“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties.

Trump Fourth Circuit judge Julius Richardson dissented from an October decision in Chavez v. Hott and argued that the government should be able to indefinitely detain refugees, who are seeking to avoid being returned again to their home countries because of a reasonable fear of torture or persecution, without even a bond hearing. Even though an asylum officer found that the individuals in this case had such a reasonable fear, the proceedings can take months or more to complete, and the government imprisoned or detained them all until each completed the proceeding. Both the district court and the Fourth Circuit majority agreed that all individuals in the class represented by the plaintiffs are entitled to an individualized bond hearing that could lead to their release during the proceeding.

Under federal law, individuals who have been removed or deported from the United States, but subsequently return here due to fear of torture or persecution in the home countries to which they were sent, can apply for “withholding of removal.” Under that procedure, they would not be granted asylum, but they could not be sent back to their home countries, and instead would either be allowed to stay in the U.S. or be removed to a different country.

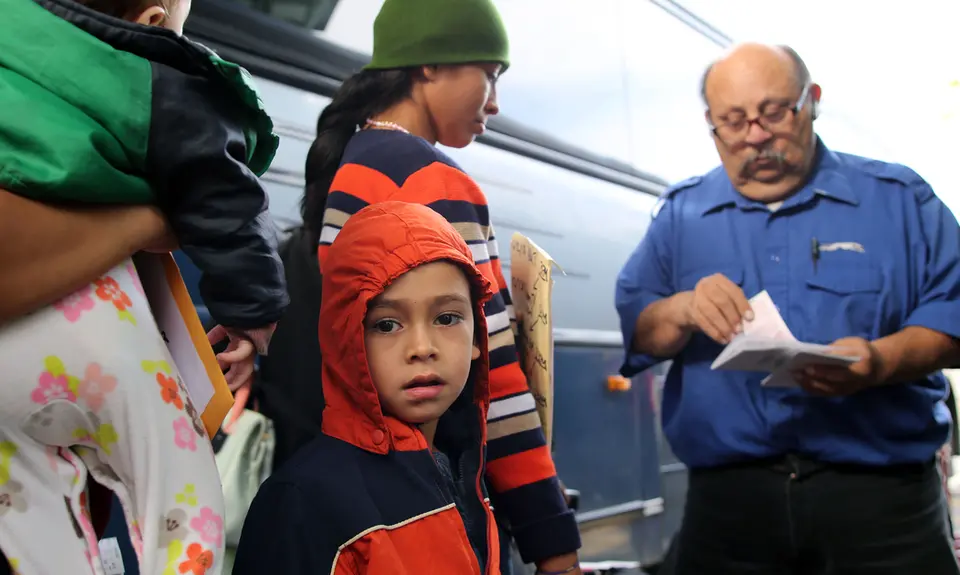

In this case, nine individuals were deported from the U.S. to their home countries in South and Central America, where they claimed they faced actual or threatened “persecution or torture,” including “death threats.” “Fearing for their safety,” they returned to the U.S. without authorization, and the orders of removal were reinstated against them. A government asylum officer interviewed them, and found that “in every case,” they had a “reasonable fear” of “persecution and torture,” so they were placed into proceedings before immigration judges to apply for “withholding of removal.”

But the government decided to keep the refugees detained while the proceedings were pending, and refused to grant any of them a hearing so that they could apply for temporary release, even to help “make their case before an immigration judge” for withholding of removal. The individuals then filed lawsuits in Virginia seeking such bond hearings, and several sought to represent the class of all individuals being detained in Virginia while they sought withholding of removal.

The district court granted summary judgment in favor of the detained individuals and the class, ruling that they were entitled under federal law to hearings to seek their temporary release while the withholding of removal proceedings were pending. Specifically, the judge ruled that the plaintiffs were being held pursuant to a federal statute that explicitly allows “discretionary release on bond” of individuals being detained “pending a decision” on whether they would be “removed from the United States.” The government appealed, and a 2-1 majority of a panel of the Fourth Circuit affirmed the decision.

Judge Richardson dissented, agreeing with the government’s claim, in accord with the views of two other appellate courts, that the individuals were being imprisoned pursuant to a different federal law, which requires that a person who has been “ordered removed” must be detained without bond during a period not to exceed 90 days, after which the person “shall” be removed.

As both the district court and the Fourth Circuit majority explained, however, it was the first and not the second law that applies in this case, because until the “withholding of removal” procedure is complete, there has not yet been a decision on “whether petitioners will actually be removed” from the U.S. That procedure, the district court explained, “takes substantially longer than 90 days,” further showing that the statute relied on by the government does not apply. The majority accordingly agreed with the district court, and a decision by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, that individuals applying for “withholding of removal” can seek to be released from custody while those proceedings are pending.

As the majority emphasized, its decision does not mean that these or other refugees seeking withholding of removal will actually be released while the proceedings are pending. But it does mean that they will be allowed to “make their case for release on bond to immigration judges in individualized hearings” while the withholding of removal proceedings are pending. If Richardson’s view had prevailed, they would not even get that chance, and would be required to remain in prison for months while the proceedings continue.