping and extortion, indicating that the second condition of the “safe third country” rule would not be met as neither country can guarantee the safety and freedom of asylum seekers.

Finally, nearly all immigration experts agree that neither Mexico nor Guatemala has the infrastructure or legal system in place to support the influx of asylum seekers fleeing violence in Central America. For example, Guatemala has just three officers in their entire country who are currently trained to interview asylum seekers and determine the validity of a claim. Even if the United States were to somehow reach a “bilateral or multilateral” agreement with Guatemala and Mexico, and if those countries invested the millions of dollars it would take to build a system of immigration processing from scratch, it would take decades of training before an appropriate number of officers and judges could reach the level of expertise needed to provide a “full and fair procedure,” which the United States considers a remarkably high legal standard to obtain.

Ultimately, the glaring inadequacies of Trump’s plan and his blatant disregard for laws and policies that our country has established over decades indicate that the challenge to this new rule in court is likely to be successful. However, the aggressive nature of Trump’s agenda is especially troublesome given his administration’s pattern of sidestepping court orders and ignoring our system of checks and balances completely. Unfortunately, immigrants continue to suffer greatly under his administration