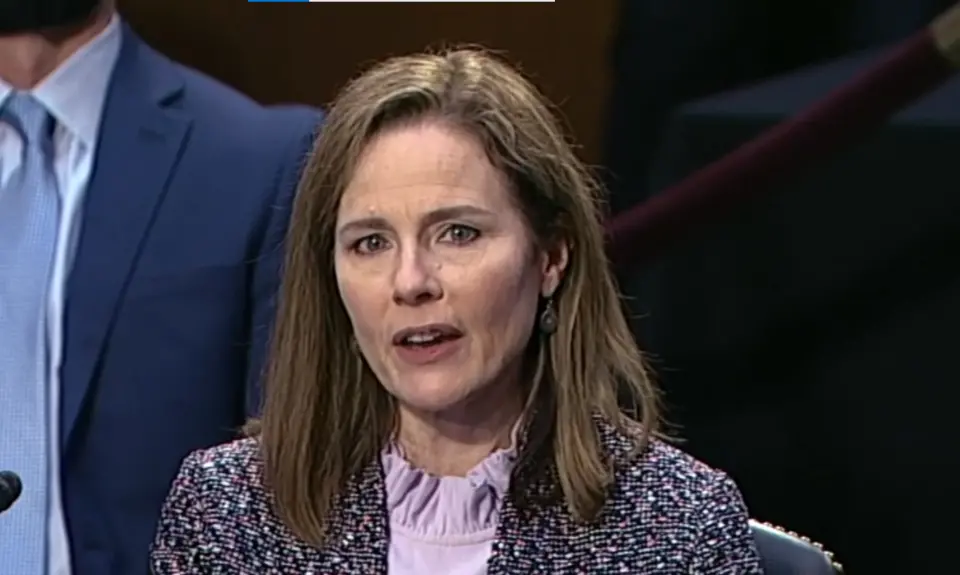

Judge Amy Barrett's hearing testimony and her academic writings give Republicans encouragement as they race to get her onto the Supreme Court in time to hear the Republican challenge to the Affordable Care Act a few days after Election Day. (Our discussion of that case is in our term preview.)

During the second day of her confirmation hearing, Barrett repeatedly tried to assure Democratic senators and Americans concerned about their health care that legal question in the case is unrelated to the one before the Court in NFIB v. Sebelius, the 2012 case upholding the ACA that she is on record as disagreeing with. (That is when Court upheld the individual mandate as a tax but not as an exercise of congressional authority to regulate interstate commerce). She told committee members:

[The current] case involves a very different issue, this issue of severability ... Nothing that I've said with respect to the ACA in print, in my law review articles actually bears on the severability question, so it's not indicative of how I might approach that question.

As an initial matter, her careful phrasing that she has not indicated her position “in print” leaves open the possibility that she has stated her opinion to people in conversation and that those supporting her nomination are well aware of it.

But even putting that aside, there are a couple of problems with her assertion. First, the justices won't even get to the statutory question unless they first buy the ACA opponents' constitutional argument, which is based on NFIB v. Sebelius: that reducing the tax penalty to zero means the law is no longer authorized under Congress's taxing power, and since it is also not within Congress's power under the Constitution's commerce clause, it must be struck down. We already know that she agrees with the dissenters in that case.

Second, her writings on statutory interpretation indicate she might strike down the entire law as “inseverable” from the section she would consider unconstitutional. The ACA opponents argue that the ACA itself makes the entire law stand or fall on the existence of the mandate, citing a congressional finding in the original 2010 act that the mandate is “essential” to creating effective health insurance markets. But ACA defenders point out that Congress made the mandate severable from the rest of the law in 2017 when it reduced the penalty to zero while keeping the rest of the law.

Barrett's comments in a 2019 lecture she titled "Assorted Canards of Contemporary Legal Analysis: Redux” suggest that she may ignore what Congress did in 2017.

[W]hy should we care what the current Congress thinks about a previously enacted statute? Whether you think that what matters is “the language of the statute enacted by Congress,” the intent or purpose behind the enacted statute, or something else, most theories of statutory interpretation seek to give a statute the meaning it had at the time that it was enacted. So what a later Congress thinks is irrelevant.

If Barrett decides it is "irrelevant" that Congress in 2017 showed that it considers the mandate severable from the rest of the ACA, then millions of Americans could lose the protections that law provides, including protections for people with preexisting conditions.