The beloved poem “Dream Deferred” written by Langston Hughes embodies the heart and spirit, the drama and tension, the past and present narrative regarding the issue of reparations, making amends for a wrong done, for generations “post-” enslavement.

Reparations, for many African Americans, is woven into the fabric of the January 1, 1863, order issued by President Abraham Lincoln. Known as the Emancipation Proclamation, or Proclamation 95. It took affect “only in Southern states that were in rebellion.” But this proclamation essentially “led the way to total abolition of slavery in the United States.” It instilled a sense of hope for immigrants bought by force to this county, that the dream of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” would be actualized.

Reparations, “paying money to or otherwise helping those who have been wronged,” is what many believed then and now to be the Special Field Order (No. 15), issued in January of 1865 by General William T. Sherman, becoming known as “40 acres and a mule” for those who suffered under a form of state sanctioned domestic terrorism.

June 19 is not the day that enslaved people of African descent were actually “freed”; rather, it is the day that many were finally told they were “free’ and thus June 19 is commemorated as the “last day” of enslavement in the United States. Major General Granger did not specifically address the issue of reparations, “the action of repairing something,” on June 19, 1865, when he issued the order that “the people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.” Historian Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., notes that Granger “had no idea he was establishing the basis for a holiday,” which would later become a milestone anniversary which has provided a forum to raise the issue of reparations!

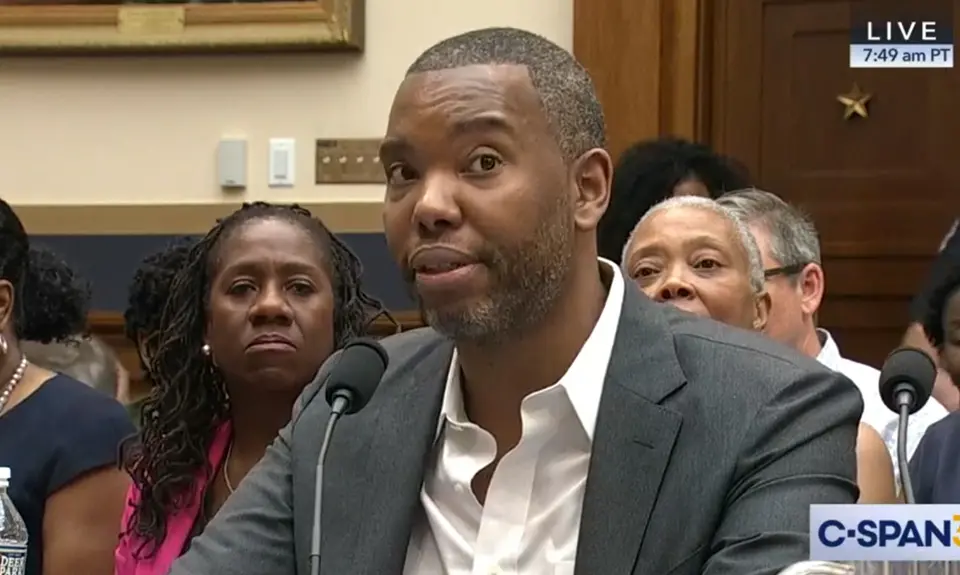

Last month, on June 19, 2019, a day that has been deemed historic, Congress held the first hearing on a bill on reparations, originally introduced in the ‘70s by the Honorable John Conyers, “The Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African American Act,” or H.R. 40. If passed, preferably with bipartisan support, the Act would “address the fundamental injustice, cruelty, brutality, and inhumanity of slavery in the United States and the 13 colonies, between 1619 and 1865 … and consider a national apology and the impact of the institution of slavery and economic discrimination on living African-Americans, to make recommendations … on appropriate remedies.”

Disparities rooted in white supremacy — including slavery, segregation, and racial and economic inequities — have survived since the Middle Passage. Discrimination and racism throughout history are clear in the Jim Crow laws of the Reconstruction era and the subsequent racial segregation in education, housing, employment, and other institutions. It is evident in voter suppression, mass incarceration, the disproportionate impact on African American people in the forms of police brutality, educational disparities, maternal mortality, the racial wealth gap and in a host of prejudice, intolerant, bigoted policies and social practices. Indeed, white supremacy is deeply embedded into American policies, systems and culture.

A primary argument against reparations — and one used by Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky recently — is that those who are “currently living” are not “responsible … for something that happened 150 years ago.” McConnell, and others who think like this, are wrong because the effects linger and white America continues to benefit. Additionally, as a matter of fairness, just as it was fair for Germany to attempt to compensate Holocaust survivors for the atrocities against them during World War II and the U.S. governments “redress” for the inhumanity of internment camps of Japanese Americans, it is fair and very reasonable to ask that the impact of these injustices, however long ago the initial occurrence, be offset.

Although a substantive reparations program could never erase the stain, sting, stigma or shame that emerged from what was the “campaign of terror” that immediately followed the Civil War — or the continuation of institutionalized racism, discrimination, and the attacks on human and civil rights that continue to linger today — it would be the right step toward a long overdue apology and the ownership of responsibility by this government for the wrongs of yesterday and their continuing effects through the present. This step would give clarity and a profound response to why the American federal government should provide reparations to the descendants of women and men enslaved in this country.

On June 4, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson gave a commencement address at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he said that “… nothing in any country touches us more profoundly, and nothing is more freighted with meaning for our own destiny than the revolution of the Negro American. In far too many ways they have been another nation: deprived of freedom, crippled by hatred, the doors of opportunity closed to hope … much more difficult to explain, more deeply grounded, more desperate in its forces is the devastating heritage of long years of slavery; and a century of oppression, hatred, and injustice … But freedom is not enough…” and frankly, neither is another hearing.

For those new to the conversation and those who have dedicated their lives to reparations, three things were gleaned from the thought-provoking presentation on H.R. 40: (1) the varying voices represented demonstrated both the diversity within the African American community on this issue as well the complexity of righting this wrong; (2) the barriers African Americans confront in terms of access to resources, power and equitable opportunity that continue to limit our families and community today and into the future; and, (3) while African Americans have been able to achieve a version of the American Dream, for the few who did, “there are so many thousands” who have not.

We are grateful to those who organized and participated in the hearing and the role it played in updating and advancing the vision. Yes, pass H.R. 40, convene the Commission, study our people once again and keep it moving!

Reparations says that those who died for dignity and release from bondage did not do so in vain.

Reparations says that hope still lives for us and our neighbors — hope for stronger public school system, affordable and safe housing, a livable wage, reproductive justice, economic security, Shelby v. Holder, immigration, addressing disproportionate representation in critical health conditions, African American farmers, criminal and juvenile justice reform, LGBTQ+ civil rights, and religious liberty for the oppressed, underserved, disenfranchised, disrespected.

The 2019 hearing on reparations was not the first and certainly, hopefully won’t be the last. However, in this case, the means do justify the end as another way to remember that the dream for equity and justice is still deferred — and more importantly, still worth fighting for.