“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

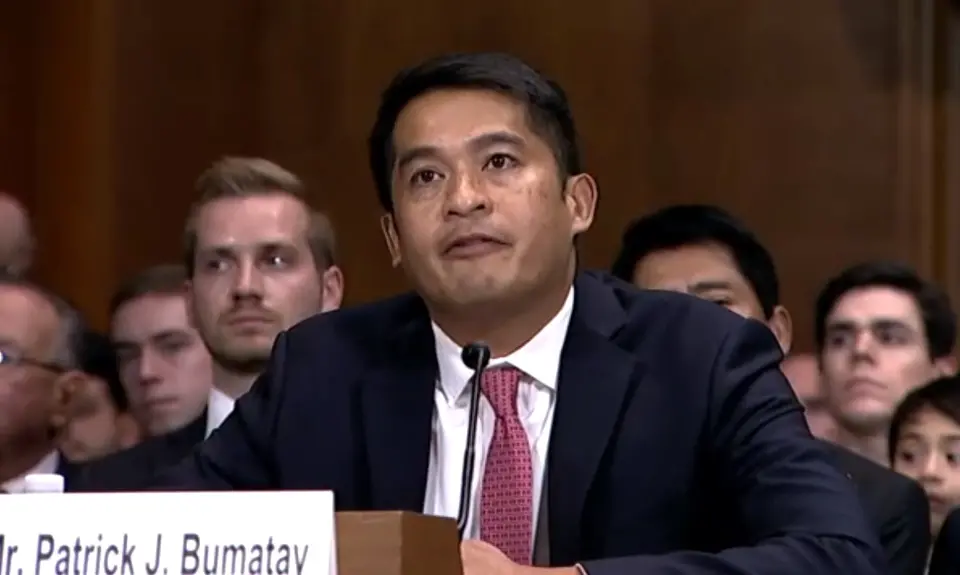

Nine Trump Ninth Circuit judges, including Patrick Bumatay, Mark Bennett, Ryan Nelson, Bridget Bade, Daniel Collins, Kenneth Lee, Daniel Bress, Danielle Hunsaker, and Lawrence VanDyke , argued in dissent that the full court should reverse a panel decision and rule that a federal border agent cannot be held liable for using excessive force and retaliating against a US citizen by getting the IRS to audit him. The full Ninth Circuit majority rejected that view and the victim will get a chance to prove his claims as a result of the panel decision in Boule v Egbert.

Robert Boule owns, operates, and lives in a small bed-and-breakfast in Washington adjacent to the US-Canadian border. Boule is a US citizen and has a record of cooperating with the US Border Patrol, including in inquiries about his guests. One day in 2014, he answered routine questions from Border Patrol agent Erik Egbert about a guest arriving that day from New York who had previously been in Turkey, and Egbert said nothing. When the car carrying the guest arrived, however, Egbert pulled into the inn’s driveway behind the car. Egbert got out and approached the vehicle carrying the guest, with no explanation. Boule twice asked Egbert to leave, the second time while standing in between Egbert and the car carrying the guest. Egbert refused to leave, gave no explanation, and “shoved Boule against the car,” and then “grabbed him and pushed him aside and onto the ground.” Boule later sought medical treatment for back injuries.

Egbert opened the car door and asked the guest about his immigration status. Boule made a phone call to summon a supervisor, who determined after arriving at the scene that the guest was “lawfully in the country,” and the agents then left. When Boule then complained about Egbert, the agent “retaliated against Boule” by asking the IRS to conduct an audit of him, which took several years and cost Boule $5000 in accountant fees. Egbert also got the Social Security Administration and several state and local agencies to conduct “formal inquiries into Boule’s business activities” which, like the IRS audit, did not result in any charges against him.

Based on these facts as alleged in his complaint, Boule filed a lawsuit against Egbert in federal district court for the use of excessive force under the Fourth Amendment and for retaliation in violation of the First Amendment. Because Egbert is a federal and not a state law enforcement official, Boule relied on the Supreme Court’s long-established Bivens doctrine, which authorizes people to hold federal law enforcement agents accountable for constitutional violations that injure them under some circumstances. Because the Supreme Court has not stated specifically that Bivens applies to actions by Border Patrol agents and conduct that violates the First Amendment, however, the lower court granted summary judgment to Egbert and dismissed the case without a trial.

A three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit reversed and ruled that Boule should have the chance to prove his claims. The panel acknowledged that the Court had not stated as yet that Bivens applies in those contexts, and that the Court has carefully instructed that before a federal court makes such an extension, it must “consider the risk of interfering with the authority of the other branches” of the federal government and “ask whether there are sound reasons to think Congress might doubt the efficacy or necessity of a damages remedy,” and “whether the Judiciary is well suited,” without Congressional action, to “consider and weigh the costs and benefits of allowing a damages action to proceed” under the Constitution. Based on those criteria, the panel determined that there were no adequate and “available alternative remedies,” and that Boule should be able to proceed with his claims under both the Fourth and First Amendments.

With respect to the Fourth Amendment excessive force claim, the panel explained that Boule was bringing a “conventional” charge of excessive force like those “routinely brought” under Bivens against federal law enforcement officials like FBI agents. Although the Court had twice declined to permit such lawsuits against Border Patrol agents, the panel went on, those cases were brought by “foreign nationals” and involved unique issues of “national security.” In contrast, the panel stated, Boule’s case was brought by a US citizen concerning excessive force by a “rank-and-file” border patrol agent against him “on Boule’s own property” and did not involve any national security or foreign policy concerns. The panel noted that numerous courts around the country, including the Ninth Circuit, had allowed such lawsuits “against border patrol agents under the Fourth Amendment,” and that Boule’s claim is “part and parcel” of the “common” types of claims unfortunately brought against law enforcement officials and should be allowed to proceed.

Although the Supreme Court had never specifically allowed a First Amendment damages claim against a federal official, the panel stated, it had “explicitly stated” in one case that “such a claim may be brought.” The Supreme Court has recognized, the panel continued, that it has “long been the law” that federal officials “violate the First Amendment when they retaliate for protected speech.” The Ninth Circuit had previously “upheld a Bivens claim” under the First Amendment, the panel went on, and a Supreme Court case that had failed to do so was clearly distinguishable because it involved a federal employee complaining about a supervisor, not a “vengeful officer” who the Court recognized could be sued under the First Amendment for retaliation. In short, there were no “special factors” suggesting the court should not allow Boule’s First Amendment retaliation claim.

Trump judges Bumatay and Bress wrote harsh dissents, joined by Trump judges Bade, Collins, Bennett, Hunsaker, Lee, Nelson, and VanDyke plus a few others. They would have “corrected” what Bumatay called the panel’s “error” through review by the full court. Bumatay called the Bivens doctrine a “judicial usurpation” of what he deemed the “legislative function” to create remedies for constitutional violations, about which he claimed the Court has since had “buyer’s remorse” and, in his view, has made any expansion of the doctrine whatsoever a “dead letter.” He asserted that the panel had “disregarded” Supreme Court precedents and improperly become a “quasi-legislature.” Bress similarly concluded that the panel decision was “inconsistent” with Supreme Court precedent.

Although the Trump judge dissenters may well be correct that the current Supreme Court would disagree with the panel ruling, that decision clearly explained that authorizing Boule to sue Border Patrol agent Egbert for excessive force and retaliation under the Constitution was consistent with Supreme Court precedent and the proper role of the courts, as discussed above. The case is yet another example of Trump judges voting against accountability for misconduct by law enforcement officials. Fortunately, because the Trump judges did not have enough votes, Boule will have the opportunity to seek such accountability. With several judges on the Ninth Circuit planning to take senior status, which means they would no longer be eligible to participate in full court votes like this one in the future, it is crucial to our fight for our courts that Biden nominees to fill these seats be confirmed as soon as possible,