“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

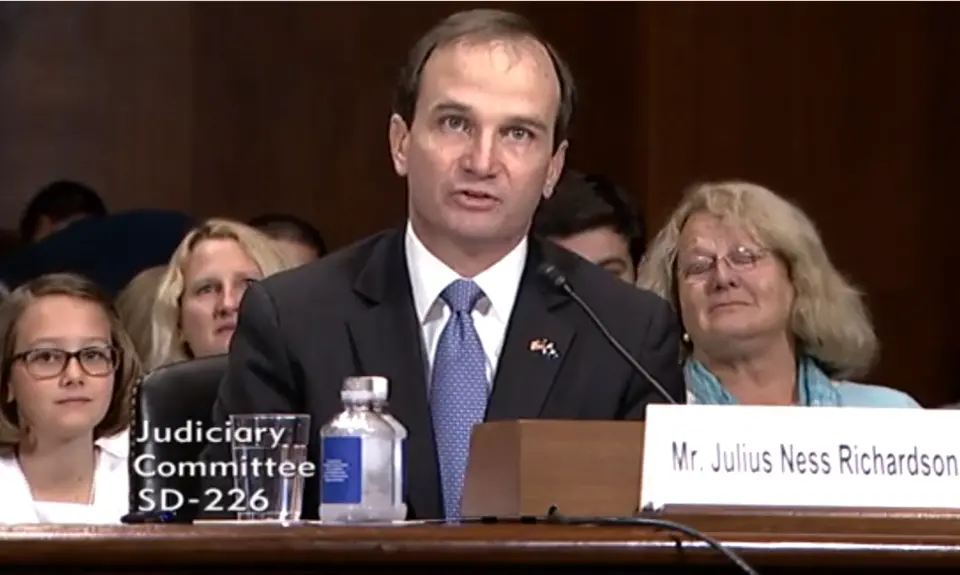

Trump Fourth Circuit judge Julius Richardson wrote a 2-1 decision to affirm summary judgment in a case in which the state suppressed evidence that tended to prove a man’s innocence and, in doing so, violated his due process rights. The January 2020 case is Long v. Hooks.

In 1976, an African American man entered the house of North Carolina woman Sarah Bost in an attempted robbery. The man demanded that Bost, a white woman, give him money; when she didn’t produce any, he threw her to the ground and raped her. During the assault, Bost’s phone rang, startling the attacker and prompting him to quickly flee the scene. Bost told her neighbor that she was raped by a Black man and later visually identified Ronnie Long as her rapist, and he was subsequently arrested, charged, and convicted of burglary and rape.

Since then, Long has consistently maintained his innocence. After he spent almost 30 years in prison, a state court finally compelled state government officials to turn over all evidence related to Long’s case, including a detective’s forensic report. The report revealed that extensive testing of various items from the crime scene did not match Long’s samples. Specifically, the report found that Long’s hair did not match the hair found at the crime scene, and was not found on Bost’s clothes. Additionally, no paint or carpet fibers from the crime scene were found on Long’s clothes, and burnt matches at the crime scene did not match the matches taken from Long’s car. In addition, the police had recovered a sample of the assailant’s semen, but it was never tested. None of this information was disclosed to Long before trial. Instead, he was given a different report that conspicuously omitted the tested items that suggested his possible innocence.

After Long received the new evidence, he filed a post-conviction motion in state court, contending that the government had violated the longstanding Supreme Court principle established in Brady v. Maryland that the prosecution must turn over any evidence that suggests the defendant’s innocence. The state court rejected Long’s motion, claiming erroneously that Brady required him to prove “by a preponderance of evidence” that the withheld evidence “would have changed the result” if it had been provided before trial.

Long’s case then went to federal court, where a district court also rejected Long’s claims. On appeal, all three judges on the Fifth Circuit panel agreed that the state court had incorrectly interpreted Brady. But Richardson’s opinion claimed that it did not matter, because the state court also stated that the value of the withheld evidence was “so minimal that it would have had no impact on the outcome of the trial.”

Judge Stephanie Thacker strongly dissented in an extensive 25-page opinion. She explained that the state court’s “no impact” comment was “inextricably intertwined” with its error in interpreting Brady. She went on to demonstrate that the “no impact” conclusion was “objectively unreasonable” based on a detailed analysis of the withheld evidence and the limited evidence presented against Long. She noted, for example, that contrary to the majority’s claim, Bost’s initial description of her assailant “did not” match Long, and that the record showed that a detective who was a key prosecution witness at trial “lied [r]epeatedly.” She also noted that Long had an actual alibi that the state did not specifically refute.

Judge Thacker pointed out that for “more than 43 years,” Long had maintained his innocence and “continued to search for the truth.” But Richardson’s decision, she concluded, provides “incentive” for the government “to lie, obfuscate, and withhold evidence for a long enough period of time that it can then simply rely on the need for finality.” Richardson’s dangerous decision to minimize evidence that could exonerate Ronnie Long doesn’t just rob Long of the fair trial he deserves – it upholds a centuries-long pattern of the presumption of guilt when white women accuse African American men of sexual violence. All Americans deserve the same protection under the law; unfortunately, Long will not have the chance to argue his innocence.

Note: The initial draft of this post was composed by PFAW legal intern Oliver Telsuma.