“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

In July 2020, eight Trump judges on the Ninth Circuit tried to dismiss without a trial a class action lawsuit by Southern California Muslims alleging that the U.S. government had illegally spied on them because of their religion. The full Ninth Circuit declined to do so in the July 2020 case of Fazaga v. FBI.

In 2006-2007, an FBI informant allegedly infiltrated the Muslim community in Southern California and gathered detailed information about hundreds of people’s backgrounds, religious beliefs, political views, and other private matters in what was called “Operation Flex.” This included hundreds of hours of video recordings of the interiors of mosques, homes, businesses, and associations, as well as thousands of hours of audio recordings of conversations, public discussion groups, classes, and lectures. Several of the targets filed a class action lawsuit alleging unconstitutional searches (“surveillance claims”) and anti-Muslim discrimination (“religion claims”).

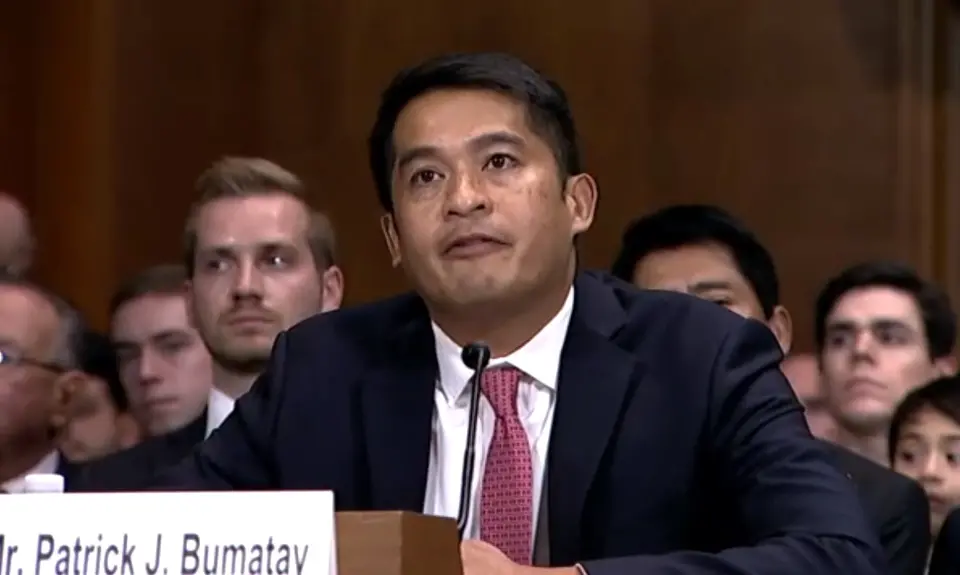

The district court judge dismissed almost all of the claims without a trial, based on something called the state secrets privilege, which was established by the Supreme Court in a 1953 case called Reynolds v. United States. The judge did so on the basis of the government’s claim that moving forward could reveal classified information and threaten national security. In 2019, however, a unanimous three-judge Ninth Circuit panel reversed the lower court, ruling that the claims could proceed, but with special processes set forth in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) to protect national security. In 2020, the circuit as a whole chose to let that ruling stand, over the dissent of eight Trump judges— Patrick Bumatay, Bridget Bade, Mark Bennett, Daniel Bress, Daniel Collins, Kenneth Lee, Ryan Nelson, and Lawrence VanDyke—and two George W. Bush judges.

Judge Bumatay, writing for the dissenters, accused the panel of violating the Constitution’s separation of powers by second-guessing the executive branch’s ability to protect classified information. But in her concurrence to the circuit decision against en banc reconsideration, Judge Marsha Berzon explained that the state secrets privilege is not “a magic wand that the Executive may wave to remove certain information from litigation or, if necessary, end the case.” She quoted the Supreme Court’s statement in Reynolds that it is up to the courts to determine if the executive’s claim of privilege is appropriate.

Bumatay argued that Reynolds requires dismissal in this case. But Berzon explained that after that case was decided, Congress passed FISA and thereby replaced the common law remedy of dismissal in cases involving electronic surveillance. FISA established a “truncated and secrecy-protective manner” for courts to consider classified materials. Under that law, the judge examines the classified evidence outside the presence of the public or the plaintiffs, then determines whether the government violated the law as claimed by the plaintiffs. When judges makes this determination, they “may” disclose classified material to the plaintiffs “only where such disclosure is necessary to make an accurate determination of the legality of the surveillance.” In that way, the courts still protect national security interests and the executive branch’s prerogatives in that area.

Had the Trump judges had a majority, targets of a significant and potentially unlawful surveillance of a large Muslim community would have no way to vindicate their rights.