“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties.

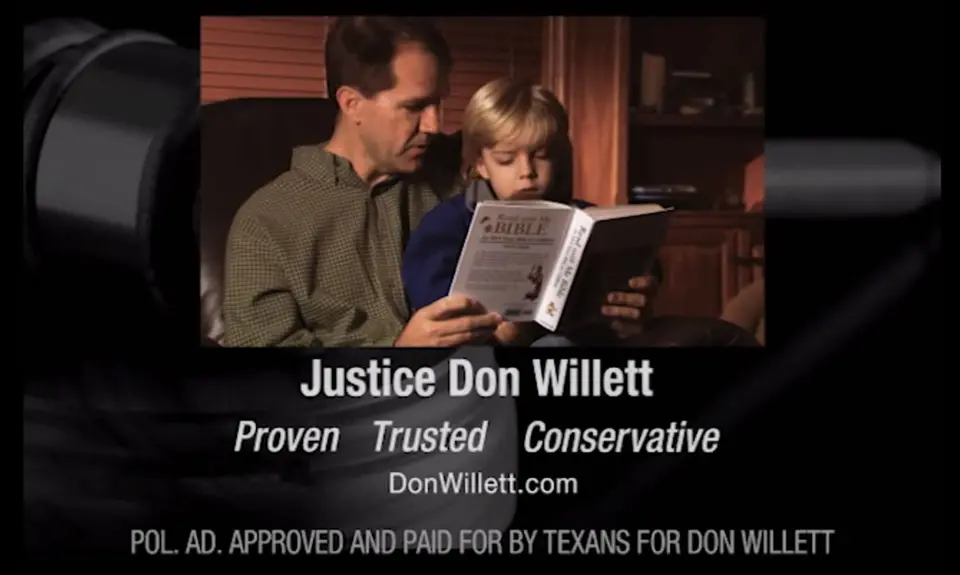

In Thomas v. Bryant on September 3, Fifth Circuit Trump judge Don Willett tried in dissent to reverse a district court finding that the state district lines for Mississippi’s 22nd District were drawn in a way that illegally diluted the votes of African American residents under the Voting Rights Act (VRA). He also suggested that a race-conscious remedy for a proven VRA violation violates the Constitution, directly contrary to Supreme Court precedent. A majority of the judges on the very conservative full 5th Circuit, which includes five Trump appointees, has already decided on its own motion to rehear the case.

In 2012, Mississippi redrew the boundaries of Senate District 22 to “stretch over 100 miles,” including the predominantly African American and impoverished Mississippi delta area plus several wealthy, predominantly white areas. Although the district was “barely” majority-minority at 50.6 percent, it had never elected an African American state senator, and an African American candidate lost in 2015, the first election when the new district lines were used.

In 2018, several District 22 African American voters sued state officials under section 2 of the VRA, which bars state and local voting actions with discriminatory effect. The case was filed pursuant to the Supreme Court’s Gingles decision, which ruled that it is illegal under VRA for a state to draw district lines in a way that “dilutes” the voting strength of minorities and deprives them of a real opportunity to “elect candidates of their choice.”

The district court proceeded to conduct a two-day evidentiary hearing and concluded in early 2019 that District 22 violated VRA based on the “totality of circumstances” under Gingles. This was based on specific findings of key factors under Gingles that demonstrate a VRA violation, including a history of voting-related discrimination, the fact that voting in the area tends to be “racially polarized” including “white bloc” voting, the extent to which minorities suffer from “the effects of past discrimination” in areas like employment and education that “hinder their ability” to vote, and the fact that no candidate preferred by African American voters had ever been elected senator in District 22. The court went on to order a remedial redistricting plan when the state failed to do so, but then withdrew its remedial order when the state enacted a redistricting plan that made the district more compact and increased the percentage of African American voters.

Mississippi nevertheless appealed, and a 5th Circuit panel affirmed in a 2-1 majority opinion by Reagan appointee W. Eugene Davis. The majority explained that factual findings by a lower court must be accepted unless “clearly erroneous,” carefully reviewed the district court’s judgment, dismissed as moot the appeal of the lower court’s remedial order since it was no longer in effect, and affirmed the decision that as originally drawn by the state, District 22 violated the VRA because it operated to “dilute African-American voting strength” and “deprive African-American voters of an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.”

Willett harshly dissented. Initially, he raised procedural objections to the district court ruling, asserting that the voters had waited too long to bring their challenge since there were some objections to the redistricting plan as early as 2012, and that the decision caused too much disruption because it came too close to a scheduled election. He also suggested it “warrants closer study” as to whether the case should have been heard by a three-judge district court, which is what happens under federal law when redistricting is challenged as unconstitutional.

Judge Davis explained carefully what was wrong with these arguments. It wasn’t until the new district lines were actually used in 2015 that their harmful impact became clear, Judge Davis noted, and the lawsuit was filed within the usual three-year statute of limitations period after that. The changes ultimately made by the state’s redrawn map in 2019 affected only 2 senate districts and eight precincts, were adopted more than seven months before the election, and were not “unduly late or disruptive,” Davis went on. In contrast, the majority pointed out, in a key Supreme Court case relied on by Willett to argue about the timing of election remedies, the Court had approved a district court order that “revised a state’s entire legislative map four months closer” to an election than the ”two-district change imposed here.” With respect to the three-judge court issue, the majority noted that under the “clear” statutory language, courts across the country have for “decades” handled Section 2 challenges as matters to be decided by a single judge without a “hint of jurisdictional doubt” to this “settled law” by any higher court, and that there was “no caselaw” to the contrary.

Most of Willett’s attack was focused on the merits of the lower court’s decision. Although praising the VRA in general, Willett claimed that the majority and the lower court were improperly using it to effectively require a “guarantee” of electoral success for African Americans. He asserted that the district court did not have sufficient facts to warrant its ruling and that a VRA violation should not be found since the district as drawn in 2012 was majority minority. And he criticized the remedy initially ordered by the lower court, strongly suggesting that an “overt race-conscious remedy” violates (or appears to “run headlong into”) the Fourteenth Amendment.

The majority rejected Willett’s claims. The district court was clearly not requiring a “guarantee” of electoral success for minority voters, Davis explained, but simply using the previous lack of electoral success as a factor, precisely as the Supreme Court had ruled. “Unimpeachable authority” in the 5th Circuit and elsewhere, including the Supreme Court, has “rejected” the notion that vote dilution cannot occur where a racial minority is a “bare” majority of voters, Davis also noted. The majority specifically criticized Willett for his failure to analyze the district court’s “extensive factual findings and legal analysis”, and for turning “a blind eye” to the evidence showing “stark” socioeconomic factors lowering African-American turnout in accord with Gingles. And Davis explained that the Supreme Court has specifically rejected Willett’s claim about race-conscious VRA remedies just last year, when it stated that “compliance with the VRA’” may warrant “the consideration of race in a way that would not otherwise be allowed.”

Unfortunately, Willett may have the last word in this case because the full 5th Circuit, including all five Trump judges, agreed on September 23 to rehear it. Whether in this or in future cases, the adoption of Willett’s views threatens to seriously weaken the VRA and to allow states to adopt redistricting plans that will significantly harm minority voters, particularly in the deep south states that make up the 5th Circuit.