“Confirmed Judges, Confirmed Fears” is a blog series documenting the harmful impact of President Trump’s judges on Americans’ rights and liberties. Cases in the series can be found by issue and by judge at this link.

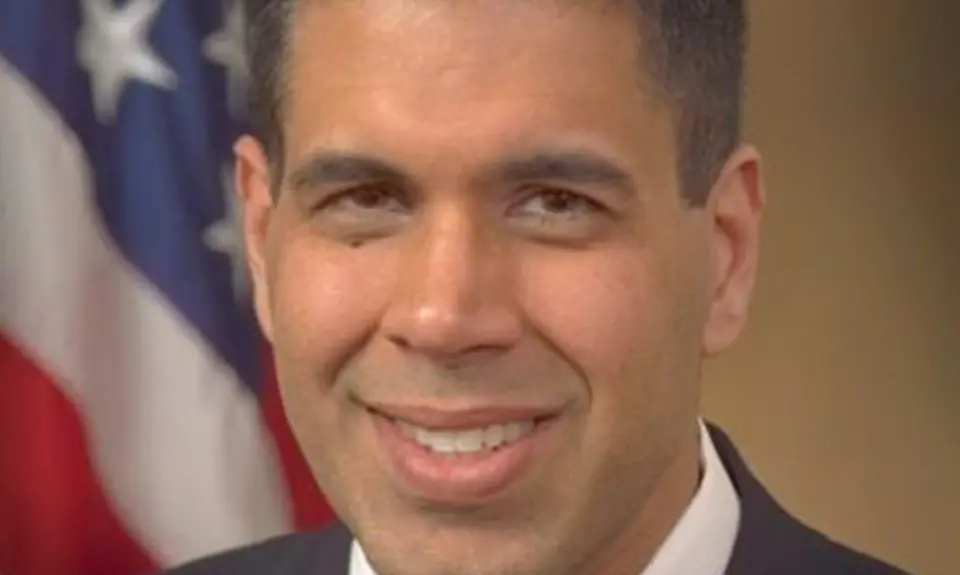

Trump Sixth Circuit judge Amul Thapar cast the deciding vote in a 2-1 panel decision that required a family to return to Senegal even though they’d shown they would be targeted for female genital mutilation (FGM). The January 2020 case is Dieng v. Barr.

Aminata Dieng and her husband Ousseynou Ndiaye Lo, both from Senegal, have been in the U.S. since 2003 and 1997, respectively. In 2018, they sought to have their previously unsuccessful asylum case reopened, based on new information about changed circumstances in Senegal. The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) denied their petition in a decision upheld by the 2-1 majority of the Sixth Circuit. Judge Thapar joined Judge Alice Batchelder’s majority decision.

Dieng had fled Senegal because her family had tried on multiple occasions to inflict FGM on her, threatening to kill her if she did not submit. During her original asylum proceeding, she said she thought she was too old to be subject to FGM, but she was afraid for her two daughters, both of whom were born after she had fled her home country, one in the United States and thereby a U.S. citizen. But the BIA denied Dieng’s original asylum petition in 2010, concluding that she hadn’t demonstrated a well-founded fear of future persecution, and could instead move to a part of Senegal where FGM is practiced “less frequently,” with no reason to think her relatives (if still alive) would know of her whereabouts.

In 2018, Trump’s Department of Homeland Security took steps to enforce the BIA’s earlier ruling and force Dieng and Lo back to Senegal. They sought to reopen their case, claiming that circumstances in Senegal had worsened since 2010. Dieng testified that her Senegal relatives were not just still alive, but had learned she might return and renewed their threats against her and, this time, her daughters. She also submitted corroborating letters from her cousin in Senegal who was being “harassed” by Dieng’s aunts and uncles for information about her planned return. Lo also submitted similar letters from his family in Senegal, which indicated it would not be safe to stay with them. In addition, Dieng’s cousin warned that she had been forced into FGM as an adult, suggesting that Dieng’s earlier assumption that she was too old to be targeted was incorrect.

Judge Helene White pointed out in her dissent that Dieng and Lo’s letters and the other documentation they submitted constituted “new evidence” that it was unsafe to return, evidence that the BIA should have considered. But Judge Thapar upheld the BIA’s refusal to credit this evidence on the basis that it was “self-serving and speculative.”

The majority was similarly unwilling to acknowledge Dieng and Lo’s evidence that the Senegalese government would be “powerless to stop” her relatives, calling the assertion “speculative.” Judge White noted that Dieng and Lo had submitted the State Department’s Senegal 2016 Human Rights Report as evidence to validate their claims. The report states that during the timeframe of its analysis, the government did not intervene to punish those who performed FGM – affecting nearly one-fifth of Senegalese girls – even though Senegal had formally criminalized FGM.

Thapar’s deciding vote didn’t just fail to protect Dieng and her daughters – it robbed them of the universal human right to bodily autonomy, sending a dangerous message to other asylum-seekers in the U.S. who are at risk of similar violations in their home countries.